Introduction to RANKED CHOICE VOTING

Ranked choice voting is gaining in popularity. In November 2021 a record 31 cities in the US used ranked ballots to decide their elections. And in 2022, the state of Alaska joined Maine as the second state to rank candidates in statewide contests.

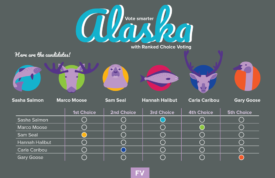

Image by FairVote (Additional resources can be found at https://www.fairvote.org/alaskarcv2020)

Sightline has been writing and researching ranked choice voting for several years. We have found that ranked choice voting improves the incentive structure of elections for both voters and candidates. Voters have more opportunities to vote for the candidates they prefer without having to worry about splitting the vote and causing their preferred party to lose. And candidates and office-holders can more readily rack up wins by forging good working relationships with opponents and catering to the mainstream rather than to a more polarized political base.

So how does ranked choice voting work? Instead of filling in a bubble for just one candidate, voters are free to rank all candidates from most to least favorite. Their top choice is number one, their second favorite is number two, and so on. The candidate with more than half the first-place votes wins. If no candidate has more than 50 percent, the ballots for the candidate in last place are reallocated to voters’ second choices. The process continues until a candidate secures a majority and is declared the winner.

Ranked Choice Voting Explainers

What is Ranked Choice Voting? Score Voting? List Voting? And how do these election structures differ from the current winner-take-all, first-past-the-post voting system?

In this presentation hosted by the League of Women Voters of Portland, Sightline’s former research director Kristin Eberhard explores the way we vote and highlights alternative voting systems in Cascadia and beyond. Examples include Benton County, Oregon, and the state of Maine passing Ranked Choice Voting, a voting system that eliminates the spoiler effect, makes campaigns more positive, and elects candidates who earn true majority support.

US voter turnout is pitifully low compared with other democracies around the world.

Unfortunately, many efforts to boost participation in the United States, but maintain plurality voting methods, yield small returns. For example, get-out-the-vote (GOTV) campaigns to educate, convince, pressure, or scare potential voters into voting are expensive and typically yield only modest results, if any. Single-winner, majority-minority districts that rely on plurality voting can also engage voters, making it easier for targeted minority groups to elect preferred representatives. But, often the positive turnout boost from districting is short–lived. Even automatic voter registration, which noticeably helps boost turnout, doesn’t improve participation to the degree of fair voting methods.

So how do you improve a system that may inherently suppress voter turnout? Instead of making small tweaks to the existing, broken system, a surefire way to convince more people to vote is to make the voting method work for them.

Senator Lisa Murkowski, is the Republican party’s version of a black sheep. She voted against the nomination of Brett Kavanaugh to the Supreme Court, for example, and frequently called out the former president for bad behavior. She is also pro-choice. Though she is a Republican from a red state, many of her supporters are moderates and Democrats. And so Murkowski has become a master of balancing party fidelity with key votes and impassioned statements that make liberals and moderates cheer. Her ability to go even further—demanding a presidential resignation and talking openly about leaving the Republican party—coincides with Alaska voters adopting new open primary and ranked-choice voting systems last November. Alaska’s election reforms grant Murkowski even more freedom to follow her conscience and be pragmatic.

It’s tempting to think of politics in terms of personality problems: if only Obama were warmer, he might be able to break through Congressional gridlock. If only Dino Rossi weren’t such a hard-nose, he wouldn’t inspire such negative campaigns. But with wave after wave of negative campaigns, it seems the problem is not really politicians’ personalities. Maybe all politicians are not bad apples. Maybe our voting system is a bad barrel. The apples are fine when they go in; the barrel itself makes them rot.

Winner-take-all voting spawns negative campaigns. But fair voting—multi-member districts with ranked-choice voting—creates more civil and engaging campaigns.

Where Has Ranked Choice Voting Passed?

In a trailblazing win for election reform, Alaska voters passed an initiative that introduces ranked choice voting to all general elections, starting in 2022. The measure also institutes open top-four primaries and brings more transparency to the identities of donors funding political campaigns.

