Takeaways

A few things to consider regarding Vancouver’s proposed Secured Rental Policy:

Most Vancouver renters were long ago priced out of the detached home market;

By relegating most new rental homes to busy streets, the City of Vancouver would double down on exclusionary zoning;

Arterial roads have documented health impacts that include higher rates of asthma, cancer, diabetes, and dementia, among other diseases; and

Vancouver City Council still has time to change course and re-legalize rental homes on quiet side streets.

The 2005 community vision for Vancouver’s Arbutus Ridge, Kerrisdale, and Shaughnessy neighborhoods recommends locating new apartments on or near arterial roads so that they can “shield, to some extent, adjacent single family homes from the noise of arterial traffic, …act[ing] as a buffer.”

Nobody’s home should be a “buffer” against traffic noise and pollution for someone else’s. According to a forthcoming report by the Canadian Association of Physicians for the Environment, the health impacts of exposure to traffic pollution include:

- Respiratory diseases

- Neurological decline

- Pregnancy-related and birth outcomes

- Cancer

- Diabetes

- Obesity

- Eczema

- Mental health impacts from noise exposure and stress

Underscoring these impacts, recent research from Harvard University found that pollution from fossil fuel combustion is responsible for an astounding one in five premature deaths globally.

And yet, Vancouver policy for at least the past decade has been to force new apartments onto busy and polluted arterial roads, even as they are banned next to parks and schools, and on quiet, tree-lined streets inside residential neighborhoods.

Nobody’s home should be a “buffer” against traffic noise and pollution for someone else’s.

Instead of planning for housing options in locations that maximize the health and well-being of residents, policymakers are mandating that people who prefer more compact, energy-efficient, and lower-cost homes can only live on traffic-choked arterial streets—and must suffer all the bad health consequences.

This November, Vancouver City Council will vote on the Secured Rental Policy, a proposal to legalize six-story rental apartments on busy arterial roads and four-story rentals on the adjacent side streets. It’s a much-needed reform to help address the city’s dire shortage of rentals.

Unfortunately, the proposal would do little to roll back the city’s ban on rental apartments in the vast swaths of leafy residential neighborhoods filled with detached houses on quiet side streets. Unless the draft Secured Rental Policy is amended to open up more of the city to multi-dwelling homes, Vancouver’s official position will remain clear: renters are fodder for protecting those fortunate enough to own detached houses on big lots.

Living Near Busy Roads Is Terrible for Your Health

The peer-reviewed research on living near traffic confirms what you might already suspect: living near traffic is bad for your health, and possibly much worse than you would think.

To cite one of dozens of examples, an Ontario-based study on the effects of air pollution found that living within 50 meters of a major road or within 100 meters of a highway reduces life expectancy by 2.5 years.

Children’s risk of asthma increases with exposure to traffic: one in five cases of childhood asthma in Canada can be attributed in part to traffic pollution, according to the Vancouver Coastal Health Research Institute.

On top of air pollution, recent research has identified a less recognized health risk: noise. A Danish study found that 11 percent of all dementia cases can be attributed to exposure to road traffic noise, and that a further three percent could be attributed to exposure to railway noise. While further research into the mechanism is needed, the release of stress hormones and disturbance of sleep are suspected causes. Similarly, an Ontario-based study shows that living close to heavy traffic is associated with a significantly higher incidence of dementia.

Together, these studies strongly suggest that separating people’s homes from the most acute sources of noise and air pollution could add years to residents’ lives, while reducing asthma in children and dementia in the elderly.

But you’d never guess that based on city actions. For example, Vancouver recently approved a new rental apartment on a truck route serving Western Canada’s largest port, while maintaining its ban on similar homes one or two blocks into the neighborhood.

