Five years ago, many scientists probably thought they’d never see large pools of corrosive water near the ocean’s surface in their lifetimes.

Basic chemistry told them that as the oceans absorbed more carbon dioxide pollution from cars and smokestacks and industrial processes, seawater would become more acidic. Eventually, the oceans could become corrosive enough to kill vulnerable forms of sea life like corals and shellfish and plankton.

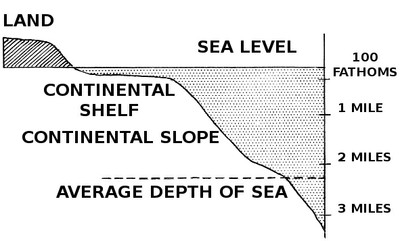

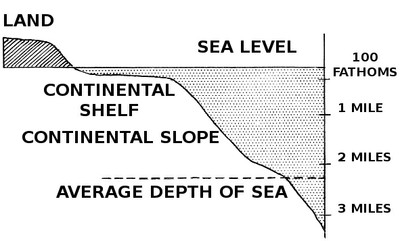

But scientists believed the effects of this chemical process—called ocean acidification—would be confined to deep offshore ocean waters for some time. Models projected it would take decades before corrosive waters reached the shallow continental shelf off the Pacific Coast, where an abundance of sea life lives.

But scientists believed the effects of this chemical process—called ocean acidification—would be confined to deep offshore ocean waters for some time. Models projected it would take decades before corrosive waters reached the shallow continental shelf off the Pacific Coast, where an abundance of sea life lives.

Until a group of oceanographers started hunting for it.

“What we found, of course, was that it was everywhere we looked,” said Richard Feely, an oceanographer at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Pacific Marine Environmental Laboratory in Seattle, who was one of the first to recognize the trouble ahead.

The researchers found surprisingly acidic water—corrosive enough to begin dissolving the shells and skeletal structures of some marine creatures—at relatively shallow depths all along the West Coast, from British Columbia to the tip of Baja California. Researchers hadn’t expected to see that extent of ocean acidification until the middle to the end of this century. But in a seasonal process called “upwelling,” summertime winds pushed surface waters offshore and pulled deeper, more acidic water towards the continental shelf, shorelines, and beaches.

Or, as one Oregon State University marine ecologist put it: “The future of ocean acidification is already here off the Oregon Coast.

Acidifying water poses a threat to marine animals, especially ones that need calcium carbonate to build shells and skeletons. In the Northwest, that includes everything from geoducks, a giant clam that supports one of the region’s most valuable commercial fisheries, to krill, the tiny shrimplike creatures that give salmon flesh its distinctive pink color and feed rockfish, seals, and whales.

Other effects of low pH water on marine creatures range from lethal to bizarre to beneficial. In laboratory studies, clownfish exposed to more acidic seawater have lost their sense of smell and ability to find habitat, Antarctic krill embryos failed to hatch, northern abalone larvae from British Columbia died, squid didn’t want to move, and some eelgrass grew more abundantly.

Then, the oceanographers announced another startling discovery last summer. On the surface of Puget Sound, they found waters with a pH of 7.7, roughly on par with the most acidified waters found in the earlier study along the West Coast. In the deeper waters of southern Hood Canal, the acidity level was even higher—the pH plummeted to 7.4.

Then, the oceanographers announced another startling discovery last summer. On the surface of Puget Sound, they found waters with a pH of 7.7, roughly on par with the most acidified waters found in the earlier study along the West Coast. In the deeper waters of southern Hood Canal, the acidity level was even higher—the pH plummeted to 7.4.

It was some of the most corrosive seawater recorded anywhere on Earth.

Read more

But scientists believed the effects of this chemical process—called

But scientists believed the effects of this chemical process—called  Then, the oceanographers announced

Then, the oceanographers announced  Every day, the oceans do us a huge favor. Across the planet, they absorb nearly

Every day, the oceans do us a huge favor. Across the planet, they absorb nearly  Marine life—from clams to king crab, sea urchins to salmon—has supported the Northwest and its inhabitants for centuries. But a mix of ocean currents and chemistry has put local waters on the

Marine life—from clams to king crab, sea urchins to salmon—has supported the Northwest and its inhabitants for centuries. But a mix of ocean currents and chemistry has put local waters on the  There’s a lot riding on how marine creatures will adapt to acidifying oceans. The animals that dissolve in more corrosive seawater range from

There’s a lot riding on how marine creatures will adapt to acidifying oceans. The animals that dissolve in more corrosive seawater range from