For years, the City of Troutdale, Oregon, has pushed other government agencies to force the people living in tents along nearby riverbanks to move somewhere else.

Situated on the Columbia and Sandy rivers five miles east of Portland, the city of 16,400 that bills itself as the “gateway” to the spectacular Columbia Gorge has far more low-income residents than low-priced homes, according to a city-commissioned analysis. Zillow estimates that average monthly rents in Troutdale recently exceeded $2,000, a 29 percent jump in 18 months.

Last year, a Troutdale city councilor personally led what the mayor of a neighboring city called a “group of vigilantes” to illegally tear down riverside campsites using “a Bobcat and other tools.” They had organized on Facebook and were under the impression that the sites were unoccupied at the time and the objects they threw away were unused garbage.

The tensions haven’t stopped there.

This fall, as other government agencies have worked to fund and design a local project with 94 homes at a range of below-market rents, Troutdale has been saying: no, no, no.

Base monthly rents in the proposed cluster of three-story buildings would range from $559 for some studios to $1,438 for some two-bedrooms. They’d be two blocks from the city’s historic downtown core and two TriMet bus lines.

Troutdale officials insist that an affordable housing project proposed for their city include 26% fewer homes so it can make room for a bigger parking lot.

The city’s complaint: city officials say that 94 apartments is too many for 130 parking spaces. Troutdale is insisting that the project instead eliminate one of its three buildings to make room for a bigger parking lot.

The 94-home proposal from Home Forward, the county’s federally affiliated affordable housing provider, is exactly the sort of project Oregon’s state land use commission had in mind in July, when it unanimously voted to roll back parking mandates in most urban and suburban areas, especially for homes that meet affordability standards. If that rule takes effect on January 1, 2023, as scheduled, the Home Forward project would be able to move ahead with 130 spaces for 94 homes.

But if the City of Troutdale has its way, the new “Climate-Friendly and Equitable Communities” rules won’t take effect on January 1. Troutdale is one of nine cities around the state that have agreed to sue to block them.

Similar projects nearby have much more parking than they need, developer says

Troutdale officials say they’re bringing the lawsuit as a matter of principle, not because it would give them more leverage in this high-profile negotiation with what’s effectively a different branch of government.

Home Forward, meanwhile, says it’s trying to keep a commitment to taxpayers. Sixty percent of metro-area voters agreed in 2018 to fund at least 111 new affordable homes in east Multnomah County alongside thousands of others around the region.

Based on its review of the number of cars parked overnight at similar affordable housing projects in Troutdale and nearby Fairview, Home Forward estimates that the future residents of the 94-unit building it aims to construct would probably need space for about 103 cars.

Image from Home Forward’s presentation to the Troutdale planning commission.

But Troutdale requires parking lots in new residential buildings to have no less than two parking spaces for every home, even a studio apartment. Over the summer, Home Forward approached the city with a proposal: it would eliminate one of the two garbage and recycling areas originally planned for the site. This would bring the parking count to 130, 27 more parking spaces than it estimates its future residents will use. But it wouldn’t require eliminating any homes.

That was still 31 percent less parking than the city generally requires. On September 14, Troutdale’s planning commission rejected that compromise after hearing a series of local residents criticize the project. The concerns raised ranged from curbside parking shortages in front of nearby businesses to a worry that children living in the two-bedroom homes might, in the absence of additional playground equipment, turn to crime.

The planning commission agreed not to make any exceptions for the affordable housing proposal. They also overruled city staff by rejecting various other negotiated compromises, including allowing an unused city cul-de-sac to become part of the property in order to fit more parking spaces on site.

Home Forward subsequently asked its architecture firm to figure out how many homes would need to be cut to follow Troutdale’s parking mandates. The answer: 24 homes, more than a quarter of the project.

Excessive parking mandates frequently block low-cost homes

As Sightline wrote in July, project after project in Oregon has hit the same barrier over the years: city codes that forbid the construction of homes without also constructing more parking spaces than the residents are likely to actually use.

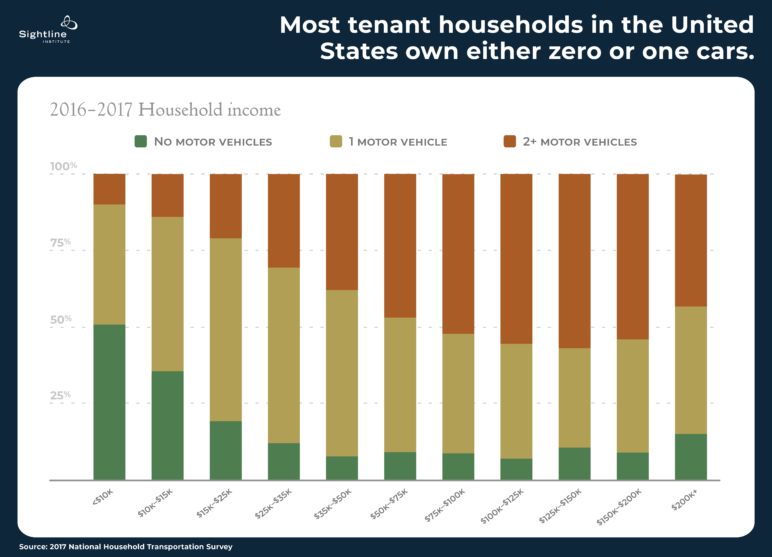

These bans on low-parking homes were typically written years before and applied citywide regardless of local circumstances. In most cases, they apply even to homes specifically targeted at low-income Oregonians, who—beyond being in deeper need of affordable housing—are statistically less likely to own as many cars.

