As more cities and states lift costly parking mandates, what will happen next? Chris Hawley has seen the future.

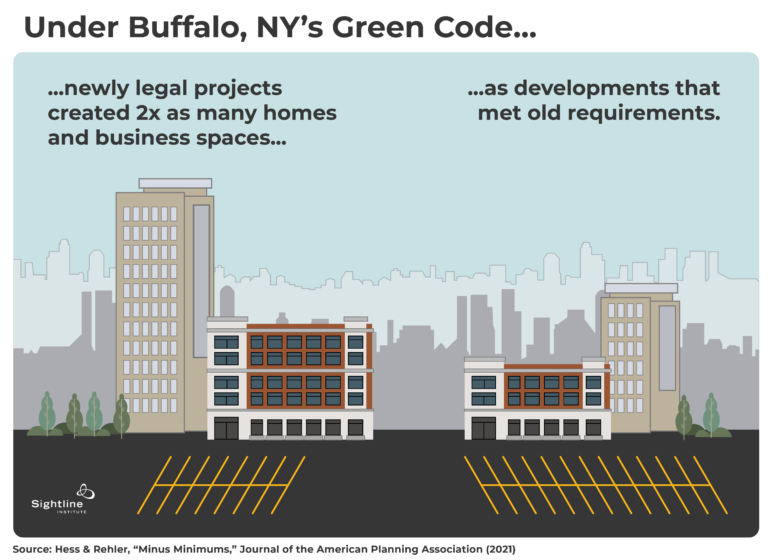

Hawley, first as an activist, then as a city planner in Buffalo, New York, worked to remove minimum parking requirements citywide in 2017 under the city’s new form-based “Green Code.” (“Form-based” focuses on building form, including its physical appearance and relation to the street, rather than regulating uses, like commercial or residential.) Now five years later, Buffalo’s population is experiencing significant growth for the first time since the 1920s, and new homes and businesses are popping up left and right. Hawley shares the story behind the numbers.

Chris Hawley. Photo by Buffalo Obscura, used with permission.

Can you start by introducing yourself?

First, I was an activist advocating for a new zoning rewrite, along with friends of mine. We felt that the zoning code was the core problem behind a lot of our development controversies and was a stumbling block to get the walkable, mixed-use development that was consistent with our historic character. The 1953 zoning code—adopted the same year that Elvis Presley recorded his first song in Memphis—was ancient. It had been overlaid hundreds of times and grown to an unsustainable 1,804 pages of regulations.

We were in a good position with our new mayor Byron Brown to throw everything in the garbage and start from scratch. He remained committed through politically difficult conversations, which included 242 public meetings over a seven-year period.

Sounds grueling and expensive.

Writing a zoning code doesn’t involve many ribbon cuttings. But I think that Mayor Byron Brown understood that once the new zoning code is adopted, every ribbon cutting is a victory for the Green Code, which is what we ended up calling it.

The new development code is 338 pages long, a fifth of the size of the previous code.

A lot of planners advocate for a much more incremental step-by-step approach to adopting form-based codes. That is expensive and doesn’t provide a lot of returns for a municipality, if you are applying it only in very small areas.

There is an advantage to a complete rewrite of your land use and zoning regulations, which South Bend [Indiana] and Hartford [Connecticut] have also learned. When we tackle individual topics, particularly controversial ones, on a bite-sized basis it’s easy to get stuck politically—the common council spent eight months on a chicken coop ordinance. But when it’s one giant package, that can mute controversies about particular elements, whether it’s height or density or certainly whether to have minimum parking requirements.

What kinds of changes have you seen in Buffalo since getting rid of parking requirements?

