Picture a series of copper beads on a fine titanium alloy wire curved in a graceful sphere. It looks like an earring, but you won’t find it in a jewelry store. It’s made to go in your uterus.

Intrauterine contraceptives are the fastest growing method of birth control in the US. One study showed that use doubled in just two years. Why are IUDs suddenly hot among young women? And what should you tell your friend or daughter when she says she wants one?

Stones in Camels?

The idea of putting something small in the uterus to prevent pregnancy goes way back. When nomadic traders needed to keep a female camel from getting pregnant during long treks across the desert, they put stones into the animal’s uterus. Or so the story goes. When Arab gynecologists hear Europeans repeating this tale, they snort and ask, “Have you ever tried to put a stone in a camel’s uterus?” Since the time that a sun-beaten trader might have contemplated camel contraception, intrauterine birth control has come a long way.

Silver and Gold Pessaries

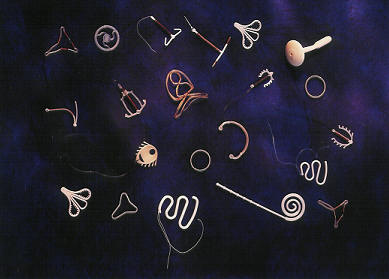

The ancient Greek father of medicine, Hippocrates, is credited with first suggesting small objects in the human uterus to prevent pregnancy. But such a practice would not become common for another two millennia. The precursors of modern IUDs emerged in the late 19th century in the form of “stem pessaries.” The pessary was a curved disk that fit the upper part of the vagina like a cervical cap with the “stem” passing through the cervix to hold it in place. The most elegant designs were made of 14 karat gold and finely crafted, but in the absence of flexible materials, antibiotics, and sterile technique, women who used pessaries risked injury and infection.