Washington’s coastlines and waterways are at a threshold. Battered by a legion of insults—polluted runoff, shoreline development, carbon-induced acidification, and more—there is no guarantee that the Northwest can continue to support the vibrant natural systems it is known for. The region’s native orcas are struggling; key populations of shellfish and herring may be dying out; and even its flagship species, the salmon, are endangered in many places. And what is perhaps the biggest threat of all looms like a specter: a catastrophic oil spill.

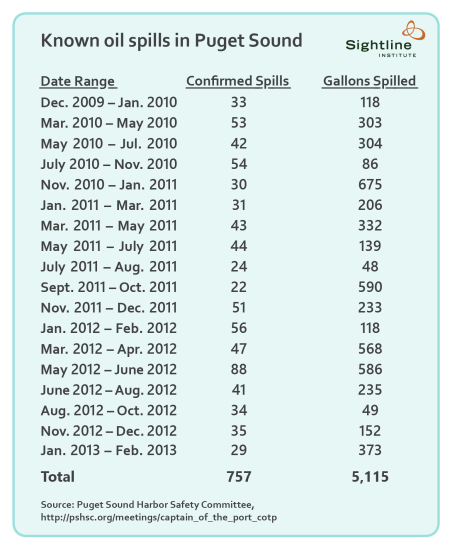

Every day the region faces the risk of an oil spill. Though Washington officials have been more diligent in their preparations than their counterparts elsewhere, there is good reason to believe we are not prepared. In fact, a review of the record shows that our business-as-usual approach has let us down at many times and in many places.