The Secured Rental Policy

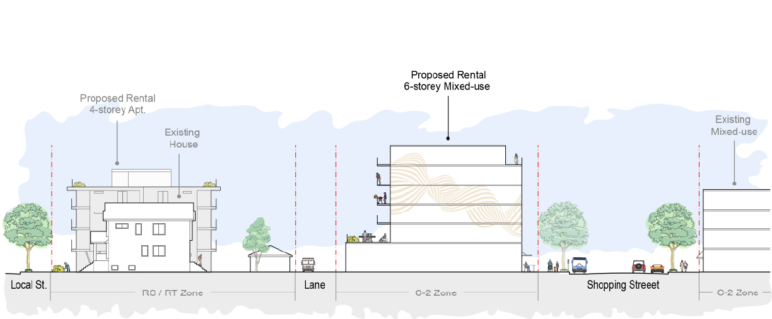

The Secured Rental Policy is a 348-page document that does two main things. First, it legalizes up to six-story, rental buildings on most city-designated arterials. Second, for blocks on arterials, it legalizes up to four-story rental buildings on the faces of the block lined by residential side streets. In commercial zones, these building types would be permitted outright—that is, no further city council approvals or hearings required.

At present, most arterial roads in Vancouver are zoned for commercial use, under “C-2” zoning, which allows four-story apartment buildings. But because Canadian taxes and regulations make condominium development more viable than rentals, new homes in these zones have mostly been condos. To encourage rental homes in C-2 zones, the Secured Rental Policy would permit up to six stories, while condos would remain restricted to four stories.

Along arterials currently zoned for detached houses and duplexes, the proposed policy would allow up to five stories of all-rental housing, or up to six stories with affordable housing included (one-fifth of the building offered at least 30 percent below market rents).

And on the side streets of blocks on arterials, the Policy would permit up to four stories of all-rental housing, with no affordability requirements. (Unfortunately, a consultant’s study projects little new four-story redevelopment because the proposal’s density limitations would make financial viability difficult to achieve.)

Arterial streets often host higher capacity transit lines, and Sightline Institute is certainly supportive of transit-oriented development, as we have shared here, here, and here. The issue at play is one of choice: arterial streets should not be the only places where families living on lower incomes should be able to afford.

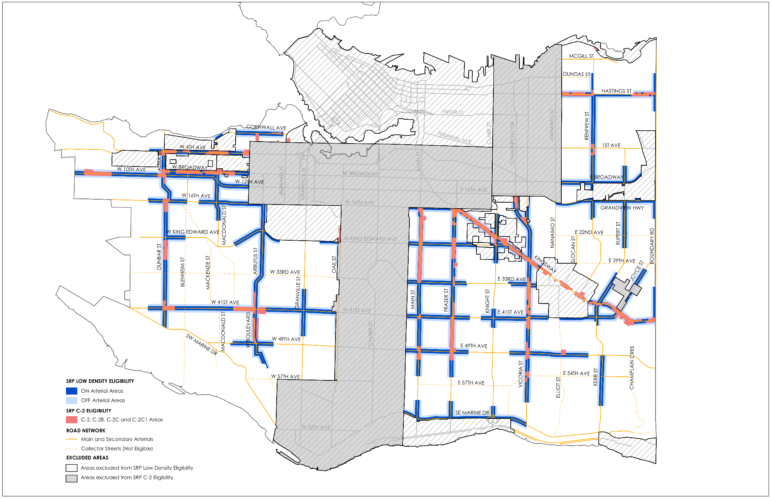

In the map below, the dark blue shows where six-story rentals would be allowed, and the light blue where four-story rentals would be allowed. Red areas would retain commercial zoning. Apartments would remain banned in the vast white areas in between.

(Note that the policy would not apply to areas that have recently completed or are undergoing their own planning process, shown in grey. Some of these plans will or already do include some limited provision for off-arterial rental homes, though all of them provide for the highest densities on the busiest roads. Also, the Secured Rental Policy does not cover the Squamish Nation’s Sen̓áḵw, a waterfront, 12-tower, minimal-parking, rental project that is on reserve land beyond the reach of Vancouver’s zoning code.)

