For more than a century, the people of the United States have been locked in a game of cat and mouse with the forces of separation and segregation.

In 1917, the US Supreme Court banned explicit racial zoning but allowed zoning that banned apartments or duplexes. Within a decade, bans on these lower-cost housing types, which were theoretically race-blind but effectively locked out poorer people, had become popular in cities’ richest areas. In 1948, the court also struck down private contracts that required homeowners to sell or rent only to people of certain races. In the years that followed, duplex bans crept outward from those richer parts of town to cover most of the land in American cities. Here in Oregon, a 2019 state law has offered the next twist in the endless chase: duplex bans are currently being lifted in urban areas across the state.

In Portland, 2021 might go down in history as the beginning of the next phase of economic and racial segregation—the year that bogus “historic districts” replaced exclusionary zoning as the easiest way for a wealthier, whiter subset of the population to legally block change, diversity, and growth.

If that happens, here’s how it’ll work: a series of interlocking national, state and local rules will give a group of landowners in an area the ability to essentially override zoning without sign-off from a single elected official.

Not every landowner in the proposed district would need to agree; in fact, not even a majority of landowners would. No one who lives outside the district would get a vote at all. Even tenants who live in the district would be completely locked out of the decision, simply because they don’t own property in the right place.

If Cascadians are really unlucky, this abuse of historic preservation might become a model. Similar measures could spread to other cities and states in the coming decade, a new undertow beneath the country’s rising tide of zoning reforms.

There’s a fairly simple way to escape this future, at least in Portland. It just depends on a vote of its five-member city council in the year 2021.

landowners can create National Register districts with zero democratic oversight

On Wednesday, Nov. 3, Portland’s council will take up a proposed reform to its rules governing historic districts. On their face, the changes make sense. They’ll create new criteria for preserving places associated with queer Portlanders, indigenous Portlanders, Portlanders of color. They’ll clarify the process for creating, editing, and removing local historic districts.

And, crucially, the proposal will remove some of the most annoying things about living in one particular type of district: a district on the National Register of Historic Places. In those districts, adding solar panels to your roof or swapping in new windows will no longer require tight restrictions and big fees. Tearing down your old garage will no longer require a literal vote of city council.

This is fine. It’s nice when governments try to get rid of annoying things.

But here’s the trouble: Until 2021, the main force preventing National Register districts from spreading across much of the city has been the fact that it is annoying to live in a National Register district.

Unlike local historic districts (which will still have annoying rules), National Register districts don’t require a sign-off from city council to create. Under federal rules, the only way to stop the designation is to gather notarized objections from more than half the owners of land in the district. If that doesn’t happen, the proposal goes to a state historic preservation office that considers whether there’s anything adequately unique about the neighborhood and almost always decides that there is. (The office isn’t asked to consider any other factors; in fact, it’s not allowed to.)

What’s in it for landowners to get their neighbors’ property on the National Register? Two words: demolition review.

Faux preservationists openly admit demolition review is the key to overruling council-approved zoning

The U.S. federal government has developed the National Register district process since 1966 as a way to decide which buildings qualify for tax breaks and bronze plaques.

But in Portland, they’re a much bigger deal, largely because of demolition review.

Under Oregon law, any building identified as “contributing” to a National Register district—whether or not its owner agrees that their structure “contributes”—can never be replaced without the express permission of the city. (Portland’s current code goes further: demolition actually requires a direct vote of city council.) The real-world effect of this, though, isn’t actually to give more authority to city council. It’s to create a process so unpredictable that almost no one will ever risk pursuing a project that requires something as discretionary as demolition review.

Don’t take my word for it, though—ask the Eastmoreland Neighborhood Association. On September 20, they dedicated their neighborhood newsletter to two subjects:

- Attacking the city for re-legalizing fourplexes and mixed-income sixplexes. They claimed this will lead their neighborhood (current median home price: $626,000) to become less affordable.