Data: 2017 National Household Transportation Survey.

Last summer, 41 housing, business, transportation, and environmental groups from around the state expressed support of Oregon’s parking reforms. Home Forward was one of 12 affordable housing providers to join.

Anyeley Hallova, then the vice chair of the state’s land use and development commission and a developer of affordable housing projects herself, said in May that by removing parking mandates, the rules would remove barriers to fitting more affordable homes in more walkable areas.

“In the past, a lot of our more affordable housing has been concentrated in certain areas of cities, or in certain cities and not in other cities,” she said.

Opposing the rules were a variety of local governments. Some, though not all, cited the parking reforms.

“Since I’ve been on council for 10 years now, I can sum up in three words some of the most important issues: parking, parking, parking,” Eugene Councilor Claire Syrett told the commission in May. “It is a huge topic that you don’t expect when you join city council.”

Voters in Syrett’s district removed her from office last month in a low-turnout recall election motivated, in part, by a group of Eugene homeowners who support banning the construction of new homes without off-street parking.

Since the state rules’ passage on July 21, at least nine cities have voted to join a lawsuit to block them. The cities are expected to claim that the state land use commission exceeded its legislative authority.

State law orders the commission to set rules that will, among other things, “avoid principal reliance upon any one mode of transportation” and “minimize adverse social, economic and environmental impacts and costs.”

Lawsuit is about ‘Extreme timelines,’ city official says, not blocking housing

A parade through downtown Troutdale, a few blocks from the proposed project, in 2015. Photo by Jeff Muceus (Creative Commons).

Troutdale’s mayor and city manager referred requests for comment to David Berniker, the community development director. Berniker, who has been on the job for three weeks, said in an interview Friday that he believes Troutdale would be suing to block the state rules regardless of its simultaneous dispute over the Home Forward project. “I think the folks that are responding to CFEC are responding to policies and extreme timelines that are coming down from the state,” Berniker said.

He said that though it’s not technically complicated remove parking mandates from city code, the city wouldn’t want to make that change without months of expensive outreach to Troutdale residents.

Berniker, who has a background in architecture and planning, added that though it would be technically possible to fit 94 homes on the site, he couldn’t say whether the city might eventually agree to a deal that allows that many to exist.

“Personally, my hope is that we’ll reach a middle ground on the parking and on design elements,” Berniker said. “I think there’s support for the project. It’s not universal, but there is definitely support for this project in terms of completing a complete, connected, cohesive community.”

Another interested party is Multnomah County Commissioner Lori Stegmann, who represents the Troutdale area and signed off on the deal for the county to donate 3.5 acres of land, worth more than $1 million, to the Metro-funded project.

“Commissioner Stegmann was extremely disappointed to hear about the position of the planning commission,” her chief of staff, Rebecca Stavenjord, said in an interview. “Providing additional affordable housing options in Multnomah County, especially east Multnomah County, is an incredibly high priority for the commissioner.”

Sightline researcher Catie Gould contributed to this report.

Correction 11:41 a.m.: A previous version of this article gave an incorrect deadline for cities to appeal the state parking rules. Oregon sets no deadline for a substantive appeal.

Bryan Jacobson

Exactly what “similar developments nearby were built with more parking than residents will need”?? Every apartment complex I see has every spot filled plus most or all nearby street parking full. I call BS on the whole premise of this article. Show me empty apartment parking spots at 8pm.

Michael Andersen

Home Forward sent someone to five nearby sites to count cars in the 11pm-midnight hour and again in the midnight-1am hour. The sites: Troutdale Terrace, Cherry Ridge, Fairview Arms, Fairview Oaks and Woods, Kings Garden.

Every lot had more than 20 empty parking spaces; one had 116 empty spaces. The highest occupancy per unit was Troutdale Terrace, with 1.5 (so, even they use 25 percent less parking than the city generally requires).

Where do you live? Maybe it’s in a city with less onerous parking mandates than Troutdale.

Adrian Koester

As someone who sat though all of the presentations and testimony in front of the Planning Commission, and as someone who read through the material submission (original and revised) in great detail, I say that this article does not come close to fully characterizing all of the concerns that were raised regarding this project.

The headline issue was indeed parking, but that is only because that was the largest variance that was being deliberated. There are far more concerns raised related to the scale proposed, the design, and the specific site in which it was proposed.

