There’s a lot of talk about the socio-economic privilege required to participate in alternative food movements. From Whole Foods’ nickname of “Whole Paycheck” to the lack of government subsidies going towards organic food, healthy eating is often considered an elitist luxury. So when efforts are made to cross the bridge between underprivileged communities and access to healthy food, it’s time to put down your locally-grown carrot for a minute and take note.

There’s a lot of talk about the socio-economic privilege required to participate in alternative food movements. From Whole Foods’ nickname of “Whole Paycheck” to the lack of government subsidies going towards organic food, healthy eating is often considered an elitist luxury. So when efforts are made to cross the bridge between underprivileged communities and access to healthy food, it’s time to put down your locally-grown carrot for a minute and take note.

In a new study, Real Food, Real Choice: Connecting SNAP Recipients with Farmers Markets, the Farmers Market Coalition and the Community Food Security Coalition show that Oregon has the highest percentage of farmers’ markets that cater to people participating in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), formerly known as food stamps. While California is ahead when it comes to the total number of SNAP-savvy farmers’ markets at 51, this accounts for a measly 10 percent of their total farmers’ markets in the state. Northwest states do better on market saturation. Coming in at 41 percent of the total farmers’ markets in the state, Oregon’s stats show a commitment to accessible produce (although Washington is standing at a not-too-shabby 32 percent!).

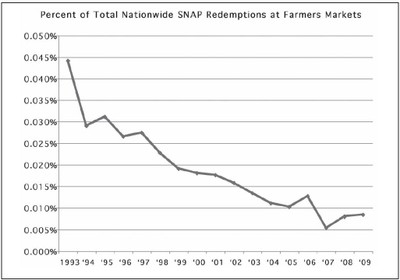

This is great news! But as the chart to the left shows, even the increasing number of farmers’ market SNAP redemptions is a minuscule part of the overall SNAP program. The steep decline seen in the graph is not completely explained in the report, due to a lack of research, but can be partially explained by the switch from paper coupons to Electronic Benefit Transfers (EBT) debit cards in 1996. While this switch achieved a less stigmatized shopping experience where debit card technology was already in use, it meant that markets had to contend with new technology and staffing that many could not handle. But awareness, training, and in some cases, state subsidized EBT machines are on the rise, and markets are embracing this path to social sustainability. If this is the case, why aren’t more people utilizing such a fresh, healthy source of food? The report offers some insight.

This is great news! But as the chart to the left shows, even the increasing number of farmers’ market SNAP redemptions is a minuscule part of the overall SNAP program. The steep decline seen in the graph is not completely explained in the report, due to a lack of research, but can be partially explained by the switch from paper coupons to Electronic Benefit Transfers (EBT) debit cards in 1996. While this switch achieved a less stigmatized shopping experience where debit card technology was already in use, it meant that markets had to contend with new technology and staffing that many could not handle. But awareness, training, and in some cases, state subsidized EBT machines are on the rise, and markets are embracing this path to social sustainability. If this is the case, why aren’t more people utilizing such a fresh, healthy source of food? The report offers some insight.

Price and Perception: OK, we get that organic food is usually more expensive than conventional. It’s not hard to imagine why most SNAP participants—heck, almost everybody—might perceive farmers’ markets to be more expensive than other food sources. And while there isn’t a whole lot of research comparing actual prices, there’s some evidence that the price of market products often decreases when there’s a direct farmer-to-consumer connection. Without the middleman to split costs with, market prices can be lower and more consistent than grocery store items.

Access, Hours, and Convenience: Inconvenient hours and location can be big deterrents to shopping at a farmers’ market, especially if you are working multiple jobs or juggling work and child care. Markets also do not cater to people who need one-stop shopping; there aren’t usually stands selling household staples like paper towels and laundry detergent, for example. One way to reduce this inconvenience is to increase the number of farmers’ markets in an area. The Seattle Farmers Market Alliance boasts seven markets, some of which are open on weekends while others take place on weekday afternoons. It’s not a complete answer, but it gives shoppers some extra flexibility.

Cultural Barriers: Perceptions play a big role in shopping routines, and if immigrants or people from minority ethnic groups feel that they won’t be able to communicate, they may favor the relative anonymity of grocery stores. There is also the issue of culturally appropriate foods being offered; some minority groups might favor stores that import products from other countries.

