More low-intensity fires could have prevented the megafires that turned 700,000 acres of forest into a “moonscape” and incinerated more than one billion board feet of timber. That is what the Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation claim in their lawsuit against the US government. There is good evidence backing them up.

Even with more flexible policy and some redistribution in funding, federal and state wildfire response still does not follow science-based recommendations to allow wildfires to burn when conditions are low-risk and to use intentional controlled fires to restore forest health and climate resiliency.

Of course, there is no one-size-fits-all solution to our wildfire problem. As William Bagley, a seasoned fire professional and emergency manager for the Klamath Tribes, told me, “Fire’s not rocket science. It’s a lot more complex.” Still, it’s clear—especially in seasonally dry inland ecosystems—that forests need more fire, not less.

Cascadia is stuck on a wildfire treadmill

Cascadia, along with the rest of the West, is caught in a vicious circle: the more we suppress fires, the worse they get; and the worse fires get, the more we suppress them. It’s such a ubiquitous pattern, and such an entrenched and difficult problem, that it deserves naming. Let’s call it the wildfire treadmill.1 (Sightline has illustrated the concept above. A higher-resolution version is available for download and use here.)

Wildfires have become larger and more ferocious than previously imaginable, and we are seeing more of the megafires that destroy communities and that no amount of firefighting can contain. As the planet warms, most areas in western North America will experience a doubling or more of their fire risk.

The three culprits that put us on the wildfire treadmill are:

- Climate change and the accompanying increase in those hot and dry days with strong winds that spread fire rapidly and make extinguishing fires very difficult, called “fire weather”;

- The buildup of “fuels” in the forest: small trees, shrubs, debris, and dead wood; and

- The expansion of the wildland–urban interface (WUI), where houses meet or intermingle with undeveloped wildland vegetation.

Smokey the Bear statue warning passersby of “Very High” fire danger (source: Oregon Department of Forestry).

Ironically, the accumulation of forest fuels is a direct consequence of state and federal policies that since the 1600s in one Canadian province and the early 1900s nationwide in the United States have mandated the immediate suppression of all wildland ignitions. For decades, indigenous Americans caught using cultural fire were often jailed or worse.

Now we face a daunting predicament: having snuffed out nearly every ignition for over a century, we’ve suppressed ourselves into a corner where even a small and innocuous flame can explode into an uncontrollable megafire. So, we continue to fight nearly every fire.

A fire in time saves nine

Small, low-intensity fires now, while unpleasant and dangerous, mean fewer large, high-intensity fires later. It’s when a fire is hot enough to burn the entirety of mature trees, called crowning or torching, that higher-intensity fire can take off. At this point, the fire can spread embers across long distances and can become a “crown fire” that spreads from treetop to treetop.

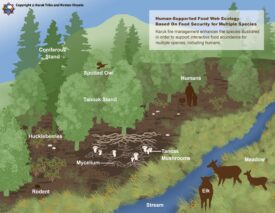

Historically, smaller and patchier fires frequently swept through Cascadia’s seasonally dry forests, clearing out forest fuels. Indeed, throughout the bioregion, much of this fire was intentionally started by indigenous people who used it to prevent more dangerous fires, stimulate seed germination, recycle nutrients, and create open habitats for the plants and animals they relied on for food and fiber.

These lower-intensity fires travel along the ground, fueled by grasses, fine fuels, and small trees. Fire-adapted species, such as the ponderosa pine, with its thick fire-resistant bark, can survive low- and mixed-intensity fires. And these fires, every 15 to 20 years, make it unlikely for any one ignition to grow into a high-intensity fire. The footprint of a past fire also can act as a natural fuel break and can provide access for firefighters.

Ecosystem restoration burn in South Okanagan, BC (source: Province of British Columbia; cropped from original).

Now, farsighted leaders in the West, from Indigenous groups to the US Forest Service, are trying to step off the wildfire treadmill by carefully using wildland fire to clear out accumulated fuels. During safe weather conditions, fire professionals carefully reintroduce fire using prescribed burns and “managed wildfire for resource benefit,” the clunky term of art for attentively monitoring a wildfire instead of immediately suppressing it. Mechanical treatments, including thinning out small trees and debris ahead of time, can both reduce fuels and make it easier for crews to move around as they manage these active fires. However, when not followed soon by fire, these treatments may actually make fires worse.

It’s important to note that forests of different vegetation types, elevations, and moisture conditions respond differently to fire and fire management. For example, fuels reduction does not seem to mitigate fire severity in the cooler and wetter forests west of the Cascades.

Authorities monitored this wildfire as it burned along the forest floor without torching the treetops (source: US Forest Service).

