I wrote a couple of provocative blogposts last week (including one that went careening around the Internets and became my all-time most popular post). They elicited reactions ranging from the mildly inquisitive to the genuinely spittle-flecked. Good times!

But while I always welcome an argument—even a heated one—I was chagrined to learn that many readers misunderstood my intended point. That’s usually the author’s fault, as it was this time, and my post titles didn’t help matters.

So, I’m going to clarify a couple of things now:

- While it’s true that the biggest fuel savings by far can be found at the bottom end of the fleet, I don’t think that 18 mpg minimum is an acceptable stopping point for conservation. We should aim for much higher fleet averages.

- While it’s true that the there’s a bigger fuel consumption difference between 15 and 18 mpg than there is between 50 and 100 mpg, there is, of course, an even bigger difference yet between 15 and 50 (or 15 and 100). It’d be terrific if 100 mpg cars became commonplace.

- On the other hand, it’d be even more terrific, perhaps, if cars just became less commonplace than they are now. I didn’t say this earlier, but I should now: from the perspective of fuel conservation, we can also do other things besides vehicle efficiency standards. I think it’s of paramount importance to reduce driving too.

All that said, the surprising math of mpg clearly shows that once we get above 50 mpg or so, the fuel conservation returns diminish very substantially. That much is not debatable.

On the other hand, my interpretation of that mathetical fact is debatable. Here’s what I think: super-efficient future cars would be nice, but our climate’s future does not depend on big automotive technological breakthroughs, or on giant R&D investments. We can do it now.

I don’t know about you, but I take the mpg math to be tremendously good news. The biggest reductions in fuel consumption—and the biggest benefits to the climate—come from doing stuff we already know how to do. We should make conventional low-mpg cars more efficient. And we should support lots of alternatives to carbon-intensive transport.

[Updated 5:20] The bad news, on the other hand, is that we must actually do things now to support carbon alternatives. We’re not inventing our way out of this fix. And anyway, the perpetually right-around-the-corner vehicle breakthrough probably wouldn’t really accomplish very much—at least not compared to just making our existing SUVs a little more efficient. So, we have to roll up our sleeves, redesign our communities and lifestyles, and meet our climate goals with the tools we have right now.

Finally, here’s a tidbit to get comments started:

You save more fuel switching from a 13 to 17 mpg car than switching from a 50 to 500 mpg car.

Given that, where do you think our priorities should be?

Math and charts are below…

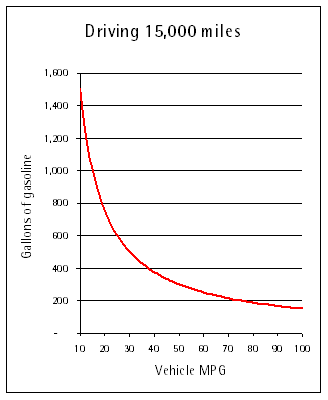

Miles-per-gallon math is pretty counterintuitive. You can find an explanation here and you can check my math (and do some of your own) here (xls). For some people, this chart helps:

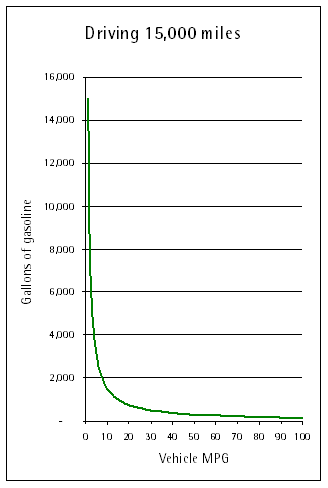

[Update 12/27] And for commenter barry, here’s a chart showing the same information, but this time scaling from 1 to 100 mpg. This really sharpens the importance of low-efficiency vehicles:

