Phasing out operations at Washington’s refineries would be good for the state’s climate goals, for the health of Puget Sound, and for the rights of native peoples in the region. But it would have profound impacts on the people who work at the facilities, and those effects would extend to nearby communities where the refineries contribute a lot to the economy.

The coming decades will bring increasingly volatile oil markets as well as promising boosts in energy efficiency, vehicle electrification, and a shift to cheaper clean energy. As demand for oil drops, Puget Sound refinery communities can plan ahead for a smooth transition—protecting workers, local economies, and the environment to build a thriving and resilient future. This article is part of a special series on the issue.

In this chapter, we will explore the significance of the refining industry for workers and local communities. It’s only fair to acknowledge at the outset of this chapter that the authors are white-collar knowledge workers who do not live near or work at the refineries. Our livelihoods would not be harmed by retiring them. Whatever comes next for Northwest refineries, it should include, explicitly, provisions to support refinery workers and create new jobs in high-wage industrial enterprises, including renewable energy. Left to its own devices, the energy markets have often resulted in unfair and unplanned transition, as happened to the coal miners of Appalachia. There is no reason we should allow the Northwest oil industry to treat its workers that way.

This chapter does not explore employment opportunities that may result from transitioning to a green energy economy. That topic will be covered in a subsequent chapter.

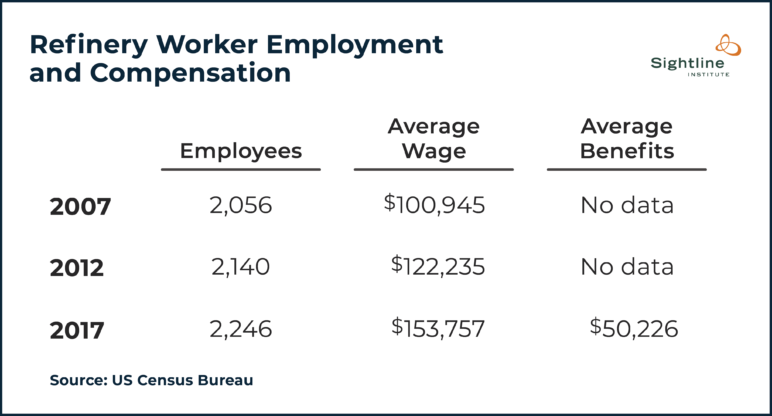

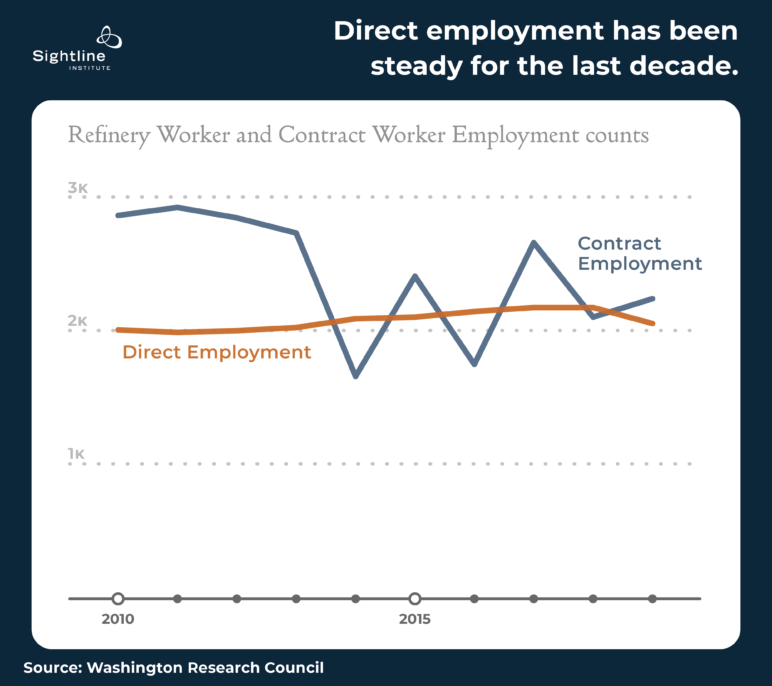

Employment at Washington’s five refineries has been steady for years. According to the US Census Bureau, going back to 2007, just over 2,000 workers have been employed each year in Washington’s petroleum refining industry. The Washington Research Council’s 2018 and 2021 reports on Washington’s petroleum refining industry depict similar, though not identical, employment figures. (WRC is funded in part by the oil industry and it uses self-reported employment data from refiners, but the numbers can be independently verified and are rigorously sourced.)

