The claim comes again and again like clockwork: That allowing homes to exist can be hazardous to a politician’s career.

Even at the annual picnic of her own neighborhood association, surrounded by pasta salad and barbeque, Jessica Bateman couldn’t escape the threat.

It was summer 2019. In her first term as a city councilor in Olympia, Washington, Bateman had led a charge to legalize duplexes, fourplexes, and other small apartment buildings in much more of the city. A man who lived down the street from her confronted her about it at the picnic.

“I said, ‘I think people are gonna like it,'” Bateman recalled. “And he said, ‘Or we’re just gonna vote you out of office!'”

Part of his prediction came true: Bateman drew a challenger who made the seemingly controversial new zoning code her central issue. And then Bateman defeated her by 33 points, carrying every precinct in the city.

It’d be hard to call Bateman’s election victory a fluke—or Bateman’s subsequent election to the state House of Representatives and, last week, to the state Senate. Last week’s results offer the latest evidence that in election after election, including last week’s, politicians who support housing options like duplexes, townhomes, and apartments overwhelmingly tend to win their races.

In Washington, universal re-election for pro-housing legislators

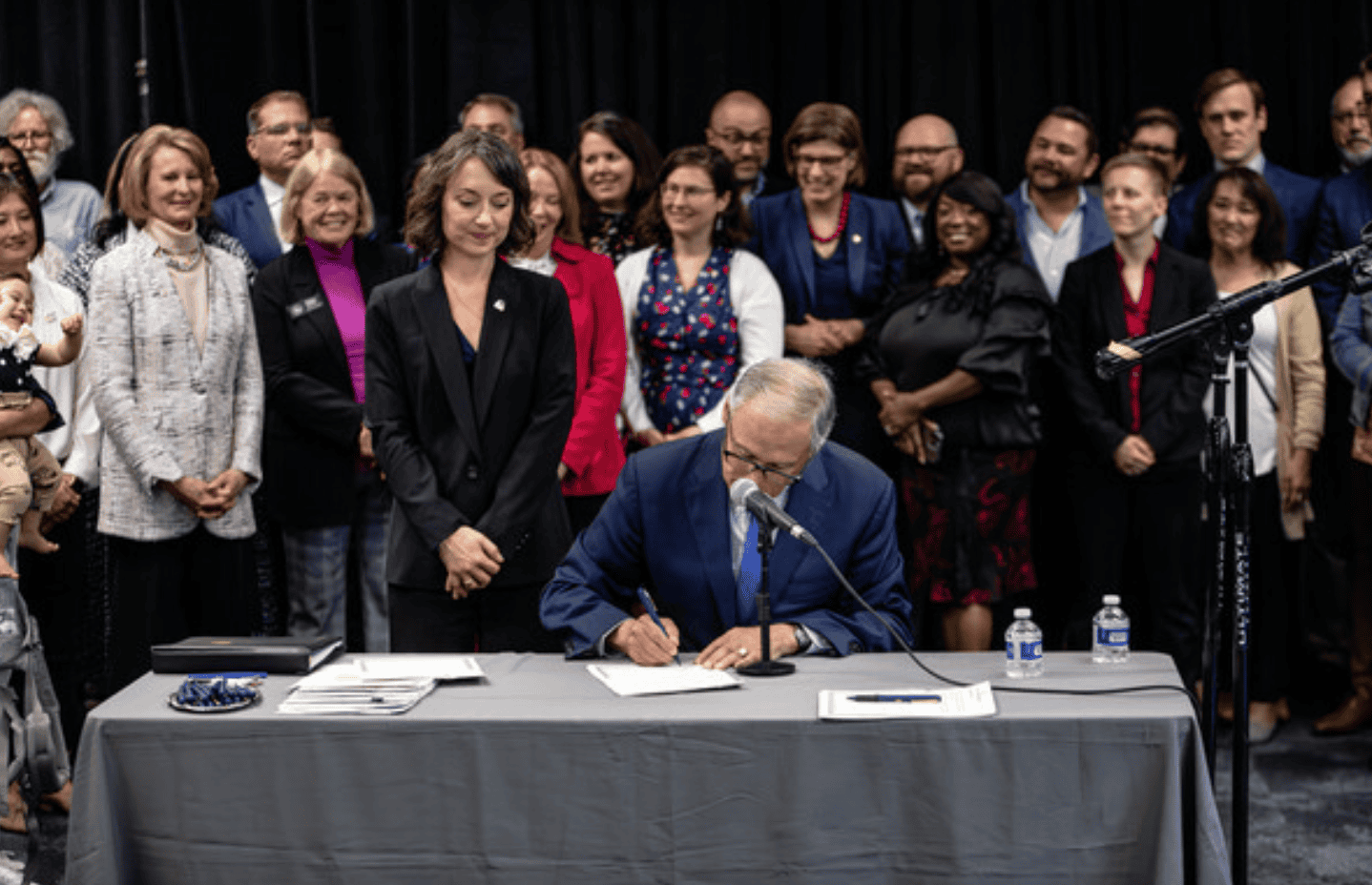

Let’s start with Washington, where Bateman quickly established herself as one of the state’s leading housing advocates after her constituents sent her to the state Capitol. In 2023, she carried a law through the legislature that re-legalized so-called “missing middle” housing, like triplexes and townhomes, in cities across the state.

In a 2022 news report, the state’s largest public radio station had called an earlier version of the concept “potentially career-ending.” Now, 19 months after the contested legislative vote, we can test that notion:

Every single Washington legislator of either party who voted for Bateman’s zoning bill and ran for re-election in 2024 ended up winning both their August primary and November general elections. Six other legislators, including Bateman, ran for new offices and won.

Meanwhile, only three legislators who had supported House Bill 1110 lost, all three after deciding to enter already-crowded races for higher office: Republican Jacquelin Maycumber, who ran for Congress and lost to Spokane County Treasurer Michael Baumgartner; Democrat Kevin Van De Wege, who ran for public lands commissioner and lost to King County Council member Dave Upthegrove; and Democrat Mark Mullet, who ran for governor and lost to Attorney General Bob Ferguson.