barry

The average lifespan of a car is 145,000 miles which currently is over 13 years. If you drive less than average, the lifetime expands outwards to decades. For example, IPCC says we need cuts of 25-40% below 1990 in next 12 years. Kyoto nations agreed to this at Bali. USA will too soon. In USA that is more like 33-50% from now. If people have to reduce driving 33% in existing cars in 12 years the average lifespan of these cars will go 18 years. Anyone buying a 17 mpg car now is going to be forced to drive it much less each year because of carbon taxes and carbon restrictions. It is very likely it will never be used for anywhere near it’s full 145,000 miles. We should not be telling people it is OK to buy a car that gets 17 mpg. It isn’t solving anything. It is creating a fleet of cars and trucks that will need to be restricted in their use. It’s a policy and infrastructure nightmare. In 20 years it will not be allowable to be driving a 50 mpg car like the Prius. In 30 years every car in the entire fleet will need to be zero-emissions. Since cars last 13 years in our drive-everywhere world already, that means zero-emissions cars must be the ONLY new vehicles sold in just 17 years from now…or less. Probably we need every car to be zero-emissions in just 15 years. We have almost none of these now.Where are these cars going to come from if we are still advocating 17mpg cars now? The emergence of 500mpg+ cars is going to take everything we have got. Oil companies and car makers are *NOT* going to build these if we keep buying 17mpg cars. No way. These are two of the biggest industries in history with lots to lose. Car companies make many thousands of dollars of profits from each 17mpg car and a couple hundred dollars profit from each sub-compact. Oil companies have a cash cow of billions of dollars they are fighting tooth and nail to protect. Where is the economic, and political incentive to build these going to come from? You say we should “support lots of alternatives to carbon-intensive transport” but we will never come up with support that can counteract the dollars put into buying new cars. We have to push as many of those new car dollars into low-carbon alternatives as we can.The only way we will be driving at all in 20 or 30 years is if we do everything we can to push for hyper-mileage, mostly-electric vehicles now. There is no breathing room for casually re-stocking our fleet with 18mpg or 20mpg or 30mpg cars. The thing most people fail to do when dealing with climate change is to do the carbon math backwards from the requirement of zero personal burning of fossil fuels in 30 years. This is what is required in order to meet the IPCC sustainable/survivable limit of 1 tonne per person in 40 years. Proposals to help solve climate change need to at least give a nod to how they will work within this timeframe and carbon ramp down. I don’t see how we get there based on the advice in this post. You say our climate future does not depend on cars with better mpg than we have now…but none of these can be driven in a low-emission transport future that is required. Are you saying forget driving cars? I can see that, but how realistic is that compared to developing zero-emission cars?If you think people will still be driving in 30 years, what is the route from advocating more 17mpg now to a 500mpg minimum for all new vehicle in just 15 years? Have i done the carbon math wrong? I’m lost on this one.

Eric de Place

barry, at the moment I don’t have time to fully respond to your very thoughtful comment here (but thanks for adding it to the discussion). So, for the moment, I’ll just note that most folks seem to agree that 80 percent reductions from 1990 levels are in order by 2050. Let’s assume that we want 80 cuts in the transportation sector (not a foregone conclusion) and that we further want 80 percent cuts in passenger vehicles (again, not a foregone conclusion). An 80 percent cut is like taking the current avg fuel efficiency of 20 mpg and raising it to an avg of 100 mpg. But that assumes that we keep driving just as much as we are today with fuels that are just as carbon intensive. If we postulate reductions in driving, whether from changing land-use patterns, high energy prices, or really simple stuff like carpooling, then we don’t need anywhere near 100 mpg avg. (After all, the simplest way to raise the efficiency of a car is just to fill the seats. Instead of averaging—what—about 1.2 occupants per car, we could average 3 or more. That’d more than double the effective fuel efficiency of vehicles.)Finally, here’s something controversial that I believe: the idea of the next-gen car has done a lot of damage—maybe more harm than the actual car will prevent when it gets here. I’ve personally been in policy discussions with well-meaning and influential people who want to keep expanding highways, or exempt transportation fuels from cap & trade, or don’t want to push density… And the reason? Almost inevitably, it’s someone told them that a 250 mpg car is right around the corner and then we won’t have to worry. The idea of the next-gen car—which I’ve been told for the last decade is “just about to arrive”—has been a dangerous palliative, allowing people to delay tough decisions and meaningful change. We don’t have time to wait. And, hey, for the record: all this stuff is Eric talking, not Sightline. That last paragraph especially.

morrison_jay

Eric,With Peak Oil coming, I can guarantee you an 80% reduction in CO2 emmissions from oil by 2050. It requires no laws and no changes in behavior by anyone. This reduction has already been mandated by geology and physics.The only issue is whether we start burning more coal or frozen methane hydrates and really screw up the climate after the oil production rates start declining.

