Rain garden maintenance has emerged as one of the big hurdles to expanding the use of green stormwater solutions. You build it. The rain comes. Then what?

In some ways, the water-absorbing gardens are not much different than other landscaping features. They need weeding, some summer irrigation, and basic pruning. But they also require more nuanced care.

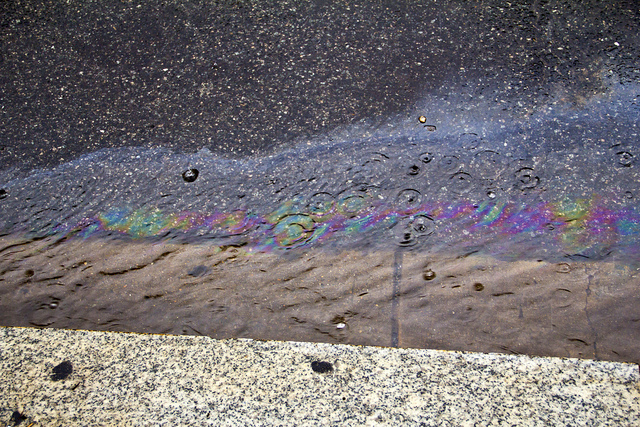

The standard “mow, blow, and go” strategy that sends some commercial landscapers whacking plants and lawns with mowers or hedge trimmers, then revving up the leaf blower to blast the ground clean just won’t cut it. Rain gardens need lusher plantings to catch rain in their leaves and branches and healthy roots to help water soak into the ground. The green infrastructure often features a thicker cover of water-trapping mulch. Good rain garden maintenance means saying ‘no’ to Edward Scissorhands-inspired pruning and bare soil. It requires attention to how the water flows into—and sometimes out of—the garden, and how quickly the water seeps into the ground.

To help solve these maintenance challenges, some smart stormwater folks in Oregon have released “Field Guide: Maintaining Rain Gardens, Swales and Stormwater Planters (2013),” a handy how-to for keeping rain gardens functional as well as beautiful. The guide opens with specific recommendations on what tools you’ll need for rain garden maintenance, gives cautionary notes—and scary photos!—of some of the injury-inducing weeds lurking out there, and provides explicit instructions on how to maintain the gardens’ stormwater treating capacity.