In Oregon, zoning reformers in both parties have been defeated only by other zoning reformers

Because Washington’s bill was only passed last year, 18 of its supporters in the state senate haven’t come up for reelection yet. So for a look at the longer-term political implications of a housing bill, let’s check in on Oregon’s very similar fourplex legalization from 2019. Every legislator who voted for that bill, House Bill 2001, has now been up for re-election at least once; House members have been up twice.

Five years later, fourplex supporters in Oregon continue to have a flawless electoral performance:

Out of 48 Oregon legislators who supported HB 2001 and subsequently ran again, only three have lost:

- Republican Sen. Denyc Boles, who’d been appointed to fill a Democratic-leaning seat in Salem and lost to Congregational minister Deb Patterson, a Democrat who went on to co-sponsor a follow-up to the fourplex bill.

- Republican Rep. Cheri Helt, who had won a Democratic-leaning seat in Bend after her opponent faced a sexual abuse scandal. Helt was then ousted after one term in favor of Jason Kropf, a Democrat who also went on to co-sponsor the follow-up fourplex bill.

- Democratic Sen. Betsy Johnson, who ran for governor as an independent and was defeated by Tina Kotek—the author and lead sponsor of HB 2001. (The third candidate in the race, Republican Christine Drazan, had opposed HB 2001 and made it a minor issue in her race against Kotek. Kotek also defeated Drazan.)

In other words, the only fourplex supporters in Oregon who lost subsequent elections were defeated by other fourplex supporters.

In Montana, 84 percent of duplex supporters won their next race—the same as the overall ratio

One other Cascadian state legalized a form of “missing middle” housing in 2024: Montana.

Montana had a more volatile political landscape in 2024, with a major redistricting forcing various incumbents into contested primaries, term limits sending legislators into new races, and Democrats clawing back a few seats after drubbings in 2020 and 2022. But even in that environment, supporters of Montana’s most contested zoning bill of 2023 were overwhelmingly re-elected:

Senate Bill 323, which legalized duplexes in Montana cities with populations over 5,000, passed with large bipartisan majorities, like the other bills in Montana’s cluster of major housing reforms in 2023. But its margins were tighter than the others, so we’ll use it as our litmus test.

