Here’s one way cities can help the owners of small homes: allow more building in backyards.

In fast-growing areas like the cities of the Pacific Northwest, small detached homes are no longer cheap. But they’ve always been the least expensive detached houses in the neighborhood. And as National Public Radio illustrated in a striking feature story last week, a foothold in the housing market can be a precious lifeline to the middle class.

“Fast-rising home prices in much of the US can raise a big question: To sell or not to sell?” reported Laurel Wamsley. “That decision can have long-lasting consequences for generational wealth—a particular concern for Black families, the result of America’s racial wealth gap.”

Oregon, especially its largest city, has been near the front of a recent movement in US housing policy: re-legalizing so-called “missing middle” housing like duplexes, triplexes, and fourplexes in low-density neighborhoods. Over the long run, this is good for both housing affordability (because more homes can be built in any given area, especially smaller ones) and social integration (because it lets exclusive areas gradually evolve into a mix of homes of different ages, sizes, and prices).

But for years, this progress has been dogged by several very good questions.

One: Triplexes are better than McMansions, sure. But to build them, aren’t you still going to end up knocking down the smallest and cheapest houses on the block?

Another: Will ordinary homeowners, especially those with less wealth and lower incomes, be able to take direct advantage of these new zoning options? Or will it all rely on developers swooping in, buying up lots, and swooping back out?

Related: A duplex usually requires at least one tenant. But how many people actually want to be small-time landlords?

Good news. There’s a pretty good answer to all three of these valid questions.

It’s right in the backyard.

ADUs require lots of cash on hand; lot splits don’t

If you want to see a block that could theoretically fit in a few backyard homes, stop by Southeast Stephens Place in Portland.

It’s one long residential block in East Portland’s Hazelwood neighborhood, a nine-minute walk from both David Douglas High School and a new rapid-service bus line that’ll open on Division Street in April. Ten modest-sized, mostly ranch-style houses line each side of the street between 135th and 138th.

The 20 homes on Stephens Place, all built in 1956 and 1957, would sell for $320,000 to $430,000 today. All are in fine shape, and it wouldn’t make much sense (economically or otherwise) to knock any of them down. In this part of town, $320,000 would be too much to pay for a house just for the sake of the land beneath it.

But as the decades go by, some of the buildings on Stephens Place will probably slip into disrepair, even if home prices in the area continue to rise. And because these homes have typical square footages for houses built in 1956 and 1957—right around 1,000 square feet—some of those might become ripe for either demolition or a high-end remodel that could double their prices without creating any additional homes.

There’s another issue on Stephens Place. Even if they wanted to take advantage of Portland’s current option for backyard construction, a small backyard cottage or “accessory dwelling unit,” most of the homeowners on Stephens Place don’t have a couple hundred grand to spare. New buyers on this block scrambled to find enough money to buy any home at all. In theory, a backyard cottage might be a perfect home for someone’s parent or sibling; in reality, where would the money to build it ever come from?

But if you could slice your backyard into a new separate lot to build a backyard house on, the answer is easier. Most of the money could come from an ordinary 30-year mortgage.

Infill without demolition makes social, environmental, and economic sense

For 20 years, Portland has been ahead of most other US cities in allowing and encouraging accessory dwelling units (ADUs). Since 2000, its ADU-friendly zoning reforms prompted a boom that has created a couple thousand new homes all over the city: converted basements, garages, garage attics, and custom-built backyard cottages.

Five months ago, Portland took a further step toward backyard infill with its “residential infill project.” Buried in a controversial and celebrated legalization of fourplexes and mixed-income sixplexes on almost every lot was an almost completely uncontroversial tweak to the ADU rules: instead of just one small secondary home, each home could build up to two.

