More than 80 percent of teen pregnancies are accidents. A girl with other hopes and dreams—or maybe a girl who is floundering, who hasn’t even begun to explore her hopes and dreams—finds herself unexpectedly slated for either an abortion or 4,000 diapers. Given the shame and stigma surrounding abortion in many American subcultures, that can seem like a choice between the proverbial rock and hard place. The exciting news that launched this Sightline series is that teen pregnancy is in decline across the United States and across all major ethnic groups. Fewer and fewer young women are facing hard decisions after the fact.

All the same, America continues to have the highest teen pregnancy rate of any developed country, and Canada looks stellar only when compared to the States. Even in Cascadia, which is better off than most regions, several thousand babies are born each year to girls between the ages of 15 and 17, and thousands more to young women aged 18 or 19 (e.g., Oregon 2012, Washington 2012, British Columbia 2010). Across the United States, almost 1,000 infants are born to teens each day. And approximately 30 to 50 percent of teen girls who give birth will experience a rapid repeat pregnancy within 24 months, which multiplies medical complications and the risk of lifelong poverty.

Economic Inequality

Early unplanned childbearing widens the gulf of income inequality. Pregnancy often compels girls to drop out of school, and fewer than 40 percent of those who give birth before graduating go on to complete high school by age 22. In a survey of high school dropouts aged 19–35, only 17 percent held full-time jobs, and half of those employed said they had no opportunity to advance beyond their current position. By age 25, even those who do work full time earn 30 percent less than their peers who completed high school and 60 percent less than college graduates. Their loss of productivity and income has been called a permanent recession.

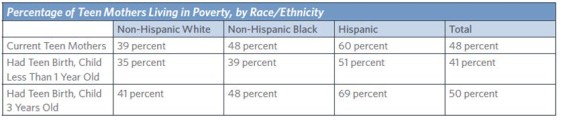

Racial Justice

Early unplanned childbearing also widens racial disparities. Birthrates for black and Hispanic teens are more than double that of their white peers and quadruple the rate for Asian/Pacific Islanders. Since the birthrate is highest among Latinas, some people assume that early childbearing is simply a cultural norm. But a wide-ranging survey of US Hispanics found that Hispanic parents had other dreams for their daughters, and so did the girls who ended up pregnant. In the words of one advocate, Ruthie Flores, “There’s a big disconnect between pregnancy rates and what Latina families want and value.”