The Portland Charter Commission is considering a lot of interrelated questions around city elections. One issue is the role of primaries. For most city elections, the primary is the election. If a candidate wins in May, then there isn’t a race in November. Primary voters tend to be older and whiter than general election voters, so ending an election in May gives less voice to younger and more racially diverse Portlanders. The Charter Commission could recommend an amendment to ensure that November voters always have a voice in city elections.

More voters would have a voice if all local elections were on the November ballot

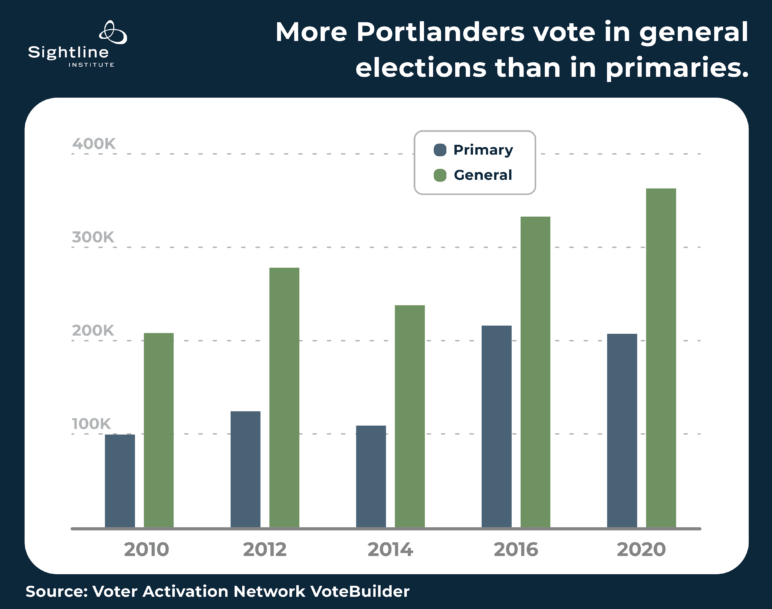

More Portlanders vote in the November general election than in the May primary—a lot more. In midterm years, November turnout is generally double the May turnout, and in presidential years, about 150,000 more Portlanders cast ballots in November. The outpouring of civic engagement in presidential elections tends to come from younger, more racially diverse voters.

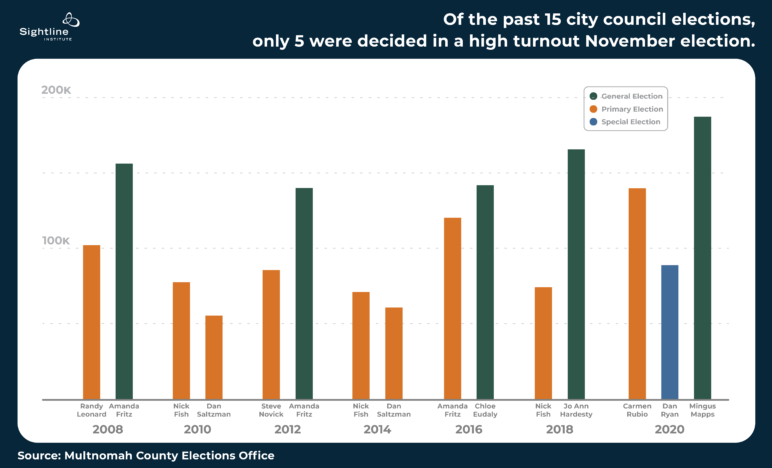

Yet in recent years, most city races end in May. Of the past 15 city council races (not including mayoral races), only five went on to the November election (green bars on the chart below), while the other 10 either ended in the primary (orange bars) or were in a special election (blue bar). The result is that the 100,000-plus voters—many of them younger and/or people of color—who cast ballots in November but not in May had no say in two-thirds of city council elections. Incumbents slipped into office with as few as 55,000 votes in the primary (as Dan Saltzman did in 2010), while new entrants had to fight for 180,000 votes in the general election to win a seat (as Mingus Mapps did in 2020).

Another interesting observation: in most cases, women candidates have been the ones who have to duke it out through November, while men have been more likely to be done campaigning in May. In the past 15 city council elections, Mapps is the only man who had to win his seat in a general election. All the other male commissioners—Randy Leonard, Nick Fish (three times), Dan Saltzman (twice), Steve Novick, and Dan Ryan— won their seats in a low-turnout primary or special election. The only woman to win in a primary was incumbent Amanda Fritz in 2016, and that was only after she had already won in the general twice (in 2008 and 2012). On average, women have had to earn more than 144,000 votes to gain a seat on the council, while men have won with an average of just 89,000 votes.