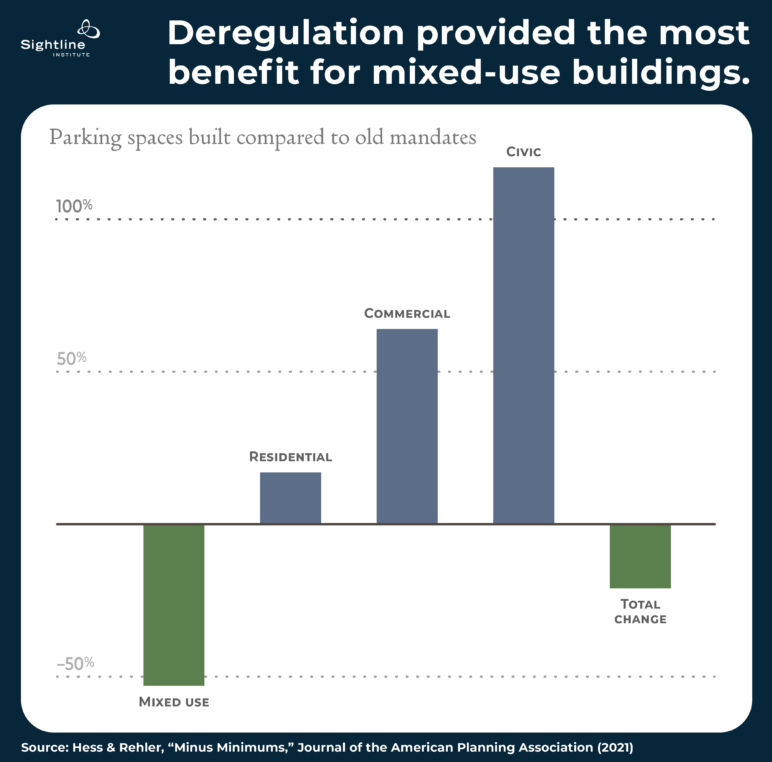

Daniel Hess, a professor at the University of Buffalo, looked at the first two years of development activity that went through major site review. He found that developments were providing less parking than was required under the old code. In particular, mixed-use projects often provided substantially less.

We have a few cases of new construction where zero parking was provided. 15 Allen Street was our first zero-parking construction project. It was one block from a metro rail station and had 12 units of housing and two shopfronts. Another one was for 201 dwelling units downtown close to a public library and adjacent to a new grocery store.

We have a few cases of new construction where zero parking was provided. 15 Allen Street was our first zero-parking construction project. It was one block from a metro rail station and had 12 units of housing and two shopfronts. Another one was for 201 dwelling units downtown close to a public library and adjacent to a new grocery store.

I really wish that study had looked at staff-level reviews for smaller-scale projects. I think if that had been undertaken, their findings would have been even more pleasantly surprising. Smaller projects in particular benefited the most from the elimination of minimum parking requirements. Big developers with big projects have a lot more capacity financially to provide parking if they want to. Under the old code they could always get variances: they have expensive attorneys and relationships in City Hall. Smaller-scale projects don’t have those kinds of resources, or they’re constrained by the size of the site.

Mixed-use is a lot easier now. We relaxed density restrictions in residential zones and eliminated them entirely in mixed-use and downtown zones. We even legalized some degree of mixed-use within most residential zones. We have a tradition in Buffalo of corner shops and taverns that are kind of mixed in with our neighborhoods, sometimes mid-block too.

One of my proudest achievements in the code allows commercial buildings built before 1953 to be reused for a wide range of commercial uses regardless of what zone it’s located in. That has led to a flourishing of new immigrant enterprises in our working-class neighborhoods, where we’re seeing the largest increases in population.

I bought a corner tavern, which had long been shuttered. It could not reopen without a use variance under the old code. There was no off-street parking. As a result of the new code, I was able to reopen the tavern as a nonprofit social hall. Dozens of entrepreneurs have been able to undertake similar projects across the city without any real regulatory hurdles.

A 1914 pre-prohibition bar reopened for the first time since 1991, after being purchased by Chris Hawley in 2020. Photo by Eugene V. Debs Hall.

Has overall development activity increased?

Absolutely. They don’t make the news as often as they used to because we increased the threshold for projects that require a public hearing, which is a significant change.

Under the old code, we basically adopted mandatory site plan review for virtually any project over $50,000 in value regardless of its character or routine nature. Now on average, if it’s a smaller-scale project that meets the letter of the code, they’re guaranteed to get their building permit within 30 days.

I can say with confidence that the increased level of development that we’re seeing is much higher-quality. Before, conventional suburban development was the norm, and now walkable mixed-use development is the norm. Developers generally favored the code change because of the easier process. They told us consistently that the best thing for investment is predictability.

What are the politics around parking in Buffalo?

