It’s hard to imagine a building more compatible with Oregon Governor Tina Kotek’s stated goals than the Owens II Apartments.

A four-story apartment building that’d sit next to another four-story apartment building in central Astoria, the proposed mixed-income project would be priced entirely for low-income and very-low-income seniors thanks to millions of dollars in federal subsidy that have already been lined up. Sitting in the walkable core of a small city where home prices are up 48 percent in the last four years, the 50 new homes would replace a mostly empty parking lot.

However, the site is directly downhill from three Airbnb rental units that describe themselves as “riverview” and charge $181 a night for the chance to watch cargo ships humming up and down the Columbia River, just across that mostly empty parking lot.

In public hearings and legal filings for more than a year now, the owners of those Airbnbs and another family that owns a house across the street have raised first one issue about the proposed apartment building, then another. It’s been a very expensive game of chicken for the dueling lawyers hired by the site’s neighbors and the Northwest Oregon Housing Authority, which wants to build those 50 homes. Regardless of how this legal battle ends, the delay has postponed the project and could end up killing it.

In short, the Owens II Apartments would be exactly the sort of building Gov. Kotek seems to want to dedicate much of her governorship to helping create. So why, after more than a year of policy development, will Kotek’s top-priority housing bill do so little to help it—and thousands of other potential buildings like it—get built?

50,000 missing apartments in Oregon

To be clear, Gov. Kotek’s Senate Bill 1537, which passed the state legislature Monday, might help the Astoria project claw its way over the finish line and provide permanently stable homes to 50 low-income senior-led households in northwest Oregon. One notable provision of the bill: if the people trying to stop the project lose their legal argument, the new law could eventually require them to pay attorneys’ fees for both sides.

But that outcome is not certain, and would come only after a long and risky legal battle.

A different section of SB 1537, the subject of much quiet debate within Oregon’s government over the last year, might have been a much bigger help. An earlier version would have automatically approved requests by housing developers for exceptions, or “adjustments,” to various zoning rules. For their Astoria project, the Northwest Oregon Housing Authority would have automatically been allowed to build a much smaller parking lot, avoiding the need for excavation that’s become the latest focus of the legal battle.

But during the lead-up to Oregon’s 2024 legislative session, that section of Kotek’s bill was largely gutted in the face of opposition by various Oregon cities.

Subsidized housing like the Owens II aren’t the only homes at stake. Gov. Kotek has set a high-profile goal of accelerating the state homebuilding rate between 50 and 100 percent, enough to both keep up with future growth and to add 66,000 homes to the housing stock that, had they been built over the last 20 years, would have prevented Oregon’s current shortage.

That will inevitably require figuring out how to bring homes to market at lower prices, and therefore how to develop market-rate homes with lower costs. Of those 66,000 missing homes, more than 50,000 would need to be at prices that only multifamily buildings, with their shared land, roofs, and utilities, can generally meet.

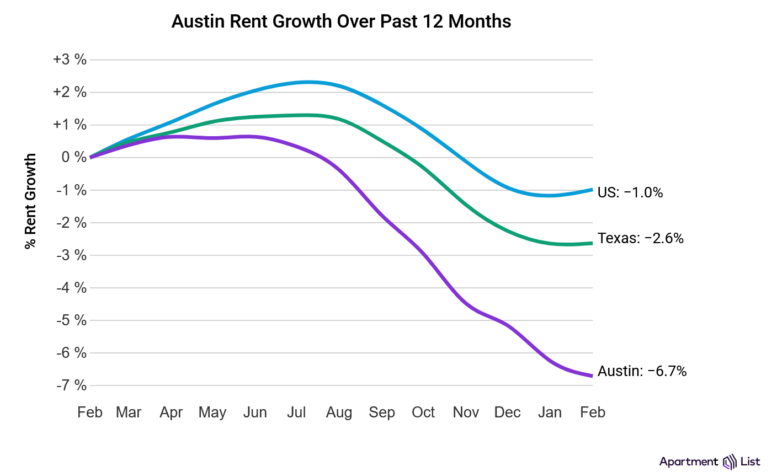

These are the low- to mid-price market-rate homes that the millions of Oregonians who live in market-rate housing rely on to keep housing market prices within reach. When more apartments get built, as they have been in almost unprecedented numbers in cities like Austin over the last few years, rents stabilize or fall.

But Oregon has seen no such boom in apartments. And unfortunately, despite various helpful and potentially helpful parts of the bill, SB 1537 would do very little to ignite one.