The success of Ballot Measure 2, also called the “Better Elections Initiative,” puts Alaska in position to become a national model for fixing polarized politics by incentivizing candidates to draw votes from a broader segment of the political spectrum. And it clears the way for Alaskans to support Independents and smaller political parties in general elections without fear of “wasting” their votes.

As Washington lawmakers weigh the “local options bill” this session, Utahns are putting a similar measure into practice. The Beehive State passed a bill in 2018 clearing the path for cities to try ranked-choice voting. Six cities, including the fourth-largest in the state, are already on board and plan to use ranked-choice voting in their 2019 local elections. Utah’s third-largest city is moving toward testing it out in 2021.

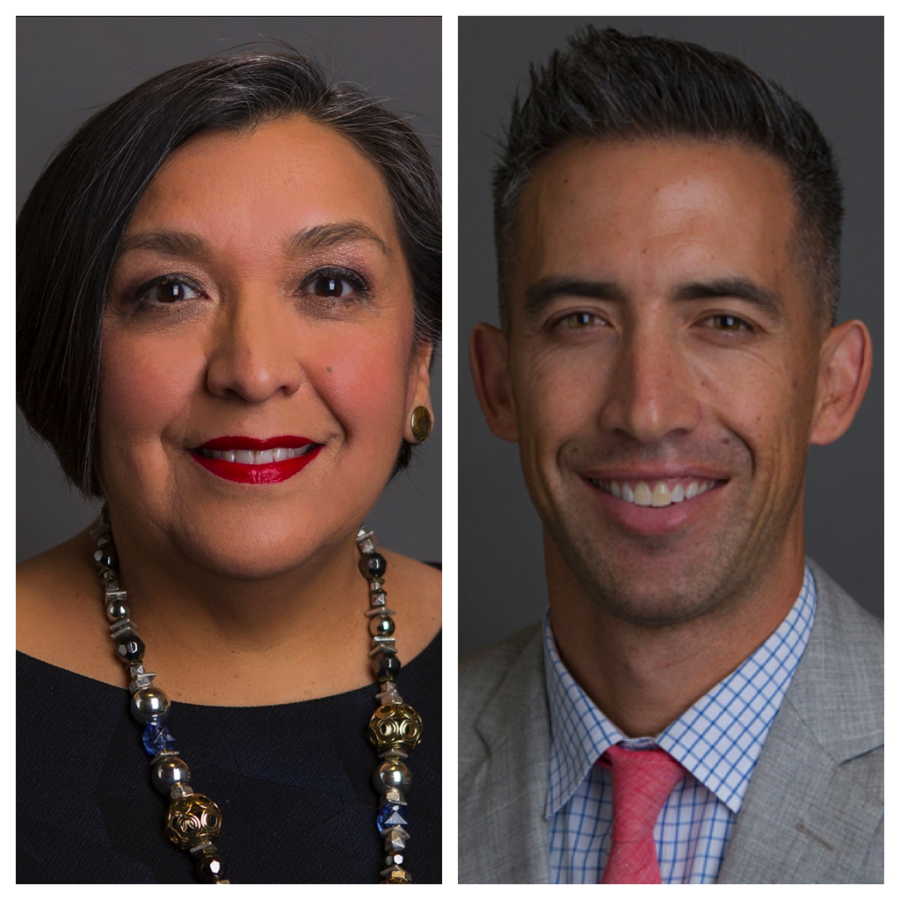

In Utah, a dynamic cross-aisle duo—progressive Democrat Rebecca Chavez-Houck and conservative Republican Marc Roberts—championed ranked-choice voting bills in the house.

Voters in New York City adopted ranked-choice voting for local elections—and the ballot measure didn’t just pass, it won by a landslide, with over 70 percent voting yes! The Big Apple joins 20 other cities around the country that use ranked ballots, including Minneapolis, San Francisco, Oakland, Cambridge, and Santa Fe. Maine is the first state to adopt ranked-choice voting for federal elections. As the US’s most populous city and top economic and cultural center, NYC may prove the most visible success story yet, going a long way to familiarize people across the country with fair voting systems. New Yorkers are likely to experience, as voters in Maine and in other cities have, more positive campaigns and more representative winners.