Click image to enlarge

Vancouver approved an earlier version of the Secured Rental Policy in November of 2019, although no actual rezoning resulted. City staff noted at the time that rentals were concentrated on arterial streets, and that this “created an inequitable environment, where renters have limited housing choice.” Accordingly, the 2019 proposal called for expanding rental apartments into lower-density areas, and specifically, would have legalized rentals on most block faces within 150 meters of an arterial road.

In March and April of 2020, however, staff encountered significant opposition to rental apartments in lower-density areas. Opponents were specifically concerned about the Kitsilano and Point Grey neighborhoods, on Vancouver’s traditionally wealthier west side, where concerned neighbors have referred to building rental homes as “dropping the ghetto on Kitsilano.”

When the Secured Rental Policy returned to Council for implementation in June of 2020, council deferred and delayed any rezoning by a vote of 6-5, sending it back to staff for more consultation. The punt back to staff was supported by Councilors Bligh, Carr, Fry, Hardwick, Swanson, and Wiebe. Councilors Boyle, De Genova, Dominato, Kirby-Yung, and Mayor Stewart opposed the delay, citing the need for faster action on getting more rental homes built.

Finally, this November, Council will vote on rezoning changes under the revamped, modestly scaled-back Secured Rental Policy.

Vancouver City Council Could Allow Rentals on Quiet Streets

Most Vancouver renters were long ago priced out of the detached home market. Then they were priced out of the condo market. And now, the city’s zoning laws mandate that most new rental housing gets built in undesirable locations, unfairly exposing apartment-dwellers to the increased health risks that come from living on busy, arterial roads.

One of the legitimate purposes of zoning is to separate incompatible uses: to keep noxious factories and their emissions as far away from people’s homes and lungs as possible, for example. But zoning that bans apartments anywhere except busy streets does the opposite: it boosts the number of people exposed to health risks. On top of that, because renters typically have lower-incomes than owners, those increased risks fall disproportionately on those with less.

There’s a deeper political dynamic here, one that former Vancouver City Councilor Gordon Price has called The Grand Bargain:

From Expo 86 to the 2010 Olympics [Vancouver] has accommodated growth pressures on a small fraction of the city’s land, while avoiding the political unpleasantness of significant rezonings in built-out neighbourhoods, whether on the West Side, the East Side or even the West End.

Under this Grand Bargain, new housing is concentrated on busy streets, or on old industrial sites, while little to no change is permitted in neighborhoods of detached homes.

(An interesting side-effect of the Grand Bargain is it gives the impression that tons of homebuilding is happening in Vancouver. Both residents and tourists are likely to frequently pass through busy commercial streets and see all the development happening there. Meanwhile, the reality of the other side of the Grand Bargain—that most of Vancouver remains locked down for stand-alone houses only—is hidden away on the side streets and out-of-the-way neighborhoods.)

In the 1960s and early 1970s—before the Grand Bargain—Vancouver built large numbers of rental homes on quiet streets throughout residential neighborhoods. Some of these are the three-story, wood-frame apartments that house tens of thousands in Grandview Woodland, and Mount Pleasant. In the West End, even rental towers are commonly and pleasantly situated on local side streets. These examples provide much-loved local models for off-arterial rental housing that we could adopt and adapt for the 21st Century.

The city’s goal of advancing “transformation of low-density neighbourhoods to increase supply [and] affordability” was formalized in the 2017 Housing Vancouver Strategy. After countless hours of consultation, consideration, and deliberation, the 2021 Secured Rental Policy, while better than nothing, falls far short. The lines between “more consultation” and predatory delay are becoming increasingly blurry, as Vancouverites wait year after year for real action.

The underlying reason that Vancouver’s zoning laws confine renters onto polluted roads is that many homeowners in detached house neighborhoods prefer it that way. And by retaining this exclusionary zoning, Vancouver’s policymakers are discriminating against renters.

This November, Council could easily change course and re-legalize rental homes on quiet side streets, where the air is cleaner and it’s easier to get a good night’s sleep. Vancouver renters deserve nothing less.