But Oregon has seen no such boom in apartments. And unfortunately, despite various helpful and potentially helpful parts of the bill, SB 1537 would do very little to ignite one.

Kotek’s 2023 bill would have loosened local rules against apartments

For supporters of infill housing, the heart of Gov. Kotek’s housing package when it was first introduced in 2023 was the part that essentially overruled local zoning rules.

Introduced as part of House Bill 3414, the concept was a Kotek original: sweeping, unprecedented, even wacky. It amounted to something like an abrupt upzone of the entire state.

How it worked: the exceptions to zoning that real estate developers regularly request, called “adjustments” or “variances,” would no longer be requests. If they applied to housing, the state would simply require local governments to approve those adjustments except in cases of health and safety. For example: most local zoning codes forbid buildings from being built directly against the edge of a property in most zones. The original version of Kotek’s 2023 bill would have automatically approved a request to build up to the edge of a lot.

Or, in the case of the Owens II project in Astoria: A project could be built without any on-site parking, despite the city code usually requiring 0.65 parking spaces per home. Building it with no on-site parking would resolve the stated concern of its opponents, Bob and Cindy Magie, who have said they object not to the building that would block their view (and the views of the Airbnb guests in the other building they own) but to the construction of an underground parking garage below it. They said they fear any excavation would endanger their property just uphill.

(This concern of the Magies about excavation is the remaining legal obstacle to construction of the Owens II, but it isn’t the only concern they’ve raised. According to a document summarizing Bob Magie’s testimony to Astoria’s Historic Landmarks Commission in late 2022: “The neighborhood has Victorian, Neoclassical, Mediterranean, and Craftsman construction. He felt this would not quite fit. The style does not fit the character of the neighborhood.” The Landmarks Commission, however, disagreed. After that decision was upheld by Astoria’s city council, the Magies turned their attention more fully to their concerns about excavation.)

Opposition from Oregon cities

Eugene Mayor Lucy Vinis testifies to the Oregon House of Representatives Rules Committee against the auto-adjustment section of HB 3414 in May 2023.

Kotek’s concept of automatically approving zoning adjustments was as sloppy as it was creative.

The bill had been inspired, in part, by a case in Troutdale. That Portland suburb had spent a year refusing to grant adjustments on parking and a handful of smaller design issues for a proposed apartment complex near its downtown, threatening to kill 94 below-market homes.

Some hated Kotek’s bill concept. Its leading opponent was the League of Oregon Cities, many of whose members—241 cities across the state—objected to the legislature taking an axe to their sometimes carefully crafted and painstakingly negotiated zoning codes.

“The proposal will render all but a narrow list of development criteria effectively irrelevant,” wrote Tom Ellis, mayor of the suburban City of Happy Valley.

Rep. Mark Gamba, a Milwaukie Democrat and former suburban mayor who generally votes as a pro-housing progressive, had a similar take. “All of those things that cities have put into place are at risk,” he said. “This definitely needs work.”

Ed Sullivan, a land use attorney who’s spent decades advocating for infill housing, teamed up with Carrie Richter, policy chair for the state historic preservation advocacy group, to be fiercer. “Better fit for the dustbin than the governor’s desk,” they wrote.

Others praised the automatic adjustment section as a match for the Kotek administration’s language about a housing emergency. The sloppiness and uncertainty, backers said, were the whole point.

“We must establish a regulatory environment that nurtures innovation,” said Rep. Maxine Dexter, a Portland Democrat who chairs the House housing committee and helped add to the bill an eight-year “sunset” date after which the auto-adjustment section would expire. “True innovation requires an environment that makes failing on a small scale acceptable. An ugly building that houses our neighbors now is better than a perfect building that takes years longer to be built.”

Kotek’s team scaled back the section further. But with various cities, historic preservationists, and some environmentalists still in opposition, the Democratic Kotek looked for votes across the partisan aisle instead. She made a deal with Republicans, adding to the bill a one-time expansion of urban growth boundaries that some cities favored. That move cost her many more Democratic votes without scoring quite enough Republicans. The bill passed the House but died in the Senate, a single vote short of passage, on the last day of Oregon’s 2023 legislative session.

The idea came back in 2024, but with an option for cities to mostly ignore it

After the 2023 session ended, Kotek stopped into a meeting of the “Housing Production Advisory Council” she’d convened, urging them to think big.

“This is a crisis,” she told the group. “We need more production. There’s no question about that. … If we just do the same thing we’ve been doing, we’re not going to produce enough housing.”