SirKulat

OK, Eric. I’m gonna try to explain why I must (in a civil manner) dispute your contention that small improvements in fuel economy is a huge accomplishment, but I need your cooperation. First of all, your contention severely downplays the potential of Plug-in Hybrid vehicle technology. In order for the debate to be broadened, this potential must be elaborated upon. I wrote briefly of these benefits in the earlier article, but you didn’t integrate them into your argument. You have some understanding about walking, bicycling, mass transit and community building, but you do not (apparently) realize how the limited range of battery-only electric propulsion that plug-in hybrids offer leads toward fulfilling the goal of multimodal travel and transport:A plug-in hybrid vehicle, (which can be as small as a Prius or as large as a Ford Expedition) offers a limited battery-only driving range of 10-20 miles or so. Since the electric range is (or theoretically will be) much less expensive than any fuel, an economic incentive to drive less is created. In time, future development patterns create destinations that are accessable without having to drive; walking and bicycling become more viable travel options, the ability to structure mass transit becomes more practical, and the local economic development of community building being sought should follow hand in hand. Just improving mileage, whether 13-to-17mpg or 50-to-500mpg, goes furthest toward achieving the higher goal via plug-in hybrid. Added to this complex goal, the plug-in hybrid vehicle is a perfect technological match with rooftop photovoltiac panel solar power which will prove invaluable in an emergency, grid failure or utility price gouging. And the household with this back-up power supply has an excellent means to strictly monitor other household electricity consumption and further energy conservation. It bugs me to read such nonsense as, “becoming a vegetarian reduces more greenhouse gas than driving a hybrid”, or “hybrid battery production cancels environmental gains”, and your bit about SUVs, and so forth from the progressive community. The automobile industry should develop plug-in hybrid conversion kits and issue recalls, though they and Exxon and garage w/attached house suburban sprawl builders and financiers harumphiously disagree.

greveland

Y’all should read the post “For Fuel Economy, the Numbers DO Lie” by Jessica Branom-Zwick, and do some numbers on what geting the EPA to be honest would do to total fuel useage.

kstokes

Good show, Eric!Regardless of the specific math or focus here, I’m simply delighted we’re all turning now to exactly how our emissions reduction goals can be accomplished…fast.I’ve blogged many different aspects of the sustainable alternative transportation thang over on SusHI, and I thought I would chime in here with this insight from our discussions on Kauai.First, as a green economist, I’m a longtime advocate of ‘smart growth’, yet see little short-term gain coming from any ‘redesign’ of our communities. That is, even if all of our new development on this island were ‘smart’ and, say, at least medium density type projects, it will contribute a small fraction of our needed emissions cuts over the next 10-20 years.Nevertheless, from a systems dynamics perspective, where we hold a lot of different variables in play at the same time, I’m persuaded that some aspect of our driving patterns may be more readily alterable by simple things like a ‘Smart Jitney’. Apparently, a significant portion of our driving is short-distance, incidental pickup and delivery stuff, much of which could be readily substituted by a full-service jitney.So, one way to reduce vehicle-miles-traveled (VMT) is to switch away from many of our short-distance trips. My guess is that alt trans here gets us more emissions reduction than higher mpg (love to see someone take a stab at this math!). Note this also implies some near-term changes in our shopping patterns…and mebbe even Big Box/supermarket operations.Second, I’m persuaded that, at least on Kauai, it’s prolly smarter to switch engines than to switch fuels…especially since we have ample green electricity resources and are well-underway in our transition to all-green electricity. (Note: there may even be minerals for ‘energy storage tech’ laying on the floor of the ocean surrounding our island…)On the one hand, when we do the math on, say, biofuels, it’s not obvious that’s a smart move for all of our island’s ag lands.On the other hand, we should prolly make distributed generation part of our energy transformation…and this will engage virtually every household in corollary energy generation initiatives. Either way, I’m also persuaded that we need much more location-tailored tools for assessing the ‘ecological footprint’ of our transformation options…so we don’t produce any more ‘oooops’ stories…We’ll get to all these specifics in due course. For now, IMHO, we all need to work harder on changing how we think…learning to hold all three spheres in our minds at the same time (addressed here), and explore all the vicious/virtuous cycles we can imagine…’til we’ve got a much better sense of how our human support system functions.