A proportional race in the general election would remedy this inequity, ensuring that all winners have to meet the same minimum threshold of votes from the same larger, more diverse electorate in November.

Send all top candidates to a proportional race in November

A primary is intended to cut down the field of candidates, not end the race. Portland could put the primary back in its place, using it to winnow the field and send the top candidates to compete in November. If the field doesn’t need winnowing, Portland could eliminate the primary entirely and shorten the campaign season, to everyone’s relief.

Here’s how it would work: let’s say Portland City Council were expanded from the current four to nine ten members, plus the mayor. All ten could run in the presidential year, but let’s say Portland staggered the races so that voters elected five members in midterm years and five in presidential election years. The primary could narrow the field to ten top candidates. If ten or fewer individuals declared their candidacy, the primary would be canceled, and all candidates would compete in the general election. If more than ten declared, then in May voters would see all the candidates and rank as many or as few as they liked. With no chance that the race would be decided in May, only that the field would be winnowed, the campaigns leading up to May would be less intense. The real campaigning would happen between May and November, when voters would see the top ten candidates and could rank as many or as few as they liked. The top five would win seats.

Eliminating or de-emphasizing primaries by ensuring that the real race is always in November would give more Portlanders a say in who sits on the city council.

A high-turnout election plus proportional voting would mean that more voters have a voice and candidates have more manageable campaigns

Some Portlanders might worry that pushing all candidates into a citywide race in November would drive up campaign costs. But even with a higher turnout, proportional elections would mean that candidates could run successful campaigns by targeting a smaller number of (possibly underrepresented) voters. Rather than every candidate running an expensive campaign trying to reach the same pool of voters, candidates could run smaller campaigns that pinpoint a particular group and dig deeper into an otherwise overlooked niche. Candidates could run smaller, less costly campaigns. Voters could be more likely to hear directly from a candidate, even if they are part of a group that too often get overlooked by the broader but shallower campaigns we have now.

Using the example described above, to win one of the five available seats in a presidential election year, each candidate would need to reach at least one-sixth of the voters. In the high-turnout election of November 2020, Mapps spent $500,000 to win 187,396 votes. If it had been a five-winner proportional race, he would have only needed 56,178 votes to win a seat. He could have run a smaller, more selective campaign to reach the tens of thousands of voters who were most aligned with him, rather than the scattershot campaign to win nearly 200,000 votes.

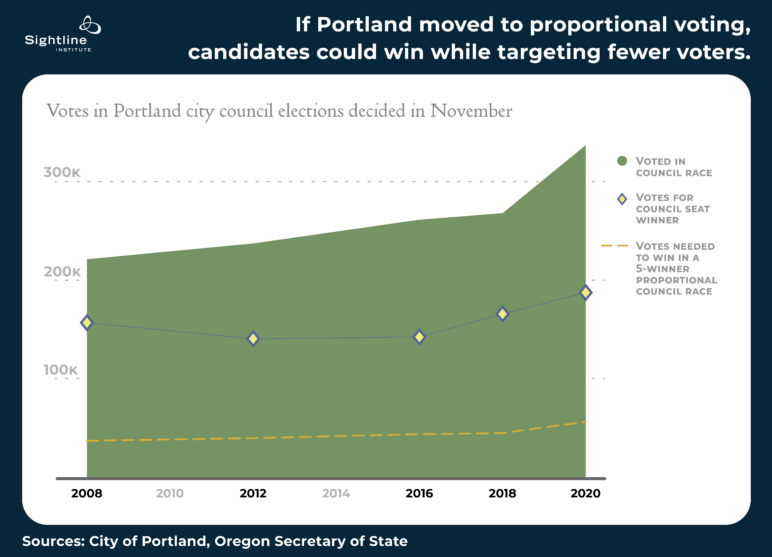

The chart below shows that more than 200,000 Portlanders vote in general elections in November (green area in chart below). From 2006 to 2020, only five city council races were decided in a November general election. Those five winners each garnered 100,000 or more votes (blue diamonds, below) to win one seat on city council. There are some community leaders who have looked at the “win number” of more than 100,000 votes (blue diamonds) and the accompanying fundraising requirements and felt they couldn’t raise the money needed to run.

Had those been five-winner proportional races, winners would have only needed to win 40,000 to 50,000 votes to win a seat (yellow dotted line). Portland’s public finance program, Open and Accountable Elections, has opened up the possibility of running for more candidates, but getting the “win number” down to the yellow dotted line with proportional races would open the field even further. With enough community support, more diverse leaders would have a shot at winning 40,000 votes, even without fat wallets at their disposal.

To give more candidates an opportunity to run small, targeted campaigns and give more Portlanders the opportunity to have a say in who sits in City Hall, Portland could de-emphasize primaries by moving to a proportional multi-winner race in November.