Takeaways

Roe will likely be toothless by summer, and for people in many conservative states, Roe is already dying a death by a thousand cuts.

Strong pro-choice states like Oregon and Washington can support women and families from these places by expanding abortion care and related transportation needs.

Overall need for abortions has been in steady decline for decades, and continued best practices in reproductive healthcare and contraceptive options can keep that trend going.

Find audio versions of Sightline articles on any of your favorite podcast platforms, including Spotify, Google, and Apple.

Editor’s note June 24, 2022: In the wake of the US Supreme Court reversal of the Roe v. Wade decision that protected a woman’s right to choose an abortion, we are reposting this article from Sightline fellow Valerie Tarico.

US federal protection of a woman’s right to abortion will effectively end in 2022. Even if the Supreme Court shocks close observers and does not kill Roe outright, it will surely remove the precedent’s teeth. What does this watershed change mean for Cascadians? First off, it is a backward step that will cause real harms throughout the region, and disproportionately so for people of color and low-income people. Planned Parenthood clinics serving Spokane, Pullman, and rural Oregon are scrambling to build capacity and find funding for a flood of uninsured women traveling from Idaho, Montana, and even Texas for abortion care. Without additional funding, says Karl Eastlund, CEO of the eastern Washington and North Idaho affiliate, they may be forced to reduce preventive care, primary care, and mental health services in order to meet the urgent need for abortion. Staff also are bracing for an influx of roving, re-emboldened protesters who, as clinics in red states close, can now redouble their focus on those that remain.

Given these developments, Cascadia’s standing as a pro-choice stronghold is more important than ever for people wishing to choose whether, when, and how they have children. It is some comfort, then, that even as the area must gird itself to serve more patients, six key facts and trends will reduce the impact of the US Supreme Court’s whims with regard to Roe.

1. Abortion rights and coverage will remain intact for OR and WA Cascadians

Much of Cascadia has robust legal protection for abortion as well as strong systems of care. In Cascadia’s most populous parts, essentially nothing will change legally post-Roe:

- Washington’s longstanding and broad protections for abortion rights began entering state law even before Roe v. Wade. The state also now covers abortion services under the state’s Apple Care healthcare plans.

- Oregon encoded Roe v. Wade into state law in 2017 and mandated insurance coverage.

- Even red-state Alaska has a constitution that specifically spells out a right to privacy, and restricting abortion access would likely require a constitutional amendment. British Columbia is, of course, immune to SCOTUS action, but for the record: It places no gestational restrictions on abortion, and a 1995 law creates protected no-protest zones around clinics.

Further progress is afoot with regard to abortion medication that patients take in the comfort and convenience of their own homes. In 2017, Canada nationally removed restrictions on the abortion medication Mifepristone. Research at the University of British Columbia confirmed that the medication can be prescribed by any doctor or nurse practitioner and taken at home with no decrease in safety. On December 16, the US Food and Drug Administration, citing similar research, made permanent a set of rules that allow medication abortion to be dispensed via telemedicine, improving access for women in rural areas and “healthcare deserts”—critical for many across Cascadia.

2. Roe’s protections are already weak at best for many women, including in ID and MT

Legal rights are meaningless unless people have the means to act on them, and federal abortion rights have failed to create a uniform landscape of access. Idaho has abortion providers in only 3 out of 44 counties. This figure is about to get worse: the fall of Roe will trigger an Idaho law that bans all abortions save for rape and incest.

But even today, mandatory waiting periods, bogus “safety” regulations, and consent laws have driven up costs and created insurmountable barriers for some women while forcing others to seek care across state lines, if they can afford to do so. In Montana, abortion is already severely restricted, with parental notification requirements for teens and felony charges for some later-stage procedures.

In sum, while the eight million in blue-state coastal Cascadia are not at legal risk of losing their health freedoms and the one million women in red-state Cascadia are, this has been increasingly true even with Roe in place. Thanks to other trends in service provision, however, these women do not have to go back to coat hangers or coerced childbearing…

3. Transportation networks and providers in secure states are ramping up to serve women who must travel for abortions.

Idaho and Montana are not so terribly far away from Oregon, Washington, and British Columbia. Today 20 percent of abortion patients at Planned Parenthood’s clinics in Pullman and the Spokane Valley come from Idaho. A small fund, Women in Need, already helps pay for travel to specific clinics in the greater Seattle area. The Northwest Abortion Access Fund does the same thing for women in Washington, Oregon, Alaska, and Idaho; and the Portland City Council recently channeled $200,000 to this group to prepare for any post-Roe surge in need.

Just so, a National Network of Abortion Funds connects women who need abortions with organizations that can help them with travel, lodging, or medical expenses. In California, Governor Gavin Newsom says the state may become a “sanctuary” for those denied abortion care in places like Arizona and Utah. Newsom convened a group of abortion advocates, providers, and lawmakers that has produced 45 recommendations for how best to serve any influx. When SCOTUS ends Roe, watch for similar steps by leaders in Oregon and Washington.

4. A network of international organizations support and supply people choosing at-home self-managed abortion

Aid Access, founded by Dutch doctor Rebecca Gomperts, offers medication abortion via online consultation. Medical professionals screen patients and either connect them with mail-order pharmacies or ship medication themselves. Videos and FAQs provide information on how to self-manage the at-home process. The total typical cost is $100–$200, and one Washington doctor said she was able to serve over 200 women monthly through this program.