Although the report dishes up a hefty 77 pages of data, I was left with some questions. Just who are the SNAP participants shopping at farmers’ markets and what demographics do they represent? While the report summarizes the demographics of SNAP participants in general, it seems to treat farmers’ market-frequenting EBT users as one giant, homogenous group. How many of them have children? How many are recent immigrants? How many come from historically marginalized communities vs. the recently unemployed middle class? Distinctions are key to understanding how markets can create a more inclusive space for EBT users.

At the end of the day, shopping at a farmers’ market it still a political act. Market shoppers are supporting local food systems, small farmers, organic production, and seasonal eating, and the growing number of shoppers gives markets the flexibility to explore programs like SNAP. So when you feel good about getting your apples directly from the source, remember that you are also supporting this service for a SNAP participant in your neighborhood.

News update: The Senate and House recently passed two pieces of legislation that will allocate $26 billion for Medicaid and educational funding, and President Obama signed it on August 10th. To pay for this all? Cutting almost $12 billion from the SNAP program. Some say this is warranted because of last year’s stimulus boost to the program, but many are outraged at this attempt to take from the poor to give to the, well, poor.

Token image courtesy of Flickr user cafemama under a Creative Commons license.

Chart from the Real Food, Real Choice report, used with permission.

Briggs, Suzanne, Andy Fisher, Megan Lott, and Nell Tessman. Real Food, Real Choice: Connecting SNAP Recipients with Farmers Markets. Community Food Security Coalition and the Farmers Market Coalition, June 2010.

Scott Davis

What an enlightening piece! I am amazed by your ability to dissect the details of the SNAP program, and to appreciate the nuances of obtaining groceries as a public and personal experience. For example, the switch from food “stamps” to food “debit cards” seems like a quite reasonable explanation for the falling % of SNAP funds used at farmers markets.To comment on the cultural barriers you bring up, I believe that in the long run farmers markets actually have a stronger potential than grocery stores to facilitate cross-cultural understanding and food production. The faces behind farmers markets can learn about what foods new neighbors grew in their native lands, learn what languages exist in their communities, or even better, learn some things they have in common instead of just what their differences are.I self-checkout register will never ask a customer if they found all they foods they were looking for.It seems to me that cost, accessibility, and general skepticism will be the greatest challenges for farmers markets to overcome before they are something that the broad public engages in, irregardless of wealth. I am so glad that Washington and Oregon are on their way there.Thanks for the knowledge

Tony Dondero

Interesting piece. It’s noble to expand access to Farmer’s Markets but it’s still a small niche and probably always will be. Farmer’s markets are fun, a great place to hang out and shopping at them may be a “political act,” to some. I worked at an organic flower farm in Oregon near where I grew up, for a summer as well as another six-month stint during a break from college, and saw the problems and successes of such an operation. I concluded that that so called alternative lifestyle wasn’t really so alternative once you broke it all down. (The husband of the husband-wife team who ran the place made his money in the energy business,–she was an accountant—and incidentally the pay was low and of course there was no health insurance, fine for me at the time but the only adults who would honestly commit to that job for more than a couple months of time were a small core group of Mexican immigrants and temp Mexican immigrants when the flowers popped; the Dutch immigrant and his American wife who worked there complained a lot and eventually quit. If I wasn’t living at my parent’s house, I would have certainly qualified for food stamps). Farmers markets are fine but grocery stores are still the main source for most of the food, including organic that we will eat. In terms of saving fuel, a large, full semi trucking produce from California to grocery stores and restaurant suppliers is likely more efficient than 25 or so small trucks from around the Puget Sound burning fuel to get to a farmer’s market. Some consolidation is possilbe but not always. Also, I can walk to two grocery stores (Central Market and Safeway) and a Walgreen’s that sells milk near where I live (or drive two minutes to them or five minutes to a Albertson’s) versus driving across town on a Saturday five or six months out of the year to go to the Farmer’s Market. It’s nice to have something new and choice (probably the top benefit of capitalism) at a Farmer’s market, but I think placing requests for fresher, healthier stuff we want at the grocery store down the street and influencing how things are done through consumer demand might be wiser, cheaper and quite possibly better for the environment. If there’s demand for a product, grocery stores will stock it, but there has to be a willingness to pay. Instead of creating more Farmer’s Markets, I think it’s better to get organic growers to sell more goods to grocery stores. Of course the ideal might be co-ops like the ones in Mount Vernon and Capitol Hill. My hometown had one when I was young but sadly it did not last.

Eric Hess

From personal experience, I think it can often be cheaper to buy seasonal produce at Farmers Markets or local grocery stores. Mega-chains like Safeway tend to price a lot of produce without much relationship to seasonality, while local outlets move more with the seasons.