SB 323 saw 67 of its supporters run for office in 2024. Of those, 60 either won (including for higher office) or in a few cases were defeated in races against other supporters of SB 323. Their overall loss rate was 16 percent—the same as the overall rate for Montana state legislators in 2024. (For example, two opponents of SB 323 were defeated by supporters of SB 323.)

That said, SB 323 had the worst electoral record of Cascadia’s three state legalizations of missing middle housing: seven of its supporters lost re-election races, all but one via primary. Only one of those seven lost to someone who had voted against the bill.

Polls consistently show a broad majority quietly supports more housing choices

Do pro-housing politicians win because of their support for these measures? It’s impossible to say how much they may have helped—though Kotek’s many newspaper endorsements in her closely fought governor’s race consistently singled out for praise her authorship of Oregon’s fourplex bill.

What seems clearer is that supporting these measures didn’t hurt. And this is consistent with what polls tend to find about zoning reforms and other legislation that removes barriers to homes of all shapes and sizes in all neighborhoods. Allowing housing is more popular than not:

But most people don’t follow the issue closely. That’s what political scientist Clayton Nall found in a paper he co-authored and was published last April in the Journal of Political Institutions and Political Economy. A national quota-sampled poll of residents of urban and suburban ZIP codes found that though people care a lot about housing costs—which is to say, they care about real outcomes—few voters have strong feelings either way about zoning.

“A hypothetical candidate’s position on market-rate housing development (infill or sprawl) was an extremely low-salience issue,” Nall, of the University of California at Santa Barbara, wrote in an email this week.

But if that’s true, why do so many people get the initial impression that legalizing housing is both controversial and toxic? Other research has an answer: there truly is a small, loud minority of people who strongly oppose more homes near them.

“On the issue of housing, those who attend and speak at public meetings tend to have much less positive views of allowing more housing than do their communities overall,” Alex Horowitz and Tushar Kansal of the Pew Charitable Trusts wrote last year.

A 2022 case study from Auburn, Maine, tells the story in a nutshell. Researchers Salim Furth and Eric Cousens documented that at the final public hearing, 11 of 12 testifiers opposed allowing more homes within city limits. But on an online survey with 151 responses, 63% had supported allowing more homes. And in the actual election following the city’s decision to upzone, voters overwhelmingly re-elected the pro-housing mayor and supported a council majority that backed the high-profile changes.

Voters care about whether their leaders are making things better

Alana Moore, 26, and Reilly Elliot, 27, are buying their first home thanks to Oregon’s recent legalization of townhomes on most residential lots. Photo: Michael Andersen for Sightline Institute.

Bateman said that even before the neighborhood picnic confrontation during her early city council campaign, she’d gotten a sense of this dynamic. Yes, a few people seemed dead-set opposed to having less expensive housing options in their neighborhoods. But voters tended to care mostly about housing prices. And Bateman could tell a story about what she was doing to improve housing affordability.

“It’s so relatable: everyone needs a home,” she said. “When they see housing as something they can be a beneficiary of, as something that can help their loved one or their child, they can see the benefit. … In all the thousands of doors I knocked on, I only had one person who got really angry at me, and that was what told me we’re on the right track.”

“That was in 2019,” the senator-elect said. “And since then, we’ve continued to see candidates who ran on pro-housing platforms be successful and be warmly received by the voters.”

Down in Oregon, another politician re-elected last week was state Sen. Lew Frederick. A key swing vote in favor of Oregon’s 2019 fourplex bill during his first senate term, Frederick was easily re-elected in 2020 and went on to co-sponsor its 2021 follow-up.

On Sunday morning, standing in the middle of Frederick’s district outside the new townhouse she’d just agreed to buy, Alana Moore said she hadn’t heard about any of that. In fact, Moore wasn’t aware that until a few years ago, it would have been illegal for her new home to exist.

But Moore, 26, and her fiancé Reilly Elliot, 27, said they were glad that their home is legal now.

Sharing a backyard patio with several other households is “the only way we could have afforded it,” Moore said, and also “honestly, part of the draw.”

“I can empathize with people who might think it’s not a good thing,” she said. “But I feel like with the general lack of community in the entire country right now, this has so many benefits.”