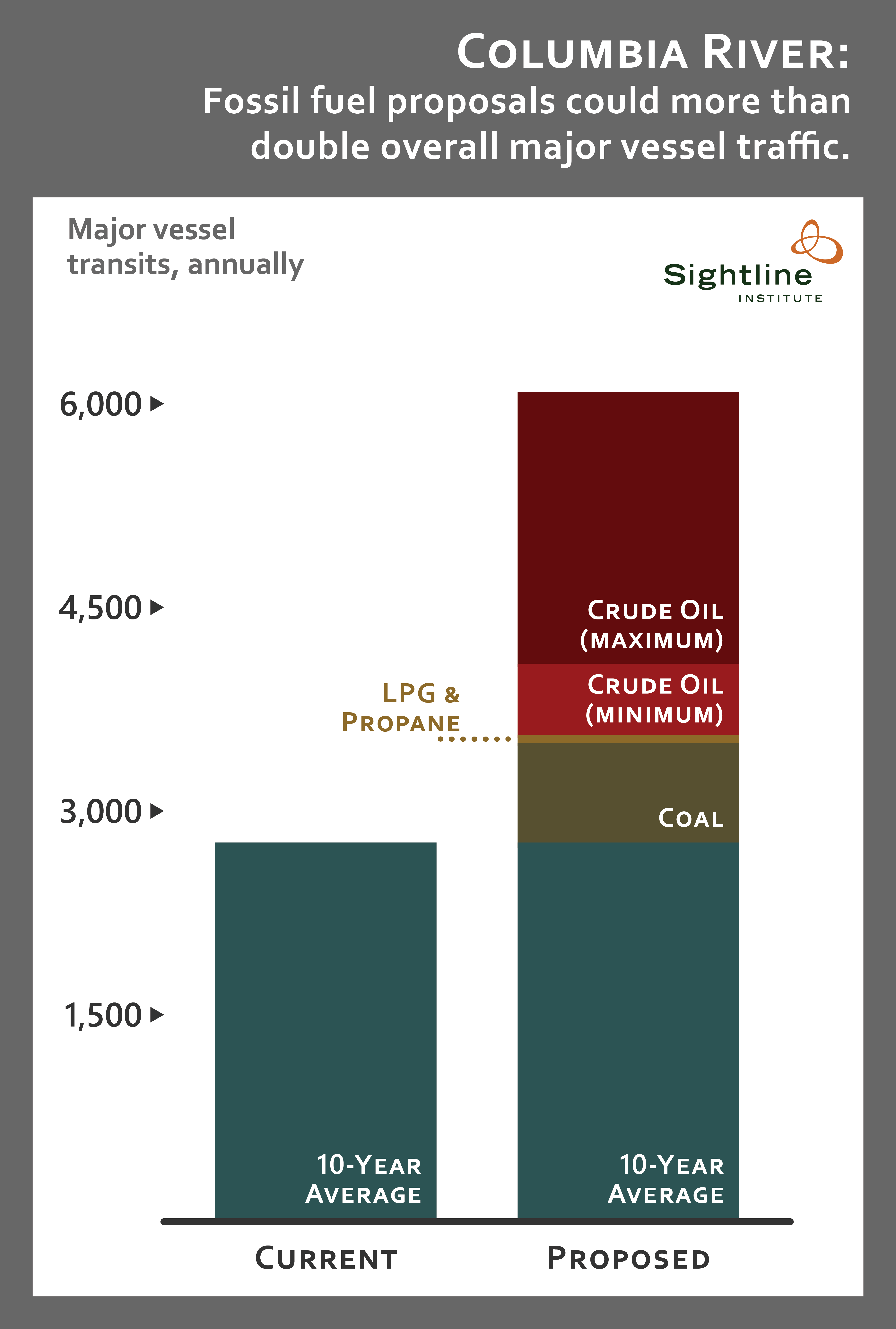

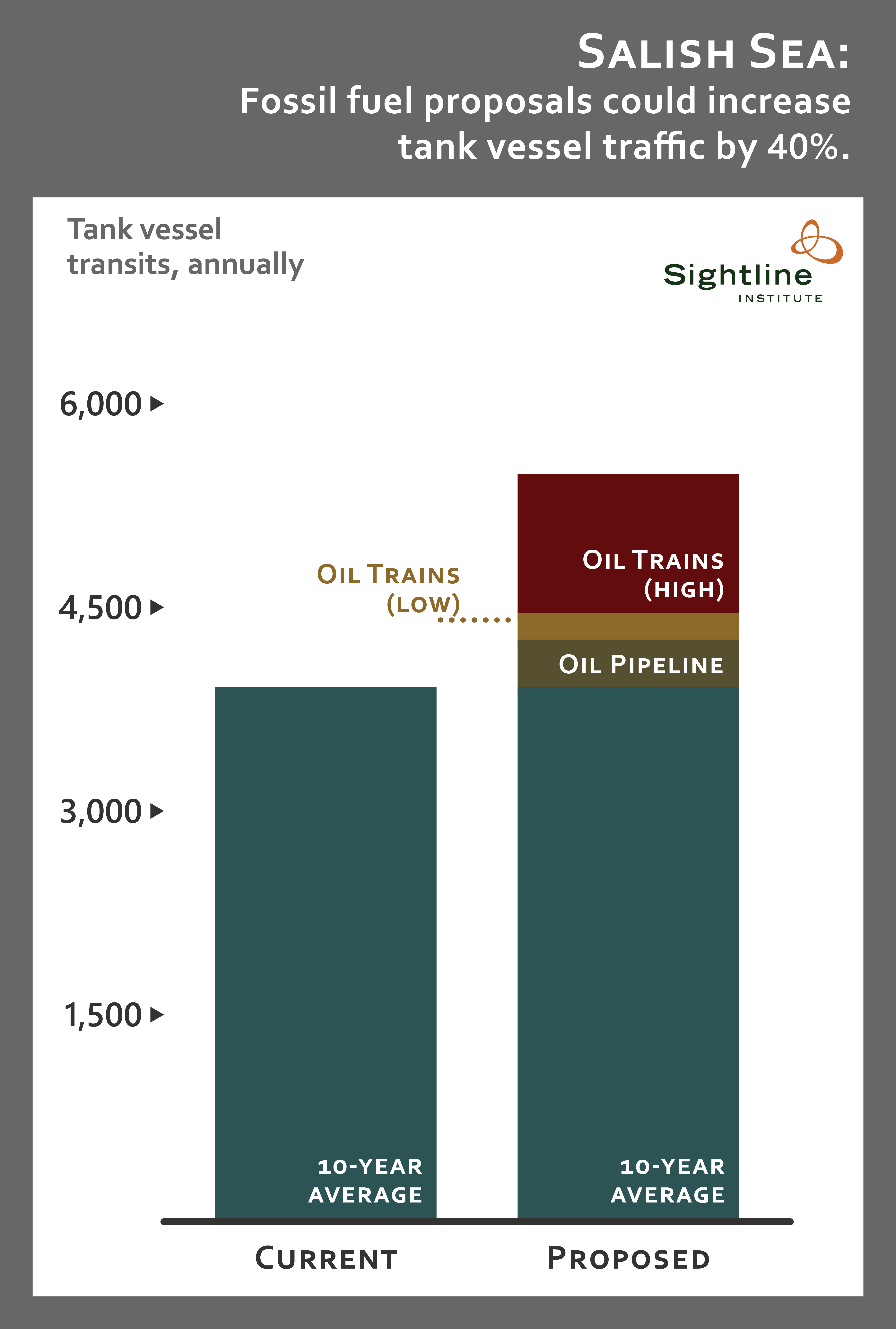

Certainly, we are not up to the task of protecting Northwest waters from the titanic increases in oil transport planned by pipeline companies, refineries, and would-be exporters. To understand why, it helps to recall our history lessons. The fact is that Washington has already suffered numerous damaging spills.

Here are a few of the worst.

Pacific Coast (March 1964)

A tugboat towing a barge loaded with gasoline from the Ferndale refineries was making a delivery run down the outer coast to Coos Bay, Oregon when the tow line ran off its winch drum during a storm in the middle of the night. Set adrift, the 200-foot barge, which was carrying 2,352,000 gallons of gasoline, diesel, and stove oil, soon grounded on a sandbar several hundred yards offshore between Moclips and Pacific Beach, just south of the Quinault Indian Reservation.

Rough surf pounded the stranded barge and stymied the Coast Guard’s initial efforts to pull it free. It took more than five days, and the assistance of another tug dispatched from Grays Harbor, before workers were finally able to move the barge off the bar, but while they struggled 1.2 million gallons of petroleum leaked into the water. The spill fouled beaches from the Quinault Reservation south for 10 miles, killing untold numbers of seabirds. Wildlife researchers also reported massive shellfish deaths: 32,000 pounds of razor clams were killed by the spill, and officials immediately closed clam digging everywhere north of the Copalis River.

In an out-of-court settlement, the United Transportation Company eventually agreed to pay $8,000 in damages—about $61,000 in today’s dollars.

Read more