- Calling for residents to support a new National Register historic district. They claimed a historic district would drive up home prices in their neighborhood.

“Houses retain and gain value in a historic district,” they wrote.

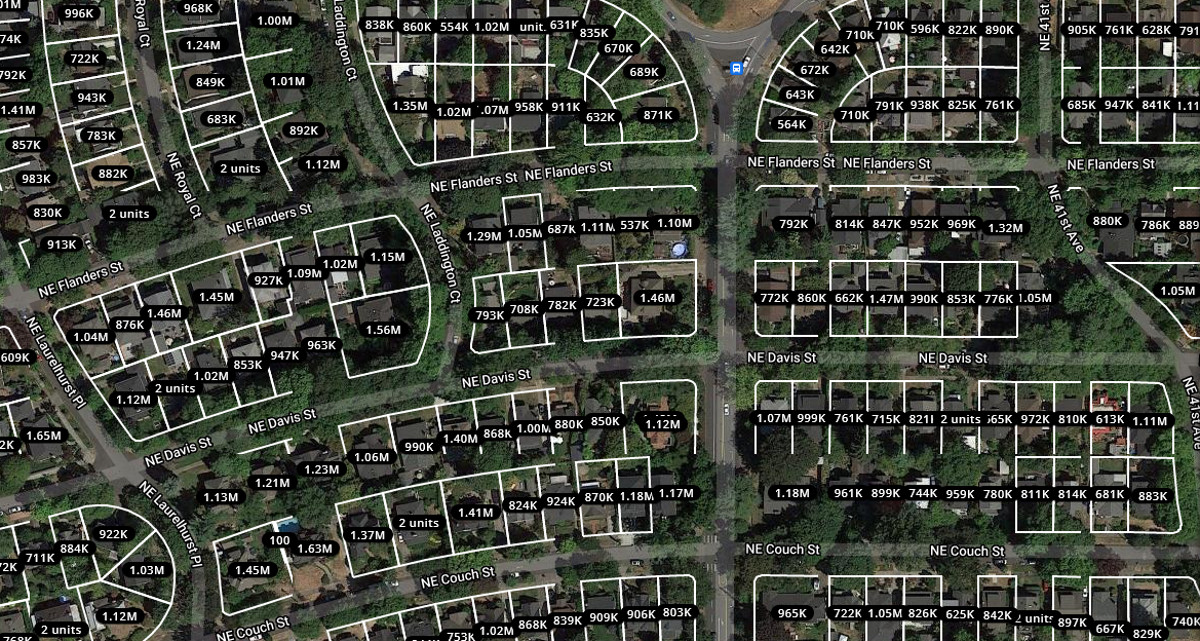

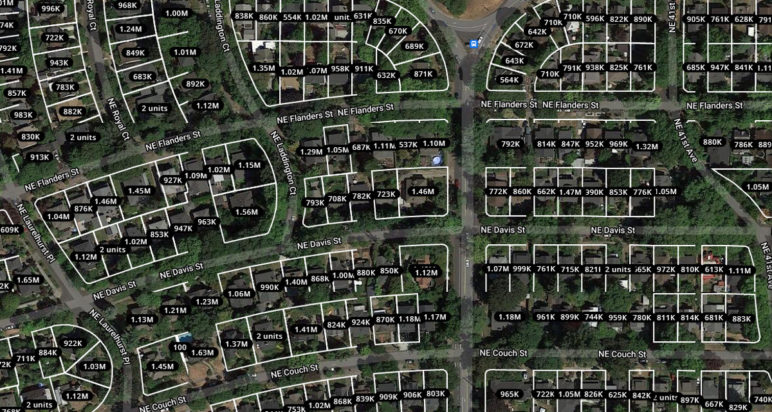

Or ask the Laurelhurst Neighborhood Association, backers of a recently approved National Register district in their area (median home price: $708,000).