I have no issue with low income housing in general or in this specific location. I also do not necessarily believe that a project in this location would need to hold to the parking code to the letter. The scale of the project simply does not make sense relative to the community that Home Forward purports to attract. There is simply not enough access to basic necessities (food, transportation, medical, etc.) for the population of fixed income residents that this is being designed around. Those residents that have the ability to travel for work and daily necessities will need parking.

If we are going to provide low income housing, it needs to be designed and placed in such a way that it will actually provide a high quality of life to the residents it is intended to attract, as well as be able to seamlessly work with the surrounding community. Everything that I saw in the submission from Home Forward did neither.

Michael Andersen

Thanks, Adrian. This piece focused mostly on the parking issue because it’s relevant to the broader statewide reform and because, as I understand it, parking is the main leverage point the city has over this project. The city doesn’t have much power to micromanage the scale, design and other issues, any more than it does for any other home being newly built in Troutdale.

Do you live in Troutdale? Do you feel it offers you a generally high quality of life, despite what I’m sure are some downsides?

Adrian Koester

I do live in Troutdale, and the proposed project is visible right out my front door. I do feel that Troutdale offers a good quality of life IF you have reliable transportation. I do feel access to public transit is woefully insufficient, something that would need to improve greatly if you were to put housing designed for people with no car in the middle of what amounts to a food desert.

As for the ability of the city to affect the design, there was a list of code variances that were denied by the city, not just parking. That was just the headline item.

Stephen Slattery

Government(tax payer) funded low income housing. Some of us remember the late 1950s 1960s debacles, ie Pruitt Igoe( infamous disaster in my home town of St. Louis, Missouri) What possibly could go wrong???

Joseph Eisenberg

You don’t need to imagine. Home Forward already operates dozens of apartment buildings throught Multnomah County, including just next door in Fairview and Gresham: https://homeforward.org/apartment-communities/ – for example Fairview Oaks at 22701 NE Halsey “Fairview Oaks consists of 328 one, two, three and four-bedroom flats and townhome-style homes. The community includes 40 project based subsidized apartments.” You can go buy and check it out. It’s your usual suburban apartment complex, but happens to have subsidized units. It’s not much like the 11 storey concrete buildings with 2800 units in St Louis that you mentioned.

Joseph Eisenberg

The project isn’t expecting people to have no car, it’s providing more than one parking space per unit. It is likely that most households will have 1 car. But some will take the bus and walk, if they can’t afford car payments and insurance. This location (1 block south of the corner of Halsey and 257th) is really central, it’s across the street from food carts, a 3 block walk from the heart of historic Troutdale including the police station, city hall and shops, and, 2 blocks from the Columbia Gorge outlet mall.

It’s also block or two from 30 bus stops: the 77 bus on Halsey to Portland, which will be upgraded to frequent service, the 81 bus and the 80 bus to Gresham (and the MAX station).

It’s just about the best location in all of Troutdale for working families to live.

And if you look at aerial imagery or Google street view, the surrounding streets have dozens of empty parking spaces, since the Sheriff station across the street has off-street parking. There is not going to be a parking shortage here. https://goo.gl/maps/qCbssCjy9AJz4eNQ6

Erin Meechan

I live in the Troutdale area and I drive and I have affordable housing. I also have been part of the CAC for this Home Forward project. I hear the neighbor’s and business owners’ concerns about parking and access to basic needs.

We are turning the page for less carbon-producing elements, such as multi-modal mobility options. There is talk of a walking bridge and a bike hub. Trimet with the support of the business community proposes frequent service options to Portland and Gresham Max. I love the idea of scooters and pedestrian-friendly paths. Incentives for those that use other forms of transportation from Amazon and FedEx are already in place.

In these changing times it is difficult for folks to give in to what they are used to; and now is the time for action. Building more affordable housing and using the land more efficiently. I do believe there is a middle ground here and I trust that the people of Troutdale will come around to an agreement. This is part of a bigger plan of climate, health and wellbeing, and community engagement for the betterment of ALL the stakeholders. People don’t like change, but they do adapt when change happens. This is not just a desire for Home Forward to add to its portfolio, this plan is taking the right direction for equitable, efficient affordable housing -a human basic need for communities to thrive and grow in the present times.

Michael Andersen

Erin, thank you for your thoughtful comment. I hope you are right that a good solution can be found!

I didn’t get into the walking bridge you mention in the article above because it’s complicated to explain, so I’ll ask here in case you or someone else sees it: are you confident that there’s actually room on the site for a walking bridge that’d have a usable slope to it? Is there a plan to pay for it other than to attempt to get Home Forward to prioritize it over additional homes?

Erin Meechan

Thank you for your response Michael, and to be honest I do not have the answers about the walking bridge. What I do recall is that the feasibility assessment is about half of the cost of the actual building of the bridge. That is a steep bill and funding is very much of a concern, rightly so.