There are plenty of words to describe the ongoing drama over Seattle’s not-boring tunnel boring fiasco. Ironic, for one, given that the 8-inch pipe that brought the world’s largest tunneling machine to a halt was put in Bertha’s way by none other than the Washington State Department of Transportation, as part of the early feasibility studies for the very tunnel they’re now trying to build. Entertaining, because both WSDOT and Seattle Tunneling Partners, the private group that WSDOT hired to dig the tunnel, are busy pointing fingers at one another, positioning themselves for the inevitable battles in court and in the press. Exasperating, too, since it’s becoming increasingly unlikely that the tunnel will be completed on time, on scope, and on budget.

But unexpected? Not in the least.

Sure, nobody foresaw that Bertha would run aground on this particular well casing, any more than they predicted the machine’s “painfully slow start,” or prophesied the specific labor disputes and technical problems that halted work for four weeks in August and September.

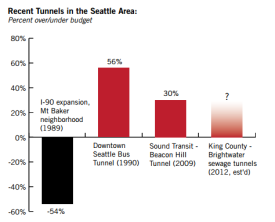

Still, anyone who is surprised that a mindbogglingly complex megaproject like the deep bore tunnel could go badly awry simply wasn’t paying attention. As our 2009 report on Seattle-area cost overruns highlighted, three out of four of greater Seattle’s four major tunneling projects went substantially over budget. And while the I-90 tunnel through Mt. Baker came in well under budget, Seattle’s experience suggests that tunnel troubles are the rule, not the exception.

But it’s not just Seattle. Oxford University researcher Bent Flyvbjerg has documented a worldwide tendency for megaprojects to go over budget.

Translation: the state itself says that in the early years, a tolled deep bore tunnel would carry only about a third as much traffic as the existing Viaduct. The remaining traffic—roughly 72,000 cars and trucks—would be diverted onto I-5 and city streets.

Translation: the state itself says that in the early years, a tolled deep bore tunnel would carry only about a third as much traffic as the existing Viaduct. The remaining traffic—roughly 72,000 cars and trucks—would be diverted onto I-5 and city streets.