“The city planners don’t like residents and neighborhoods taking the initiative to become National Register Historic Districts,” the neighborhood association wrote on its website last year. “The bureau can’t take away Laurelhurst’s National Register listing, but they can erode our demolition protections.”

This is 100 percent true. Another way to say the same thing would be, to paraphrase Jay Caspian Kang, that National Register districts allow small groups of landowners to wrest control of parts of Portland from the government of Portland.

Four years ago, when backers of a Laurelhurst National Register district were making a case to their neighbors in a 44-page report, I noticed that they dedicated thousands of words to describing how the plan would make demolition of the neighborhood’s homes “very difficult and rare” and zero words mounting any argument that Laurelhurst’s current buildings are actually uniquely historic.

These aren’t the arguments of people truly concerned about respecting Portland’s rich history. They’re the arguments of people looking for any available tool to keep the physical appearance of their neighborhood the way it is today—and to try to guarantee, as they also confess, that prices in their neighborhoods will keep going up and up and up.

National Register districts could easily spread across much of Portland with no council review

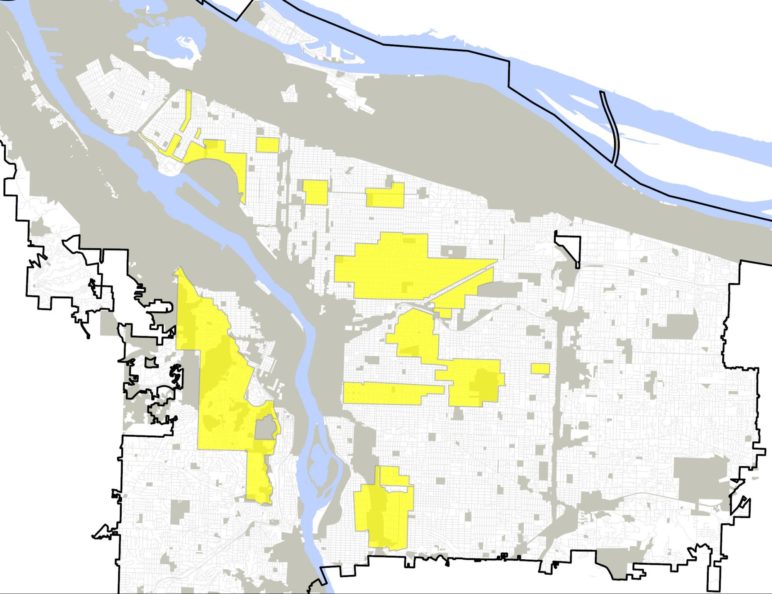

The first Portland neighborhoods to ban duplexes, from 1924 to 1959. Map by Neil Heller.

The stakes of this year’s proposed reform don’t end with Eastmoreland or Laurelhurst, though. The big risk is that these reforms will leave anti-infill agitators all over Portland with every incentive to go door to door collecting signatures in support of a new district—while also removing any major incentive for a homeowner to say “no.”