The WRC has regularly released economic impact reports for the refining industry going back to 2004. While direct employment has remained consistent, employment figures for contractors vary significantly year to year, depending on market conditions and maintenance needs. Between 2010 and 2019, on average 2,415 contractors were employed each year, ranging from a low of 1,656 contractors in 2014 to a high of 2,919 contractors in 2011.

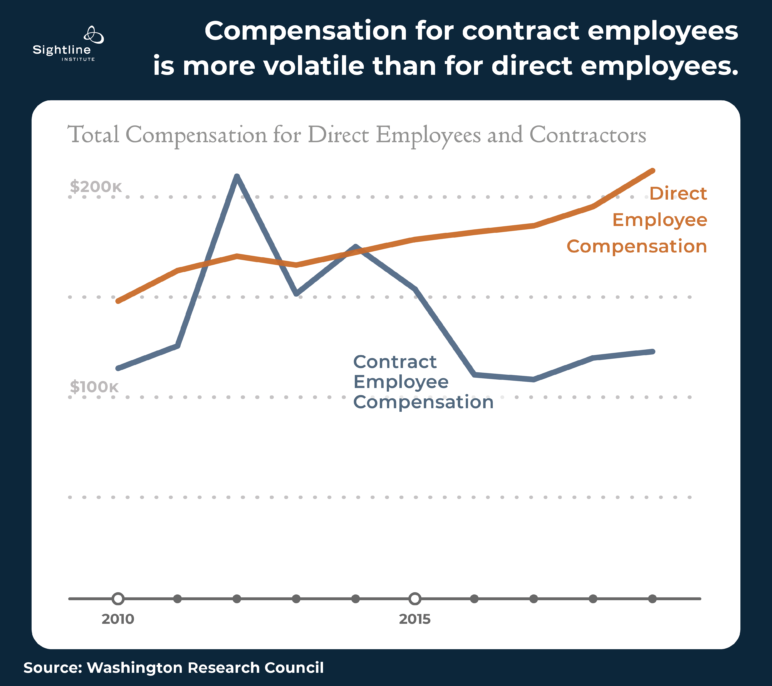

Refinery workers are, on average, very well paid. The census reports that refinery workers in Washington received an average salary of $153,757 in 2017, plus an average of $50,226 in benefits, for a total average compensation of more $200,000. The Washington Research Council reports slightly less generous compensation, with an average 2017 salary of $129,132 for full time employees (not counting benefits) and $108,900 for contractors. This inconsistency could be explained by the industry reporting different figures to the census and the WRC. Regardless, the data are similar enough to support the point that refinery workers, on average, are very well paid.

Compensation includes significant benefits, totaling $56,387 per employee in 2017. Full compensation, on average, amounted to $185,519 per full time employee. Benefits in 2017 accounted for 30 percent of the total compensation package.

These are good wages anywhere in the Northwest, and especially in Skagit and Whatcom Counties where the vast majority of refinery workers live. According to the Washington Employment Security Department, the average wage in 2019 for refinery workers in Washington State was $164,853, compared to an average of $52,308 in Skagit County and $49,662 in Whatcom County. Even entry level pay is good, starting at $35 per hour.1 For a fulltime employee, that works out to a $70,000 salary before benefits. Although the work requires specific skills, many positions do not require a college degree. According to the Political Economy Research Institute, 27.6 percent of Washington state refinery workers from 2010 – 2014 had a high school degree or less, 47.6 percent had some college or an Associate degree, and 24.8 percent had a Bachelor’s degree or higher. Refinery workers are overwhelmingly white and male. From 2010 – 2014, PERI estimates the refining workforce to be 16.7 percent non-white and 16.1 percent female.2

Refinery work is routinely dangerous. Consider the responsibilities for an entry level operator, a position which does not require a college degree, as described in a March 2021 job posting: “work near large, hot, high speed machines” and “work around chemicals.”3 Simply by working onsite, workers are exposed to a variety of harmful chemicals, including cancer-causing benzene. Plus, there are the rare but serious risks like the deadly 2010 fire at the Anacortes refinery that was then owned by Tesoro, which fatally burned seven workers onsite.