The advisory council responded by recommending, among many other things, that she come back in 2024 with a much bigger version of her auto-adjustment section. In addition to granting an additional story of potential height to most new buildings, their version of the bill would have also granted unlimited flexibility on the number of units in a building and the amount of floor space within the building envelope.

Meanwhile, in a separate series of video calls, Gov. Kotek’s negotiations with the League of Cities and its members were continuing. As they did, the auto-adjustment section got weaker instead of stronger. Drafts of the 2024 Kotek bill largely exempted any city that could show it had approved at least 90 percent of adjustments—a standard almost any city would likely meet, simply because developers rarely bother to formally request adjustments they don’t think they’ll get.

Then, just before the legislative session, a new concession: cities could also mostly ignore the auto-adjustments section as long as they could solicit “testimonials of housing developers” who’d recently received adjustments, saying that the city’s existing adjustment process was fair. (This passage is in Section 39(2)(c)(B) of the final bill.)

And what developer who hopes to do future business in a city, and had been granted the adjustment they requested, would turn down a request by that city to testify to the state that the city’s adjustment process had been fair?

“The exception completely guts the rule,” said Christe White, the attorney for the Astoria project.

An architect’s rendering of the proposed Owens II apartments, at left, in Astoria, Oregon. The owners of the property just up the hill have raised various challenges to the plan for 50 new below-market homes for seniors and people with disabilities. Rendering by Jones Architecture.

SB 1537 does other things for housing – just, not much for infill

Gov. Kotek’s bill does include a few other things that could help the Owens II and other infill apartment projects.

Sections 1 through 7 of the bill create a new “Housing Production and Accountability Office” at the state’s land use agency. This body would be empowered to both enforce state housing laws and provide jurisdictions with model codes, grants, and other potentially useful resources for accelerating homebuilding.

Sections 8 and 9 allow projects to opt into new zoning rules on the somewhat rare occasion when zoning becomes more flexible in the middle of a project.

Sections 10 and 11 might deter people from bringing tactical or frivolous legal challenges to housing projects. It orders Oregon’s Land Use Board of Appeals to require people who unsuccessfully challenge housing projects to cover any attorney fees paid to defend the project. That wouldn’t necessarily affect projects that don’t make it to the state land use board, but it would give appellants less leverage over projects they dislike.

Sections 24 through 35 create, and add seed funding to, a revolving loan fund to essentially put a cash bounty on projects that could deliver mid-price, market-rate homes. Though it’s a cleverly cost-effective way to subsidize mid-price homes, the legislature allocated just $75 million for the purpose—enough to unlock about 3,000 homes statewide in the first 10 years, and maybe twice that many over the life of that funding. It’d be about 0.8% of Kotek’s 10-year housing production target.

Sections 44 through 47 streamline a few discretionary decisions cities can take to allow replats, property line adjustments, and expansions of nonconforming uses within urbanized areas.

Sections 48 through 60 are the part of the bill that has drawn the most headlines: a limited, one-time urban growth boundary expansion insisted on by Republicans. That section, too, was scaled back since 2023 but remains controversial.

If local politics are a barrier to housing, optional state zoning laws will not change that

Then there’s the auto-adjustment section, now mostly optional due to Section 39.

One of its provisions would force some small changes. Cities that do not currently allow adjustments even to be requested—for example, to height limits in downtown Portland—would have to at least start letting housing developers request adjustments. But a city doesn’t have to grant those requests.

And after all, if a city wanted its zoning to be more flexible, it could just make its zoning more flexible. The whole point of state housing action is for state politics to do something that local politics can’t: get many cities to work together to end the housing shortage.

When a state gives cities an easy way to opt out of a housing law, this doesn’t work. Any local politics that have been blocking housing are likely to keep blocking it.

The Kotek administration has more chances to boost apartment construction

Announcing on Monday that her bill had passed the legislature, Kotek went out of her way to say that passage of SB 1537 was “not a finish line.”

Her housing production council wrapped up its business last month with lots of recommendations that haven’t yet been translated into bills. Kotek’s administration is also about to kick off months of work to implement three bills that passed in 2023.

HB 2001 and its companion HB 2889 set housing production targets for all larger cities and create an accountability system intended to motivate local housing reforms. Together, they might be a way to remove local zoning barriers that is firm, but less sloppy. And HB 3395 includes a provision that could boost construction of small multifamily buildings on small lots by introducing fire safety codes specifically for small-footprint buildings.

It’s not certain, however, that any of those bills will end up changing much of anything, either. That’ll depend almost entirely on the Kotek administration’s own choices. Which is why implementation of these bills will be the focus of future articles in this series.