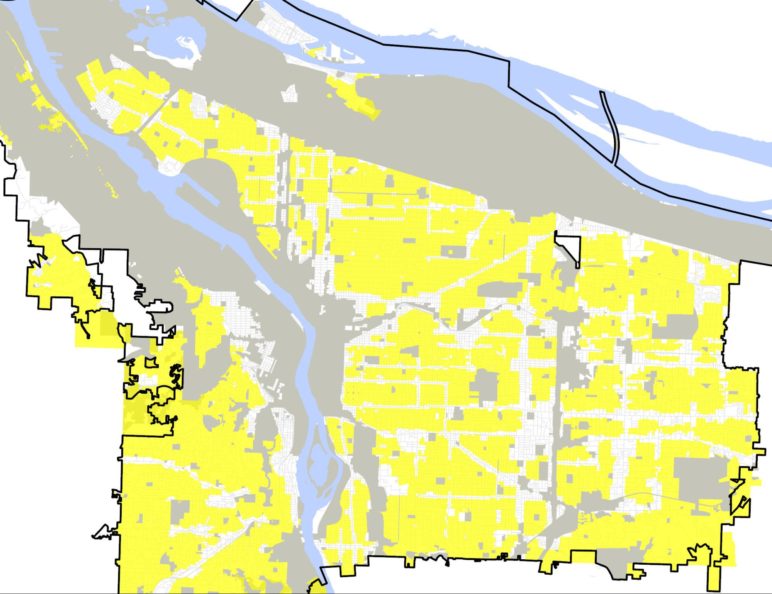

In 1959, Portland expanded duplex bans to most of the city. By 2018, this is what its low-density zoning map looked like.

Yesterday, Irvington; today, Laurelhurst; tomorrow, Eastmoreland; before long, Hillsdale, Mount Tabor, Johns Landing, Richmond, Sunnyside, Overlook, and beyond.

That’s almost exactly how duplex bans radiated outward from Portland’s most exclusive areas, almost exactly 100 years ago. Neighborhoods opted in, one at a time, until it presumably became a little embarrassing to not live in an exclusive place.

If homeowners have no material reason to object to historic districts, and tenants and housing advocates have no meaningful path to stop them, it’s not hard to imagine a 21st century sequel.

One recent exception proves the rule: Buckman, a majority-renter neighborhood with about 3,000 residents across the river from downtown Portland.

Portland is proposing to remove the thing that kept Buckman from becoming a National Register district

In 2011, a few dozen of Buckman’s several hundred homeowners seemed on track to create a new National Register district that would essentially overrule council zoning and mostly lock down 94 acres of land less than a mile from the largest employment hub in Oregon—downtown Portland. (A blog post from the Architectural Heritage Center was perfectly explicit about their motive: “This movement was in response to several redevelopment projects in Buckman that were whittling away at what was the first suburb in East Portland.”)

Their proposal was narrowly defeated by a campaign organized by a homeowner named Greg Moulliet. The main argument of the “Keep Buckman Free” campaign: owning property in a historic district would be annoying and expensive.

In 2012, Moulliet (who died in 2018) told the Daily Journal of Commerce that he was “not opposed to the idea of Buckman being a historic district as much as he is to the costs that come with it.”

Moulliet and his allies won. They found 348 property owners willing to sign notarized objections to the district, killing the proposal.

Since then, 10 redeveloped sites have added hundreds of additional homes to transit-rich, bike-friendly Buckman, a place where only about 40 percent of working residents drive alone to work. Buckman remains one of the city’s least expensive close-in areas, with a median income 30 percent lower than the city average.

None of this is to say that the expensive annoyances Moulliet railed against are worth preserving. It’s only to caution that they may be the main thing that’s been holding back a brand-new version of exclusionary zoning.

To protect democratic oversight, steer true preservationists toward local districts instead

One of the big ideas of Portland’s reform to its historic preservation rules is to give more relevance to local historic districts.

Today, undemocratic National Register districts receive Portland’s tightest restrictions. Local districts get looser ones. The Historic Resources Code Project (as it’s known) would reverse that. This makes good sense.

Unfortunately, the current proposal still goes out of its way to give anti-housing activists the power they openly yearn for—unpredictable, infill-repelling demolition review—without ever having to justify their neighborhood’s historic importance to city council.

The current proposal does at least include a carve-out for affordable housing. But it only applies to a type of affordable housing that almost nobody is currently building: small scattered-site plexes in low-density areas. Even with that carve-out, most anti-infill homeowners would know that, if they can get their neighborhoods designated “historic,” they’ll probably never end up living down the block from a new apartment building.

One way to fix this would be to roll back Oregon’s unusual requirements for National Register districts. Various state legislators have been chasing such a change for years, unsuccessfully.