Dangerous mishaps are, unfortunately, an all-too-common risk for refinery workers who are sometimes at loggerheads with the oil companies that employ them. After the 2010 fire at the Tesoro (since renamed Andeavor) refinery, state and federal investigators blasted the company, calling it “complacent” about safety and issuing 39 citations of “willful” indifference to hazards at the site. Regulators slapped the company with a record $2.4 million fine, the highest in state history. And the safety violations that led to this loss of life were not the first discovered by Washington regulators nor the first discovered at Tesoro facilities elsewhere. In California, for example, Tesoro barred the gates to federal safety investigators after a burst pipe at a refinery sprayed two workers in the face with sulfuric acid. Though the workers were helicoptered to a hospital and treated for burns, the company called its employees’ injuries “minor.” The company went on to oppose union-supported efforts to have shareholders pressure the company into disclosing more information about its safety practices and risks.

The problem is broader than just one company, unfortunately. In 2011, the United Steelworkers and the AFL-CIO asked shareholders of several oil companies to allow the firms to disclose more information on their safety practices and accident risks. Yet all of the companies actively discouraged shareholders from approving the measures, making it more difficult for their investors and oversight agencies to get a full picture of working conditions and hazards.

Refinery workers are aware of both the constant, mundane dangers and the infrequent, explosive dangers of their jobs, and have a long history of striking for better wages and working conditions. In 1952, oil workers nationwide demanded better pay, agreeing to go back to work in return for 15 cent hourly wage increases across the board, as well as larger pay increases for overtime work. In 1969, unionized refinery workers across 35 states stopped working and demanded a 20 percent increase in pay, better benefits, and improved working conditions.4 At the Texaco and Shell refineries in Anacortes, the strike lasted over two months until the two sides were able to come to an agreement.5 6 Most recently, in 2015, workers at the Anacortes refineries again stopped working and demanded better working conditions, this time asking for “safe staffing” levels so workers would feel safe.

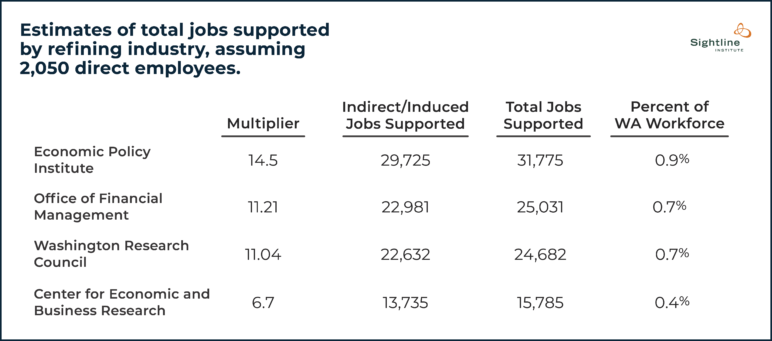

In addition to paying wages to its employees, the refining industry contributes to Washington’s overall economy through what economists call “indirect” and “induced” impacts. Indirect impacts refer to the effect that refining operations have on other industries when they buy products they need to run their operations and the impacts from selling their product to other industries to fuel their operations. Hiring contract workers is part of the industry’s indirect impact. Induced impacts refer to the effect that refinery employees have on the surrounding economy when they use their wages to pay rent, buy meals at restaurants, and more. The combined effect of the indirect and induced impacts on employment is referred to as the “employment modifier,” which denotes how many additional jobs are supported by each job in a given industry. The Washington State Office of Financial Management estimates the refining industry’s employment multiplier at 11.21. That is, for each full-time refinery employee the state believes that another 11.21 jobs are indirectly supported or induced.

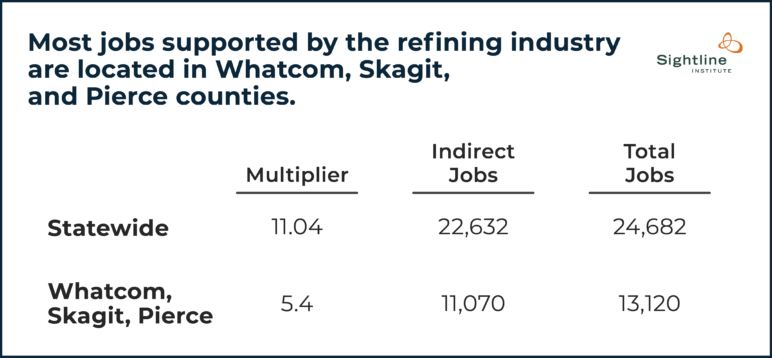

There is, however, some disagreement among economists regarding the size of the employment multiplier for the refining industry. WRC, in its 2021 report, calculated the multiplier for 2019 at 11.04 additional jobs indirectly supported or induced by the refining industry. Similarly, the Economic Policy Institute calculates the national employment multiplier to be 14.5 for the petroleum refining industry.