Along the Texas border, activists in Mexico are likewise preparing to move medications to women who need them. The ease of medication abortion from across state and national boundaries may be one reason that abortions dropped less than opponents hoped (and advocates feared) after recent Texas restrictions went into effect. But for those who care about voluntary childbearing, that’s not the only good news.

5. Need for abortion has been in steady decline for decades

As various regions modernized family planning during the last half-century, reliance on abortion tended to decline. In the US, abortions per capita peaked around 1990. For decades, approximately 1 in 3 women had an abortion in her lifetime. Today that number is around 1 in 4 and still dropping. Advocates for Youth had to rename its abortion storytelling project from the “1 in 3 Campaign” to “Abortion Out Loud.”

Though restrictive laws likely have played a role in pushing this number down in some states, the main explanation for this drop in abortions is a broader decline in pregnancy, and unsought pregnancy specifically. For example, in Montana, teen pregnancy fell by over 40 percent between 1988 and 2013 (the latest available data). In Idaho, it fell by half.

The change appears to flow from both cultural shifts and a revolution in contraception—a transition from intermittent abstinence or withdrawal, to error-prone barrier methods and pills, to modern “get it and forget it” contraception delivered via IUDs and implants.

State-of-the-art contraceptive devices are so effective that they can make virtually obsolete the most common kind of abortion. More than 90 percent of abortions are first-trimester procedures that are motivated by mistimed and unwanted pregnancies. (The remaining abortions include those motivated by risks to the physical health of the mother, fetal anomalies, and sexual assaults, as well as those delayed because of financial or logistical obstacles.)

For upper- and upper-middle-class women, those early abortions are becoming a thing of the past. As one acquaintance put it, “In the 1980s, my mom took my friends to get their abortions. Instead, I’m taking my daughters’ friends to get their IUDs.”

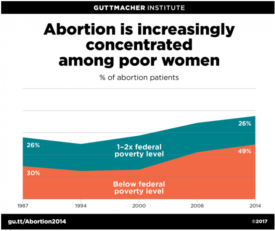

The challenge has been getting the same high-quality-but-expensive contraceptives to young women of color and women with lower incomes. Reasons include cost, insurance coverage, and institutional reproductive medicine’s history with these communities. Consequently, when it comes to preventing mistimed or unwanted pregnancies, there are deep chasms between haves and have-nots in terms of their freedom to plan their families as they wish.

6. Smart private-public partnerships are bringing top-tier contraceptives to more women

In 2014, Delaware teamed up with a nonprofit, Upstream USA, to transform contraceptive care across the state. Through Delaware CAN, professional trainers and university faculty taught primary care providers across the state to screen for pregnancy intentions, routinely asking women One Key Question during primary care visits: “Would you like to become pregnant in the next year?” (Oregon pioneered this practice, proactively asking women about pregnancy desires during routine doctor visits and then shaping care based on their personal pregnancy desires.)

Upstream taught providers to offer the full range of contraceptive options while respecting patient preferences and to provide IUDs and implants during that same visit rather than making the patient schedule a second appointment. They included birth-spacing conversations in prenatal care and, when desired, provided immediate post-partum IUDs and implants to new mothers. The result was that both unplanned births and abortions plummeted. There was no decrease in access to abortion care—simply a profound change in need.

A similar contraceptive access upgrade in Colorado had similar results. And it can work across the country. Today Upstream is working in Massachusetts, Rhode Island, South Carolina, and Washington State. Its partnership with Community Health Association of Spokane, which serves over 16,000 women annually, is showing others how it’s done.

Where Can We Find Hope Post-Roe? By Keeping Our Eyes on the Bigger Prize

The loss of Roe v Wade is a serious setback for Cascadia’s eastern states of Idaho and Montana, with more women being forced to travel long distances for abortions and the constant threat of punitive laws hanging over those who take matters into their own hands.

But Roe—and even abortion access more broadly—has always been a means to a higher end, and despite all, we can continue to make progress toward that end. The end goal of the abortion fight is that people should be able to form the families of their choosing at the time of their choosing with the partner of their choosing.

Opponents of abortion frame the procedure in the terms of a moral crusade; and in turning to counter them, we supporters too often forget that, for us, this never was about a specific medical procedure. We leap into the fray and match their battle cries with our own. But in the heat of clashing passions, we get drawn away from the ordinary clinical changes through which people quietly gain the freedom to form the families of their choosing, even in the midst of chaos and conflict. Improving medical practice along the lines of Upstream USA—asking better questions like One Key Question, developing and then offering better contraceptive technologies like get-it-and-forget-it IUDs and implants, upgrading medical practice to offer same-day, one-appointment care or in-hospital care for new parents who have just given birth. This strategy isn’t sexy. It gives no one an adrenaline rush nor a sense of moral righteousness. The emotions it arouses are neither triumphal nor apocalyptic. But these changes are powerful, and in the long run, that power is transformative.

Our prize is a world in which potential parents can chart their own course and children are born into families that are ready to welcome them with open arms. With that in mind, there’s a whole lot we can do to advance the cause, even without Roe.

Our region has the opportunity to double down on intentional parenthood as a path to greater opportunity, health, and human flourishing—in ways that have the side effect of making unmet need for abortion even more rare.