What are the politics around parking in Buffalo?

We are a Rust Belt city, and we’ve lost about 55 percent of our population [since the 1950s], so we don’t have the congestion concerns you might see in other cities like Seattle or Boston, where on-street parking constraints are a major political football. There was only one neighborhood where parking was a significant concern. Most people were surprised we even had minimum parking requirements.

Our experience since 2017, when the code went into effect, has been very, very good. We’re no longer requiring variances if you want to provide less parking or no parking, so it doesn’t come up as often. Before the new code was adopted, when residents got a notice in the mail saying that a developer or business owner wanted to move forward on a project and provide less parking than the minimum, that created controversy and conflict. In meetings we have about development now, parking just doesn’t come up as often. That’s one of the most unexpected and pleasant surprises that have come out of these five years we’ve had the code in place.

A question that regularly comes up for me is, if you get repeal parking minimums, do you need a holistic parking management plan to go with it?

To make the abolition of minimum parking requirements palatable, we adopted a required [transportation demand management] TDM plan for projects of a certain size, which requires a developer to explain what the anticipated travel demand is, and then how that travel demand will be accommodated. It doesn’t require you to provide parking but does require you to push for transportation alternatives like biking and walking.

I wouldn’t say we have been tremendously successful with TDM—we’re still trying to figure out that route. My only note of caution for other municipalities without large planning staffs is that managing a TDM plan requirement or other parking management strategies can be very time-consuming and burdensome on regulatory staff.

Are there noticeable places where on-street parking has gotten busier? That is always at the top of the list of concerns.

As neighborhoods become more popular, certainly parking supply becomes more constrained. We’re doing more to track this downtown than anywhere else, but the anecdotal experience is there is still available parking for folks. We’re using market-based pricing to manage demand on our public parking supply. We’re still, of course, emerging from the pandemic. There simply just isn’t the kind of demand that existed before.

What parking management tools do you deploy?

Downtown, we have variable parking rates so parking can be anywhere from free to relatively expensive. That’s a system of tools that we were putting into place before the pandemic started. The whole notion is that at any given time, at least 10 percent of the parking spaces will be open, so that people don’t perceive that there is a parking constraint.

We have only one residential permit program in a neighborhood called the Fruit Belt. We have a growing medical campus on the edge of downtown with 17,000 employees, and some of those employees decided to park in the adjacent neighborhood rather than the paid ramps. The common council rushed to create this pilot residential permit program.

It’s important to consider that about 30 percent of households in Buffalo do not have a car at all, largely due to poverty rather than by choice. All neighborhoods are still served by public transit, and we have a really strong bike culture in Buffalo. Relative to other American cities, we started off with a really good base. What we’re trying to do is build a city where you can thrive without a car, rather than simply survive without a car.

This transcript was edited for brevity and clarity.

Mira Kamada

I think it’s still short-sighted to not provide parking to residents and guests. You said it yourself, most people in the area don’t have cars because they can’t afford one, not because they don’t want one. This model discourages people who can afford and want a car from living in a more sustainable environment. The best place I lived was in an urban high rise with a parking garage underground. Most services were within walking distance. We rarely drove, but the car was available when needed. Unfortunately that is not life in America. I would appreciate a more nuanced and realistic approach to Sightline’s push to eliminate parking.

Julian Zavaglia

This is incredible, I’m honestly in utter shock that such rational and sustainable pro-human development is being done in Buffalo. Cars are a blight on our society, any city that moves fervently in the direction of making car-less cities is a city that will thrive. The idea that they give us freedom is a sick joke, they cost us dearly and make it so difficult to really enjoy even cities built around cars. They just are a bad way to do transportation in urban environment. Buffalo has rail, trolleys, buses, from what I understand it could be better, hopefully these code changes will foment development in those areas as well. Buffalo just entered the small list of cities I’d want to live in.

Andy

“This model discourages people who can afford and want a car from living in a more sustainable environment.”

You act like there’s no such thing as street parking. Lots of cities like NYC or Boston have neighborhoods where it’s street parking only and people with cars manage quite well. If a person absolutely needs a dedicated parking spot, then maybe they should stick to the suburbs as they clearly don’t want to adapt to a more sustainable environment. They want the environment to adapt to their needs.