For more than a decade, Oregon state Representative Dan Rayfield, D-Corvallis, has been advocating for ranked choice voting in Benton County. So it was stirring for him when he finally got to rank candidates on his own ballot for the November general election.

“That’s the culmination of the journey,” Rayfield said. “It is extremely fulfilling when you get to that moment. There’s nothing like that.”

Benton County voters in 2016 passed a measure that implemented ranked choice voting for county commissioner races. That measure took effect for the first time this year—allowing third-party candidates from the Pacific Green Party and Libertarian Party to compete on the ballot without serving as spoilers. Rayfield and attorney Blair Bobier co-petitioned for the measure then, and said the county provided a local example of what ranked choice voting could look like in Oregon.

Future scenarios for ranked choice voting

Community groups in Alaska working to educate voters face a daunting, but doable, task in 2022. For the first time, Alaskans will use top-four open primaries and ranked choice voting to pick the winners in statewide races. Hundreds of thousands of voters across this vast state will need guidance on the new ways of choosing candidates. Turnout and results will hinge on the quality of the information they’re given. If enough Alaskans like the process, other states may decide to unlock the same opportunities for their voters and strengthen the trust and consensus required for a functional democracy.

Public resources for voter education likely won’t be enough. The Alaska Division of Elections will be a valuable hub of information, but its budget is simply too small to adequately prime every voter for the changes ahead. Nonprofits of all stripes, business groups, neighborhood associations, and others can, and should, help by informing their networks and members about how the new system will work. The political returns could be well worth it for groups that support specific causes or candidates. That’s because voters who are familiar with the new ballots will be far more likely to cast one successfully. Organizations can also generate goodwill for themselves by providing trustworthy information on effective civic engagement. They shouldn’t let lack of experience in voter education hold them back.

After four years of Portland Mayor Ted Wheeler, most of the city’s voters were ready to find someone else to take his place. So how did Wheeler win a second term? It was a three-way race. He won fewer than half the votes, but more votes than either of the other two (mostly further left) candidates. If they’d used ranked choice voting, would Portlanders have elected a new mayor?

Wheeler’s prospects for reelection were questionable given his dropping popularity. A DHM poll released in October showed he was behind his biggest challenger, Sarah Iannarone, by 11 percentage points. Another September poll showed nearly two out of three voters thought unfavorably of the mayor. The poll, conducted by FM3 Research and commissioned by a political action committee pushing for community police oversight, also showed strong support for the Black Lives Matter movement and the demand to reverse rising homelessness in the city—both issues at the top of Iannarone’s policy proposals as a progressive candidate.

In 2017, Seattle, Washington, and St. Paul, Minnesota, are both electing new mayors from crowded fields of candidates. Seattle saw a fierce fight leading up to the top-two primary in August and now general election voters will choose between just two candidates on the November ballot. St. Paul has no primary and instead lets voters rank the candidates in the general election race. Voters in St. Paul will rank ten candidates on the November ballot, and their rankings will allow the vote-counting machines to simulate a primary and runoffs to narrow the field until one candidate wins with a majority of participating votes.

Seattleites are gathering signatures for a ballot initiative to amend Seattle’s charter to use ranked choice voting (RCV), like St. Paul and a dozen other American cities. Minnesota allowed Minneapolis and St. Paul to modernize their city elections, but unfortunately, Washington state law prohibits Seattle and other charter cities from doing the same. To comply with state law, the Seattle initiative calls for ranked ballots to select the top two in the primary, rather than eliminating the primary as St. Paul did. But the the proposed charter amendment also includes a provision that would automatically eliminate the city’s primary and switch to ranked voting in the general election if state law changes to allow it.

How has RCV shaped the the mayoral race in St. Paul compared with Seattle?

Here at Sightline, we’re fans of proportional representation, including multi-winner ranked-choice voting. We recently conducted focus groups to find out what voters in Oregon and Washington think about proportional representation. (Sightline director of strategic communications Anna Fahey will write more about these focus groups soon.) Overall, we found out that voters across the ideological spectrum:

1) think we need to change our broken systems,

2) like the idea of proportional representation, but

3) don’t like the methods for getting there.