But the City of Portland can act, too. It could meet state law without allowing National Register districts to essentially veto council-approved zoning. The key would be to create two new “approval criteria” for demolition of a contributing structure in a National Register district. Such a demolition proposal would be approved, city code could say, if demolition would be likely to facilitate an increase in either (a) the number of people living on site or (b) the number of regulated-affordable homes on site. To meet state law, there could also be an exception to the exception for buildings of truly unusual significance. These approval criteria couldn’t be used for a structure that is itself a National Register or local landmark (not just a contributing structure to a district) or to a structure that’s been provably unmodified since its construction.

The question of what outcomes are “likely” would be inherently subjective and discretionary. But the nature of the question would guarantee that the city’s discretionary answer would almost always be “yes.”

If proponents of historic preservation want stronger demolition review protections than a National Register district could offer, they would still have a clear path to doing so: convincing the city council to create local historic districts.

Such an amendment has been endorsed by pro-housing, pro-tenant advocacy group Portland: Neighbors Welcome and by Housing Oregon, a coalition of local affordable housing providers.

If approved, this amendment is not likely to end the century-long game of cat and mouse in Portland. Some more privileged people will probably always look for new ways to keep less privileged people from living nearby. And (with work and luck) governments will keep up the chase, too, finding new ways to stand up for the ability of all Americans to live more or less where they want.

But as the chase goes on, this could be a chance for the forces of freedom and integration to get one step ahead.

Robert F McCullough

Interesting inversion of the facts: the average cost increase in Eastmoreland after demolition of an existing home is 70%.

Michael Andersen

Robert, your neighborhood association’s newsletter is correct in that newly constructed homes are more expensive than otherwise comparable old ones, and that any homes demolished will tend to be the least expensive on the (extremely expensive) block. It would not be correct, however, to suggest that ending demolitions in our scarce housing market would somehow prevent the homes that remain from gradually getting more and more and more expensive. (Even as they fail to provide additional social value by increasing in quantity or, I suppose, size.) And it doesn’t make much sense to claim to be making an affordability argument against demolition while also advocating for a “historic” district on the grounds that it will further drive up home prices.

Paul gronke

There are more problems.

The “average” cost increase is not the best measure in a neighborhood with some extremely expensive homes. While I expect the median increase will also be substantial, using the average in this context is misleading.

In addition, we need to know what kind of homes are included in this 70% figure. Is it the small, 1 or 2 bedroom post war Cape Cods that dominate in the “Berkeley Addition” — an area that was explicitly drawn out of the historic district proposal? I like those small cute houses, and wish more people wanted to live in them rather than in a larger house. Regardless, including them in any calculation is also deeply misleading since they won’t be protected.

Eastmoreland is an extremely desirable, close-in neighborhood, and nothing in the neighborhood merits the use of the term “affordable.” I’ve tried to point this out to the association many times. At least now they use the term “relatively affordable” but still don’t seem to realize that “relative” in this context still means unaffordable to 90% of the income distribution. Continued use of the term it demonstrates precisely the kind of thinking (intentional or unintentional) that led to exclusionary zoning in the first place.

P.S. Michael, they also make “tree protection” arguments. Yes, that’s correct: creating historic districts and opposing the RIP is also sold as an environmental protection measure to stop “clear cutting”. It’s almost Orwellian.

M Brown

Laurelhurst resident here. The neighborhood used flowery language about preserving the neighborhood character and history when we all know the real motivation was to maintain exclusivity and further inflate home prices.

I think the City needs to head off the copycats before it is too late. 5% real estate transfer tax for contributing properties in a historic district. Phase it in so that existing homeowners will only pay it on the difference between original purchase price + 5 year capital investments and sales price. Second owners would pay 5% on full sales price, less capital investments.

Dedicate the funds to affordable housing.

If we are going to allow neighbors like mine to create wealth with these districts, then everyone should benefit.

Ian Crozier

How do historic districts in Washington state comapre? Yesterday a Washington state city planner suggested historic districts will pop up all over their city to combat missing middle infill.