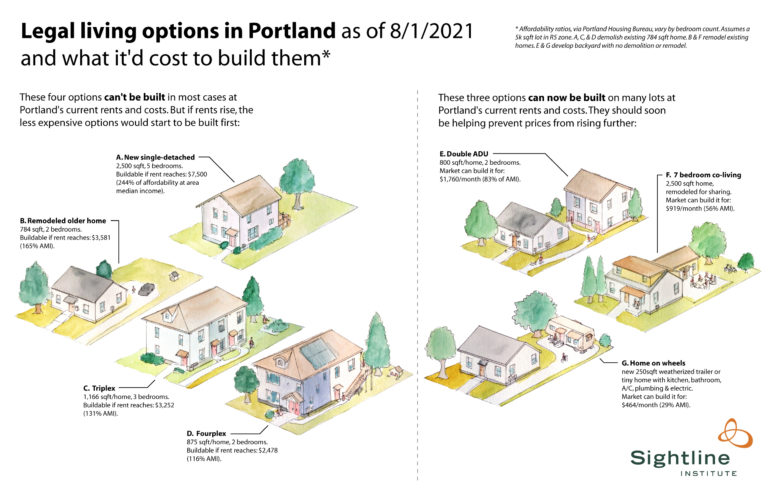

On the day Portland’s new zoning took effect, Sightline published a study that ran cost estimates for each of the new options to see which ones could potentially be built on a typical Portland lot in today’s housing market. Our findings are easy to summarize: The only options that can be built today on any remotely normal lot are the ones that don’t require demolition.

The infill options that can be built today are the three on the right in the image below—the three that involve putting stuff in the backyard.

Infill options that don’t require demolition are in line with the original vision of Portland’s zoning reform, which began in 2015 as a response to a spate of residential demolitions and set a general goal of legalizing smaller homes without greatly increasing demolition.

So what if Portland were to lean into the “build in the backyard” scenario, seeing it as a sustainability win-win-win? What options does the city have, and how many properties might be affected?

Let’s take the second question first.

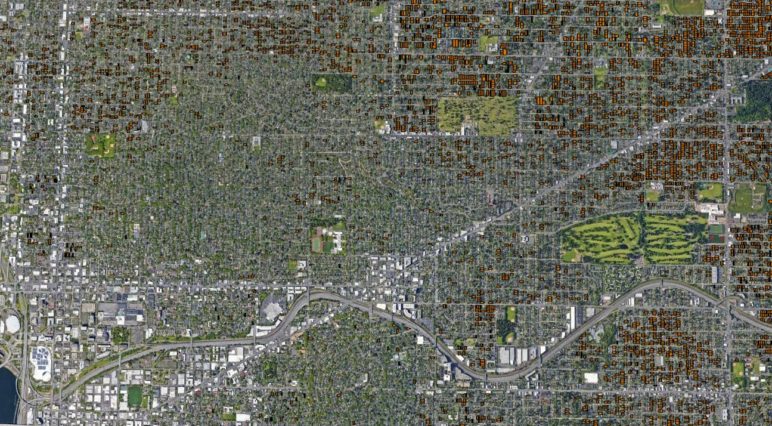

Portland has 23,486 lots with small detached homes, disproportionately in East Portland

With help from local firm Alta Planning + Design and the Metro regional government’s RLIS database, Sightline pulled together a rough estimate of the number of lots that are potentially available for backyard infill. We looked at every residential lot in Portland that’s between 2,300 and 20,000 square feet, doesn’t have wetland or major landslide risks on site, has a primary home listed as being between 100 and 1,067 square feet, and does not currently have any ADU on site. (Why exactly 1,067 square feet? We’ll get to that in a moment.)

Are all of these backyards buildable? Absolutely not. Everything depends on the exact size and location of the existing structure. Also, some of these public records haven’t been updated to reflect home additions, even though they’re supposed to be.

But, as you could see on Southeast Stevens Place, many of these backyards would be perfect for a bit of infill, if and only if their owners (a) would like to do it and (b) could figure out how to pay for it.

You can find these lots in every corner of Portland, though the richer an area is, the fewer such lots there tend to be. A slightly disproportionate share of these lots, 29 percent, sit east of 82nd Avenue, where lot sizes tend to be a bit larger and home sizes tend to be a bit smaller.

The small-house lots are marked in orange in the maps below.

Together, these potentially relevant lots represent 16 percent of all residential lots in the city, almost one in six.

It’s a lot of lots—a lot of potential new modestly sized homes in job-rich, transit-rich Portland. And a lot of Portlanders are probably interested in zoning rules that would create a path to more housing without tearing down a bunch of existing, smaller, older, and generally less expensive homes.

Two ways Portland could unlock more backyard housing

As it happens, Portland is at this very moment assembling a package of tweaks to its low-density zoning to complete its compliance with two state laws: House Bill 2001, which legalized duplexes, triplexes, fourplexes, townhomes, and cottage clusters statewide; and Senate Bill 458, which allows properties with this “middle housing” to be subdivided into multiple for-sale properties.