On the other hand, the Center for Economic and Business Research (CEBR) at Western Washington University, in its 2014 Employment at Cherry Point report, calculated the statewide refining industry employment multiplier to be just 6.7. Further, the CEBR report adapted OFM’s model to calculate the employment multiplier for the two Whatcom County refineries to be 5.4 within Whatcom County.

These employment multipliers provide a range of how many Washington jobs are supported by the refining industry. Calculated based on the 2,050 workers employed statewide in 2019, the indirect and induced jobs supported by the refining industry would be between 13,735 and 29,725. Given that total employment in Washington State in 2019 was about 3.7 million it would seem that the refining sector directly employs a little more than one-twentieth of one percent (0.05 percent) of the state’s workforce. Adding indirect and induced jobs, the refining industry might be said to support between 0.4 percent and 0.9 percent of Washington’s total workforce.

These indirect and induced jobs include everyone from gas station employees, agriculture workers using fertilizers, state and local government workers supported by refining industry taxes, and entertainment and restaurant workers paid by refinery employees’ disposable income. Some of these impacted industries, like agriculture, support jobs across the state while others, like restaurants, support jobs mostly near the refineries. Although the refineries have done tremendous harm to local indigenous communities (a topic we will explore in depth later in this series) it is only fair to acknowledge that some tribal members work at the facilities. And, through wages paid to their workers, they support many indirect and induced jobs at tribal business enterprises nearby, such as the Lummi Nation’s Silver Reef Casino Resort and the Swinomish Casino & Lodge.

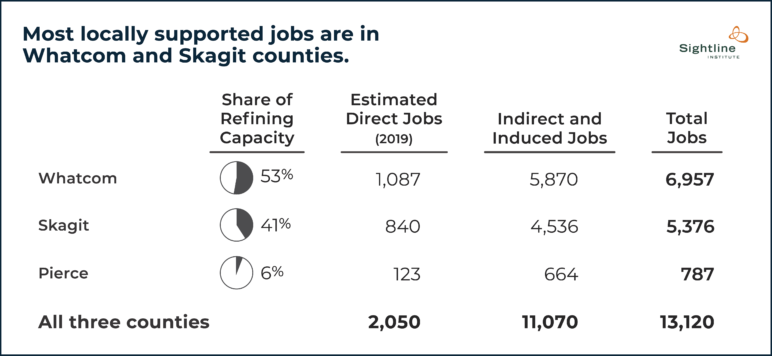

The indirect and induced jobs are not evenly distributed throughout the state. Gas stations and the employment they provide are ubiquitous, but other indirect jobs are less so. The refineries are all located on the shores of Puget Sound, with the four largest refineries sited in Whatcom and Skagit counties. Ferndale, population 14,000, is home to more than half the region’s refining capacity, while Anacortes claims 40 percent. Tacoma is home the smallest of the five refineries, accounting for slightly more than 6 percent of total refining capacity. It makes sense that a disproportionate number of indirect and induced jobs supported would be nearby. After all, that is where refinery workers likely spend much of their disposable incomes, and where refinery-adjacent businesses are often located.

How many local jobs (defined as in the same county as the refinery) does the refining industry support? Using the CEBR and WRC multipliers, Sightline calculates that the petroleum refining industry supports 24,682 jobs in Washington State. Slightly over half of supported jobs, 13,120, are located in Whatcom, Skagit, and Pierce counties. See the methodology section for the explanation of these calculations.

Employment at individual refineries is not publicly available but can be estimated based on refining capacity. Whatcom County refineries account for 53 percent of statewide capacity, so, in the absence of other data, we assume they account for about 53 percent of statewide refinery employment. Applying the local employment multiplier of 5.4 to the county employment estimate, we estimate Whatcom County refineries support a total 6,957 local jobs.