barry

Hi again Eric,I’m glad to see the “future emissions math” in your comment. A couple points about 80 by 2050. First that is 80% of 1990. Emissions today are about 20% higher than 1990 in USA. So we are pushing 90% cuts as a nation. Second the population is growing in the 60 years from 1990 to 2050. A lot. The US Census says that it is already up almost 20% and is growing 1% per year. So per capita cuts will in the 95% range.I just did the actual math for 2020 using the MINIMUM 25% national cut from 1990 that EU, Canada, Russia, Australia and others have already agreed to. When you take into account our increased national emissions and our increased population since 1990 you get minimum per capita cuts from today of 45% in 12 years. Consider Bush will do nothing so you lose a year until next President. Then it will take a year to create and pass legislation and have it start to impact emissions significantly. That leaves 10 years to cut 45% per person. Cars last 13 years on average today. The cars sold today at 20mpg average will be on the road still. Drive them 45% less and they will last 20 years. And so on. We have a real problem. Because we have waited too long to raise the mpg of the fleet, we will need to significantly restrict miles driven per existing car per year. The longer we take to get to high mpg for the fleet the more we will be forced as a society to restrict car and truck usage. American’s so far have not done that. I totally agree with you that the promise of the hyper-car is used as justification for more of the same. It’s been that way for decades, eh? It is misery. Also it is true that increased efficiency savings are usually gobbled up by more usage. You can see this clearly in the slight increases in airplane efficiency being massively overwhelmed by increased flying because of cheaper flights. So I definitely see the dangers of the hyper-car. The choice North American society is making right now…car purchase by car purchase…is how painful the 45% reduction in 10 years will be. If we buy lots of mid-low mileage cars and trucks and SUVs in the coming years we will have to restrict their use significantly somehow. That is going to be more painful than requiring people to buy very high mileage cars now. Also, the wealthier folks can just bail on their SUV and buy a hybrid when prices go up. The poorer half will be stuck with SUV-stuffed used car market that is near impossible to drive much. We already see this in action in our rural area. We will have a wealthy driving class and a further disadvantaged poorer class. If you go out 20 years you see the per capita emission cuts are so big, around two-thirds, that most flying and driving of even today’s very high mileage gasoline cars will be a real luxury for a few only.In 30 years we hit the end of all personal burning of fossil fuels. It’s not just cars that will face big cuts in usage vs today. It is all long-lasting fossil fuel consuming machines and appliances. Water heaters, home heaters, airplanes, boats, trucking, construction, cement, industry, military, agriculture and so on. Many of these are much more critical to society and more difficult to transition to alternative power sources than personal transport. Many have much longer lifetimes. One simple example: Boeing just announced the biggest year of airplane orders ever. But a single round-trip flight on one of these from Seattle to Hawaii or NYC produces more emissions per person than the average person will be allowed in just 20 years for all their direct emissions for a year. Planes last for 40 years. With flying restricted, cars will be more crucial to connected our far-flung families, friends and biz.Cars will prove to be one of the easiest things to change in time. But clearly they will not be easy. You are right that one part of the answer is to drive less and to drive with more people in each vehicle. But i’m pretty sure we need zero emission cars soon or face a very nasty and bitter political and social fight to rein in emissions.

barry

One more quick clarification. As a society we can meet the coming carbon restrictions either by:A: raising the national fleet’s mpg fast enough to allow close to current levels of drivingB: restricting miles driven per car per year to significantly less than nowTo hit 45% emissions reductions from driving in 12 years without significantly restricting car miles we need to dramatically increase mpg averages. Far more than even California is trying to do. Fleet turnover takes over a decade. New car production takes a decade. It’s fine to advocate for B only. But it is worth asking people whether they would rather be forced to buy a high mileage car now when they buy a new car…or to significantly cut back miles allowed to be driven in future. Ask your friends, co-workers and neighbours. Hybrid or being forced to drive their car less?Of course in 10 years we need to be able to buy even higher mileage cars than the (now 10 years old) Prius of today. Who’s going to build them in time and in sufficient numbers? As Al Gore often says, the necessary is far beyond what is seen as possible right now. But it is still necessary.