As the city’s planning commission weighs various proposals, here are two it could consider.

Warning: We’re about get a little technical.

1. End unfair ADU rules by treating properties with small houses the same as properties with big houses. This is a pretty quick and easy option. Portland has an old rule that says the owners of unusually small houses have to build extra-small ADUs.

To be precise, it’s three different rules, all of them with different versions of the same effect:

- If the main house on a lot has fewer than 1,067 square feet of floor space, then any external ADUs can be no more than 75 percent of the size of the main house.

- Any external accessory dwellings can cover no more of the lot than the main house does, even if the total lot coverage would still be less than is allowed for a newly built oneplex or fourplex.

- Accessory structures can’t cover more than 15 percent of any lot, even if the total lot coverage would still be less than is allowed for a newly built oneplex or fourplex.

These three rules emerge from a total of 130 words in Portland’s zoning code. But they make full-size external ADUs—that is to say, ADUs of up to 800 square feet—illegal on thousands of Portland lots. Specifically, they make full-size ADUs illegal on lower-cost properties, those that tend to be available to, and held by, Portlanders with less wealth. And, as noted above, these lots disproportionately sit east of 82nd Avenue.

It’d be technically very easy to strike out these rules that bind only the owners of small homes. But it’s also worth asking why they exist in the first place.

There’s an obvious political answer here: In 2010 and 2015, when the city last looked at those rules, “single-family zoning” was seen as politically sacred. Legalizing ADUs on every lot in Portland required rules to keep them unobtrusive, such as ensuring that they would be smaller than the main house.

Today, single-family zoning is illegal.

As Sightline wrote in a December joint letter with a coalition of nonprofit housing developers and service providers, some of whom are working to develop programs that create regulated-affordable ADUs in the backyards of low-wealth homeowners, the time for these unfair rules has passed.

2. Allow detached plexes to let people build non-ADU homes in their backyards. This option is more technically complicated. But if you want to benefit low-income homeowners, reduce demolition, and create more relatively low-cost housing, this has a much bigger payoff.

Little-known fact: Oregon’s “middle housing” law allows two full-size detached homes on the same lot to count as a “duplex,” three detached homes as a “triplex,” and so on. In fact, Oregon uses its statewide model code to recommend that cities allow detached plexes. Various cities are doing so.

If Portland were to follow suit and let a backyard home count as half of a “duplex,” that would have another huge benefit specifically for lower-wealth homeowners. They could take advantage of Senate Bill 458, Oregon’s middle-housing lot split bill, and finance construction of a backyard home simply by selling it to its future resident, who could take out a conventional mortgage to pay for the job. This would create low-cost “back lot” ownership options around Portland. It would democratize the development process by opening a simple, relatively attainable way for ordinary homeowners to finance backyard housing. It would create a new option for homeowners who currently face the agonizing decision of whether to abandon a home and neighborhood for cash. And it would mean that putting your backyard to better use wouldn’t also require becoming a small-time landlord; it would just require becoming a new neighbor.

Another way to legalize “back lot” homes, which would be odder on its face but potentially easier to write into Portland’s code, is to eliminate the minimum number of homes that Portland recognizes as part of a “cottage cluster.” This would allow two-home “clusters.” Because cottage clusters are also eligible for SB 458’s middle housing lot splits, it too could democratize the development process by letting homeowners sell the new home in their backyard to a homebuyer.

Bottom line: People who own small homes are better off when detached backyard housing is allowed

It’s easy to drown in the details here. But the fundamental situation is not complicated.

To bring home prices within reach and keep them there, cities in growing regions like the Pacific Northwest need to allow more relatively low-cost new homes. Portland’s rules for backyard homes currently favor bigger existing houses and preclude the option for many homeowners (and neighborhoods) with less wealth. Underused backyards are promising places to put more homes—especially if doing so makes it easier for ordinary and lower-wealth homeowners to take advantage of new “middle housing” zoning options without needing to move out of their home or neighborhood.

Like other Cascadian cities, Portland can choose among various paths to more backyard housing. The more paths the city chooses to open, the more Portlanders are likely to find their way home.

Thanks to Mike Sellinger of Alta Planning + Design for GIS analysis.