An analysis of growth in 15 similar US cities shows that Oregon’s land-use policies excel in protecting rural land.

View the report

A new analysis of growth in 15 similar US cities shows that Oregon’s land-use policies excel in protecting rural land. Person for person in the last decade, new development in metropolitan Portland consumed less than half as much land as the average city in the study. From 1990 to 2000, if greater Portland had sprawled like Charlotte, North Carolina—the city in the study with the worst record—it would have lost an additional 279 square miles of farmland and open space, an area more than twice as large as the city of Portland itself.

“The bottom line is that Oregon’s land use laws have been highly effective at protecting farmland and open space in Portland, which suggests that all Oregon cities are benefiting,” said Clark Williams-Derry, research director of Sightline Institute, the Seattle research center that published the study.

“This report affirms the value of Oregon’s unique land use planning system,” said Ellyn McNeil, co-owner of Heritage Plantations, a Christmas tree farm in Washington County. “Without it, the counties closest to Portland wouldn’t be second and fourth in the state for agriculture sales and farmers like me might be out of business. I hope Oregonians have the insight to oppose Measure 37, which would wreak havoc on our farmland protections.”

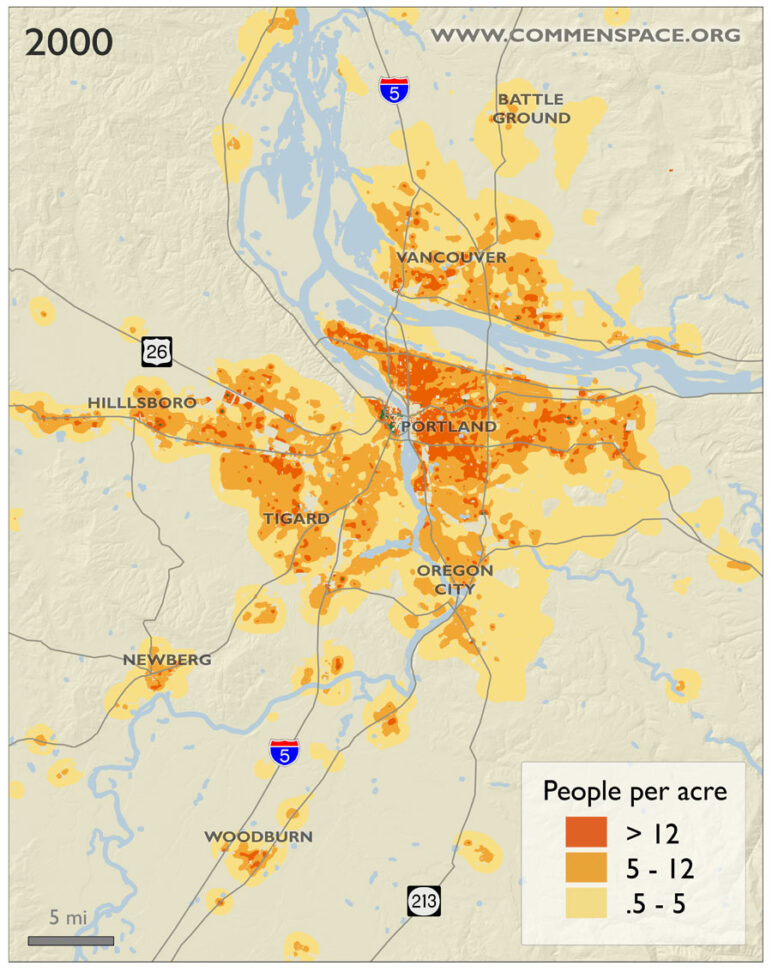

The study, part of the regional monitoring project called the Cascadia Scorecard, used digital mapping of US Census data to track patterns of growth from 1990 to 2000 in the metropolitan areas of 15 cities across the United States with comparable features, including the Northwest cities of Portland, Seattle, and Boise. The Portland metropolitan area analyzed includes seven counties in Oregon—Multnomah, Washington, Clackamas, Marion, Polk, Yamhill, and Columbia—and Clark County in Washington State.

Key findings include:

- Overall, greater Portland ranked third among the 15 cities studied at limiting the loss of rural land and open space in the 1990s, just behind Salt Lake City and Sacramento. (Seattle and Boise ranked eighth and ninth, respectively.) For every 100 new residents added to the greater Portland area between 1990 and 2000, about 10 acres of rural land or open space were converted to housing. In contrast, new residential development in Charlotte, North Carolina-which ranked last-consumed 49 acres of land for every 100 new residents. See Appendix for full rankings.

- Portland ranked first at saving open space among the eight cities in the study that have ample rainfall. Abundant rainfall tends to facilitate sprawl. Between 1990 and 2000, high-rainfall cities in the study consumed about twice as much rural land per new resident as low-rainfall cities such as Las Vegas and Salt Lake City. Portland was the exception. Comparing Portland with the average of other high-rainfall cities in the study, Oregon’s growth policies likely protected 150 square miles of rural land over the decade in greater Portland. (Compared to Seattle, Portland likely protected an additional 88 square miles.)

- Portland ranked first at limiting low-density sprawl. Over the decade, greater Portland added nearly 500,000 residents, yet the number of people living in the lowest-density suburbs (0.5 to 5 people per acre) actually declined. Every other city in this study except Sacramento saw rising numbers of people in low-density sprawl.

The report attributes the city’s record to effective growth planning. “While other western cities have had to limit sprawl because they are hemmed in by desert,” said Sightline research director Williams-Derry, “Portland has saved rural land by making conscious choices.”

“Oregon land use laws encourage reinvestment in existing neighborhoods and existing property,” said Dick Cooley, Portland real estate investor and former chair of the Portland Planning Commission. “The result is a higher quality of urban life for everyone.”

Still, the city has room for improvement. Despite its success at protecting rural land, greater Portland is less compact than many cities of similar size in the western United States. Among the 15 cities studied, it ranked sixth in average density, behind Las Vegas, Denver, Phoenix, Sacramento, and Salt Lake City. (Seattle ranked ninth and Boise ranked 12th.) And it ranked seventh among the 15 cities in the share of residents living in compact neighborhoods (12 or more people per acre). Only one-fourth of greater Portland’s residents live in compact neighborhoods, while half of residents of greater Las Vegas do.

Note: The 15 cities in the study were Austin, Texas; Boise, Idaho; Charlotte, North Carolina; Denver, Colorado; Las Vegas, Nevada; Madison, Wisconsin; Minneapolis-St. Paul, Minnesota; Nashville, Tennessee; Orlando, Florida; Phoenix, Arizona; Portland, Oregon; Riverside-San Bernardino, California; Sacramento, California; Salt Lake City, Utah; and Seattle, Washington.

Sightline Institute (formerly Northwest Environment Watch) is a Seattle-based nonprofit research and communication center that publishes the Cascadia Scorecard, a regional index of progress that monitors seven key trends, including sprawl, that are shaping the Pacific Northwest.