News is news. And fire is fire. But coverage of wildfires in 2024 is more than a matter of acres burned, percentage contained, drought and wind conditions, evacuation orders, and threats to lives and property. All that is important, but it’s not the full story. Journalists play a vital role in interpreting the significance of wildfire events within a broader context. For example, over the past decade, following the available science, reporters have shifted from covering wildfires simply as natural disasters and zeroing in only on a singular “cause” or spark. They are more often clarifying how wildfires are climate-boosted natural disasters, with global warming as one major factor creating conditions for more severe fires that are more difficult to fight.

As science, conditions, and understanding evolves, it’s time to go further. As megafires burn across the west and firefighters put their lives on the line over and over, the news media have an important role to play, highlighting other human-caused factors that exacerbate the wildfire crisis—namely policies that put people and property in harm’s way by encouraging building houses in wildfire-prone areas, lack of information and mandates for fire hardening, and a default tendency to frame all wildfire as simply “bad,” overlooking the use “beneficial” fire as an effective prevention measure.

Here are four ways that journalists can tell the full story of wildfires.

#1: Reframe wildfires as natural

Although wildfires can bring tragic destruction, at the same time, it’s crucial to understand that wildfires and human-started fires have burned regularly throughout the West for thousands of years and that fire has benefits in ecosystem health and in preventing the largest and most severe fires. In places with high summer temperatures, low humidity, and little rain, the natural “fire return interval” can be just 10 to 15 years before another fire comes through, clearing out the debris that would otherwise accumulate into highly flammable kindling and reinvigorating “fire-adapted” ecosystems where fire is needed to activate seeds and clear openings where wildlife can then browse on young tree shoots and ground-level shrubs.

Historic fire frequency, 1650 to 1850. Source: Daniel Dey, Richard Guyette, and Michael Stambaugh.

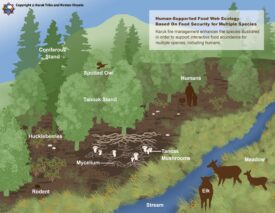

Indigenous people have relied on intentional burns to cultivate food, fiber, and forage and to mitigate big destructive fires. Settler-colonial history of putting out all fires has left a legacy of choked forests where wildlife suffers, and the accumulation of forest fuels turns what could be small fires into megafires.

Now the United States and Canada are transitioning away from full suppression and trying to return a more natural regime of beneficial fire. Their success depends in part on a cultural redefinition of wildfires as a natural occurrence.

Journalists play an important role in redefining wildfires. While wildfire coverage is often necessarily focused on people and property destruction, reporters can begin to recast fires as a natural part of western landscapes. For example, when covering a fire, journalists can:

- Mention the area’s natural fire return interval by referencing a map or noting the area’s level of wildfire hazard. (This is also shown on maps.) Showcasing physical evidence, such as a photograph of fire scars on a cross-section of tree growth rings, is also effective. This sets the expectation of fire as a natural occurrence with an important role in preventing the accumulation of fuel.

- Show that fire is baked into ecosystem life by referencing local species that are fire-dependent or fire-adapted. Journalists can identify such species with the help of the US Forest Service, US Bureau of Land Management, or state department of natural resources.

- Describe wildfire in neutral terms instead of alarming and negative ones. For example, use “large and high–intensity wildfires” or just “wildfires” instead of “raging” or “devastating wildfires.”

- Measure damage in terms of community destruction rather than acres burned. For example, instead of “2024 has been Oregon’s worst fire season ever,” remove the judgment and write “while more acres have burned in 2024 than in any fire season on record in Oregon, few structures have been lost.”

Burn scars show the history of fire frequency before the start of fire suppression. Source: National Park Service; Alan Taylor, Pennsylvania State University

#2: Report on the beneficial aspects of wildland fires

When fires leave destruction in their wake, that destruction becomes the main news story. But the untold wildfire story is that most wildfires do not destroy human-made property. Further hidden is the fact that wildfires tend to improve forest health and that small low-intensity fires mean fewer high-intensity, destructive wildfires as well as less smoke and more carbon storage in fire-adapted ecosystems.

Press coverage and education on these important jobs that wildfire performs would lay the groundwork for policies and practices that deliver more “beneficial fire.” Two important tools to realize these benefits are prescribed burns and what firefighters call “managed wildfire for resource benefit” (MWRB), the clunky term of art for carefully monitoring a wildfire as it is allowed to burn and restore forest health instead of immediately and completely putting it out. Reporting on these practices can illustrate their community upsides, such as reducing public spending on future emergency fire suppression. Here are ways that journalists can show the benefits of fire:

- Discuss the specific forest health benefits of wildfires. During the decades after a wildfire, report on the resulting forest health and ecological richness.

- Note the community safety benefits of wildfire. For example, document when a current fire stops or becomes less severe when it reaches the perimeter of a past fire that has cleared out forest fuels.

- Cover prescribed burns. Highlight that for the rare controlled burn that escapes, many valuable burns take place. (Steal this title: “Firefighters use controlled fire to fight out-of-control fire’s toll.”)

- Give examples of the tangible, broadly experienced benefits of controlled preventative burns, such as air quality. (A little smoke now is less harmful than a lot of smoke later.)

- Report on firefighters’ efforts to monitor and manage wildfires for the benefits they may provide instead of immediately and completely suppressing them. (This includes allowing a fire to burn in a direction where it does not threaten communities while using total suppression on a community-facing front.) Use, for example, information such as this from the National Wildfire Coordinating Center: On July 8, 73 large active fires are being managed nationwide and have burned 499,192 acres. Of these, 48 wildfires are being managed under a strategy other than full suppression because of the forest health benefits fire may provide. Even when the news is that a fire has been immediately and fully suppressed, reporters can help people understand managed wildfire, as in this hypothetical example: “Because the fire is too close to residential areas, no part of it is being managed for resource benefits; the strategy is immediate and full suppression.”