The good work of healthy forest fire

Increased community safety

Protecting lives, homes, schools, and infrastructure from devastating conflagrations such as the Paradise and Lytton fires is the driving concern behind public efforts to return “good fire” to the land in seasonally dry forests. Regional strategies focus on reducing hazardous fuels in those firesheds where communities are most at risk.

Less smoke for better air quality

Low-intensity prescribed underburn in the wildland urban interface, western OR (source: US Bureau of Land Management; cropped from original).

Planned fires can also improve Cascadia’s growing air quality problem. Most obviously, more frequent but lower-intensity fires can spread out particulate pollution, making it less intrusive and dangerous.

Additionally, in theory, fire professionals can plan prescribed burns for times when forest fuels are dry: just like chopped firewood, wetter fuels create more smoke. As Mike Petersen, vice-president of the Northeast Washington Forest Coalition, describes, “With a prescribed fire, you can kind of hone in on what kind of moisture level you want, and you plan it for a week or so before a big rainstorm so you can put the thing out.” Managers can also plan burns for times when the wind will blow the smoke away from communities and avoid thermal inversions that trap smoky air close to the Earth’s surface.

Greater carbon storage potential

Paradoxically, more fire also can dampen emissions of carbon from forests. Many people, including many media outlets, assume that all wildfires send sequestration gains up in smoke, that “when a tree burns, … that carbon is released back into the atmosphere.” The specifics are complex, but a few general ideas can help explain why that’s not necessarily true.

Fires that clear out forest fuels can create more carbon-dense and carbon-stable forests. Most forest carbon is stored in the trunks of trees. By thinning an over-dense understory, low- and moderate-severity fires free up resources to help larger trees mature into bigger carbon warehouses. Bigger trees also tend to be more drought- and fire-tolerant, a vital feature in a warming climate. These lower-severity fires also help prevent severe fires that can permanently convert forest into carbon-poor shrublands and grasslands. Finally, even when mature trees are killed in fires, most of their carbon remains in the dead trunks, releasing gradually as new growth sequesters carbon.

Improved forest health

This serotinous cone from the fire-adapted lodgepole pine was opened by fire, allowing it to release its seeds (source: US National Park Service).

Beyond smoke and carbon, there is wide agreement among ecologists that fire is one of the most essential influences on western forests and that more fire is needed on most landscapes. Dense forests crowd out the flight corridors that birds of prey need for hunting and the sunny clearings that bears need to forage for berries. By keeping forests open, wildfire creates key habitats.

Wildfires also contribute to species diversity by opening gaps between clusters of trees, leaving some old stands and creating some young stands, thus allowing for a range of different light and moisture conditions that suit a variety of tree and shrub species. Some species, such as the lodgepole pine, need fire to release their seeds from “serotinous” cones. Diverse and healthy forests are more resistant to the spread of insects and disease.

How do we say yes to fire?

It seems the wildfire crisis has pushed the US government past a first tipping point. Policy is finally responding to scientists’ call for more fire. The US Forest Service’s ten-year plan calls for more prescribed burn, and the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act of 2021 added $1.7 billion for forest restoration and wildfire risk reduction.

But will it be enough? Policy has been changing since the 1970s, but on the ground, forest managers still face a system of incentives and liabilities that pushes toward suppression and away from managed wildfire and prescribed burn. Each year, despite intentions, new wildfire emergencies cancel plans to get more fire on the land. Authorities kick the can down the road, relieving short-term fears at the expense of a long-term solution.

In 2021, the Forest Service prohibited managing fire for resource benefit and limited most prescribed burning. In 2022, it directed a full moratorium on all prescribed fire. In both years, while some regions burned, others had exceptionally cool, wet, and safe conditions. Adam Gebauer, Public Lands Program Director at the Lands Council, explained the rare missed opportunity. “Given the limited amount of burn windows that we have here in eastern Washington, this would have been one of the better years to get a lot of prescribed fire on the ground.”

We have the technical know-how, but as a society, we’re only at the beginning of learning to live with fire.

Max Moritz, professor of wildfire dynamics at the University of California, Santa Barbara, told me, “We struggle to use fire as a tool because we’ve sprinkled homes and communities across many of these landscapes. If we could roll back time and unsprinkle all those homes, or if we fire-hardened those communities, we could probably use fire in a lot of different ways that we’re not comfortable with now.”

The first step to getting off the wildfire treadmill is, in the words of Kara Karboski, who coordinates prescribed burns in Washington, “seeing the landscape and the trees as something that needs fire. When we do have smoke in the air from burning, we need people to understand and be supportive of the work that’s happening. If we have this cultural shift, maybe we can pass better laws and building codes.”