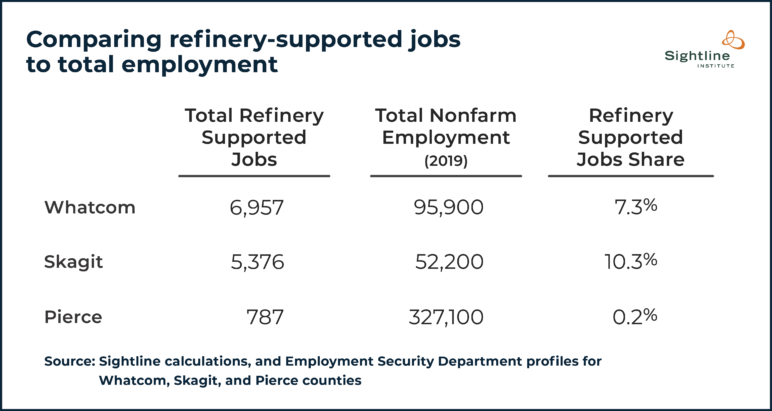

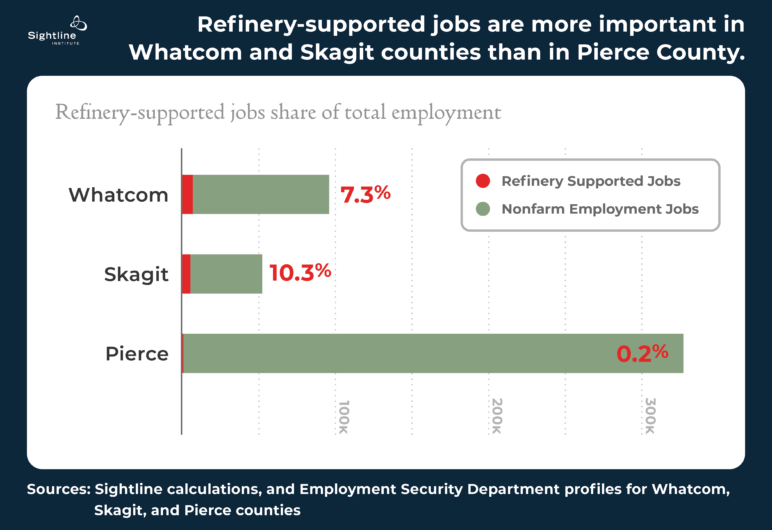

How significant are refinery supported jobs to local employment? Answer: it depends on the county. Pierce County is the second-most populous county in Washington and has only the US Oil refinery, the smallest of the five refineries. Accordingly, refinery supported jobs account for just 0.2 percent of total nonfarm jobs in the county.7 Refinery supported jobs make up a far greater share of total employment in Whatcom and Skagit counties. In Whatcom County, our calculations indicate that around 7.3 percent of nonfarm jobs are “supported” by the refining industry, and in Skagit County refinery-supported jobs account for over 10 percent of nonfarm jobs.

In summary, the refining industry directly employs around 2,000 employees. Refinery workers are well paid, making over $200,000 per year on average, including benefits. Another 22,632 jobs statewide are supported indirectly or are induced through economic activity, including about 2,000 highly paid contract employees. In total, the refining industry supports nearly 25,000 jobs statewide, about 0.7 percent of Washington’s workforce. These jobs are concentrated in Whatcom, Skagit, and Pierce counties. About half of the total jobs are located in those three counties, particularly Whatcom and Skagit, where the refining industry supports 7.3 and 10.3 percent of total county employment, respectively.

Later in this series, we will discuss what the future might look like for refinery workers. Many of these jobs would disappear if the refineries shut down, though it would presumably happen gradually over time, just as it did with the coal industry. There are numerous questions about how worker transition can happen fairly, whether through buy-outs or natural attrition or re-programming to focus on cleaning up the refinery sites and dismantling the physical infrastructure.

This article benefited from past research by Nick Abraham and David Kershner.

Methodology

To calculate the number of jobs supported by the petroleum industry, Sightline used the CEBR’s employment multiplier of 5.4 for local calculations and the WRC’s employment multiplier of 11.04 instead of the full range. There are several reasons for this decision. First, it is easier to use one number than a range and the WRC multiplier is a middle estimate. Second, the WRC estimate is the most recent calculation. Third, the WRC estimate is specific to Washington State and is nearly identical to the OFM estimate. Fourth, the WRC estimate, due to being funded in part by the industry, is likely the best-case estimate (from the industry’s perspective) of number of jobs supported. We are steelmanning the industry’s argument for economic importance. Lastly, the CEBR estimate local employment multiplier of 5.4 feels reasonable as about half of the total statewide multiplier. Local impacts may spill over defined county lines, but that is irrelevant to the broader point that economic impact is most significant in the immediate vicinity of the refineries.