#3: Point out that residences in hazard areas are a main factor in structure loss and wildfire spending

It is crucial to not blame victims for wildfire tragedy. At the same time, it is vital to identify what is emerging as a primary cause of wildfire destruction: building houses in fire-prone areas of the wildland-urban interface (WUI). This is as important as (and more controllable than) the two more commonly cited factors escalating the wildfire crisis: climate change and the buildup of forest fuels. Housing developments are spreading at an alarming rate in the fire-prone WUI, often in the footprint of a recent fire, and this significantly raises the number of fires, property damage, and public spending on fire suppression. Development in fire-prone areas also hinders the effective use of tools such as prescribed burn and managed wildfire for resource benefit (MWRB).

Here are some ways that journalists can build this context into wildfire coverage:

- Along with climate change and forest fuels, highlight residential development in natural fire areas as a major factor driving the wildfire crisis.

- When wildfires threaten new dwellings that were constructed despite clear wildfire risk, point this out and report on the additional public spending on fire resources.

- When reporting on evacuations or structure loss, include research that links residential development patterns to wildfire damage.

- Cite the higher suppression costs and greater danger to firefighters when houses are near wildlands.

#4: Report on policies, including financial incentives, driving housing development decisions

Follow the money. Whether it’s public subsidy for firefighting, insurance industry practices, or land use laws, public policies are driving patterns of wildfire destruction. Specifically, these policies incentivize two primary causes of wildfire destruction: building new houses in high-hazard zones and not fire-hardening at-risk homes. Voters could change these policies that exacerbate the wildfire crisis and strain public coffers—if they knew about them.

One key reason homeowners build in risky places and neglect to fire-harden is that they do not bear anywhere near the full costs of preventing, fighting, or recovering from wildfires. Without fire protection, homes in hazard areas, especially non-hardened homes, would burn down. Fire protection alone can subsidize up to 20 percent or more of a home’s value in the western United States. When this fire protection fails, the public costs of emergency response, infrastructure repair, and debris removal add additional hidden subsidies to private homeowners, amounting to billions of dollars annually. In addition to these taxpayer-funded subsidies, private home insurance customers across the United States, especially those in low-hazard areas, are subsidizing insurance premiums in high-wildfire hazard zones.

If people had to pay the full cost of wildfire insurance, they would be more likely to build less and fire-harden more in the fire-prone WUI.

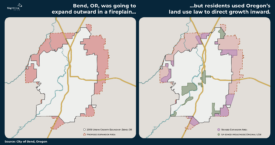

Urban land use policies are another hidden driver of housing growth in fire-prone places. Restrictions that prevent homebuilding in established cities and towns, such as single-detached zoning and minimum parking mandates, drive housing availability down and prices up. These rules push new housing development to sprawl and incentivize building in the WUI. When we talk about wildfire risk to people and homes, we should look at laws in nearby jurisdictions that are pushing new housing (and the people who need it) away from wildfire-safe cities and towns and into harm’s way.

Here are some points that journalists can raise:

- When reporting on the public costs of fighting and cleaning up after wildfires, connect skyrocketing public expenditures to the incentive that “free” fire services offer for building new dwellings in wildfire-hazard zones.

- Explain that insurance nonrenewals and rate increases should be vital indicators of where it is unsafe to build. But emphasize that today’s artificially low premiums (due to low-risk customers subsidizing premiums in wildfire zones and premiums not reflecting ever-intensifying wildfires) are sending the wrong message and encouraging people to build in harm’s way.

- When legislatures are considering passing or rejecting urban pro-housing legislation, such as allowing more housing near transit, legalizing co-living homes, easing parking mandates, and relaxing single-detached housing restrictions, discuss the consequences for rural sprawl and wildfire risk (and the related hidden costs for everyone).

- Report on proactive measures to redirect growth away from wildfire hazard areas.

- Report on proactive measures to spur fire hardening.

- Highlight places where land use/growth management laws and ordinances are successfully preventing wildfire damage by limiting growth in fire-prone areas and encouraging infill housing in existing urbanized areas (e.g., Bend, Oregon).

Journalists can modernize wildfire beliefs

Our expectations regarding wildfires have rapidly evolved. For much of the twentieth century, firefighting could protect communities, and the conventional wisdom has been that wildfires are bad. But today, even the best technology cannot always control climate-intensifying wildfires, and the costs and risks of protecting populations in fire-prone areas are mounting, with climate change supercharging wildfire severity and populations sprawling into natural wildfire landscapes. Now the scientific consensus is that fire can play a beneficial role in fire-adapted landscapes by helping to prevent crisis-level destruction, health impacts from smoke, and loss of human life, livestock, and property. Policies are finally starting to shift toward reallocating funds from fire suppression to prescribed burns and encouraging fire-adapted communities.

However, public awareness is still lagging. Many people still do not realize that allowing some fires to burn can prevent larger ones or that a little smoke now means less smoke later. Even fewer people recognize that publicly funded firefighting, urban housing policy, subsidizing insurance, and insufficient growth management can inadvertently encourage risky development in fire-prone areas. Journalists can bridge this knowledge gap by providing essential context about the policies that are driving up the costs of wildfires and making all of us vulnerable.

Rich Fairbanks

In my experience the single largest problem with fire journalism is how they treat controlled burns. When a spring burn goes 100 feet outside the fireline and barely scorches a few shrubs, the headline is “Authorities Lose Burn, Start Wildfire,” subhead “Lazy Federal Bureaucrats Screw Up Again.” It is inaccurate and it is fear mongering in a way that is destructive to our forests and encourages ignorance.