On July 19th, Oregon Governor Kate Brown signed one of the most aggressive clean electricity policies in the country. HB 2021, “100% Clean Energy for All,” aims to eliminate greenhouse gas emissions from the electricity serving Oregonians by 2040 with interim targets of 80 percent reduction by 2030 and 90 percent reduction by 2035. The bill also provides funding for small scale renewable projects and establishes labor standards. A complementing piece of legislation will subsidize low income rate payers and give social justice organizations more voice in utilities’ plans for a clean and equitable energy future.

The legislation was championed by the Oregon Just Transition Alliance (OJTA), an alliance of environmental justice organizations representing low income and BIPOC Oregonians who are most impacted by climate change. OJTA had been hosting statewide listening sessions with frontline communities and developing what a just transition might look like for years. When Khanh Pham, a leader for the organization, won the election for Oregon House District 46 in 2020, their policy goals found a home in the legislature. What resulted was the Oregon Clean Energy Opportunity Campaign, which consisted of these two electricity bills and the Healthy Homes bill (it also passed). Rep. Pham was a chief sponsor for all three bills. Nikita Daryanani, an organizer with the Coalition for Communities of Color, credited the bill’s success to the way the campaign centered the needs of those most impacted: “A lot of the policy components came from organizers understanding the communities that they worked with and their needs.” After two walkouts from Oregon Republicans over proposed cap and trade legislation in 2019 and 2020, the passage of these bills is a welcome development for Oregon, which is not on currently on track to meet its emission reduction goals.

The new targets build off of the Clean Energy and Coal Transition Act, passed in 2016, which required utilities serving Oregon customers to eliminate coal generated power by 2030. As of 2019, coal made up 27 percent of Oregon’s electricity but accounted for 73 percent of the sector’s greenhouse gas emissions. Natural gas, by comparison, produced 25 percent of the state’s electricity and contributed 26 percent of electricity emissions. Despite the stereotype that environmental benefits cost more money, getting rid of coal has already proven to be cleaner and cheaper than business as usual.

How utilities are planning to replace coal

Since Oregon lawmakers in 2016 required them to “kiss coal goodbye” by 2030, Portland General Electric (PGE), and Pacific Power, the two largest utilities in Oregon, have been planning how to fill the gap left by coal.

PGE provides about 34 percent of the power in Oregon, serving customers in the Portland and Salem metro areas. In 2019, its power mix was 42 percent natural gas, 19 percent coal, 12 percent large hydro, and seven percent wind. Its only coal-fired plant in Oregon, Boardman, closed its doors in October 2020. The Integrated Resource Plan (IRP) filed by PGE in 2016 generated major backlash when it proposed expanding its natural gas Carty Generating Station to fill an anticipated 561 megawatt gap left by closing Boardman, the last coal-fired power plant in Oregon. PGE scrapped the plan even before the Public Utility Commission ruled against it. In its 2019 filing, PGE’s preferred portfolio included additional investments in demand management, renewable sources, and energy storage, but no new gas-fired capacity.

Pacific Power provides about 27 percent of the power in Oregon and also serves customers in Washington and California. Its power mix is 57 percent coal (all from out-of-state plants), 18 percent natural gas, and eight percent wind and solar. Its parent company PacifiCorp, based in Oregon, also serves Rocky Mountain Power customers in Utah, Idaho, and Wyoming. Under pressure from a combination of Oregon’s rules, California’s emissions standards—which have effectively eliminated coal since 2007—and changing market conditions making coal more expensive than cleaner power sources, PacifiCorp is making major investments to change its portfolio. Its IRP submitted to the Oregon Public Utilities Commission (OPUC) in 2019 accelerated the retirement of seven coal-fired units. Of its twenty-four coal facilities that operated in 2019, sixteen will be retired by 2030, and another four will go offline by 2038. An analysis commissioned by the Sierra Club in 2018 found that 12 of PacifiCorp’s coal units were more expensive to operate than solar, and 20 were more expensive to operate than wind energy due to falling renewable costs. The new portfolio favored by PacifiCorp in their IRP estimated will likely save $300-$500 million over the next twenty years. A list of 19 solar, wind, and battery storage projects totaling 3,250 megawatts by 2024 was submitted in June to regulators for approval.

PacifiCorp’s next IRP will be published this month, and PGE’s is scheduled for 2022 along with the additional Clean Energy Plan required by this bill. Each company will also convene a Community Benefits and Impacts Advisory Group. The members must be representative of environmental justice communities and low income ratepayers. The group will publish a biennial report on energy burdens and disconnections for customers, opportunities to increase contracting with minority-owned businesses, ways to improve resilience during adverse conditions, and distribution of investments and infrastructure.

Consumer-owned utilities—a mix of 38 separate electric cooperatives, people’s utility districts, and municipal utilities across the state—produce a combined 32 percent of Oregon’s electricity. They get the vast majority (79 percent) of their electricity from hydropower, followed by 10 percent nuclear, five percent natural gas, and five percent coal. They are not required to submit plans to the OPUC, and the Clean Energy for All bill does not apply to them.

The cost of getting to zero

While both utilities have envisioned pathways to dramatic emission reductions, neither have sketched a path to zero.

In 2019, the utilities laid their plans for getting out of coal. But by 2022, they will need a plan for getting out of greenhouse gas pollution entirely by 2040. While both utilities have envisioned pathways to dramatic emission reductions, neither have sketched a path to zero. A 2018 study on Deep Decarbonization done by PGE explored a target of 80 percent reduction in greenhouse gasses from 1990 levels by 2050. PacifiCorp’s 2019 IRP planned for a 90 percent reduction from 2005 levels by 2050. Now, Oregon law requires it to achieve 100 percent reductions by 2040.

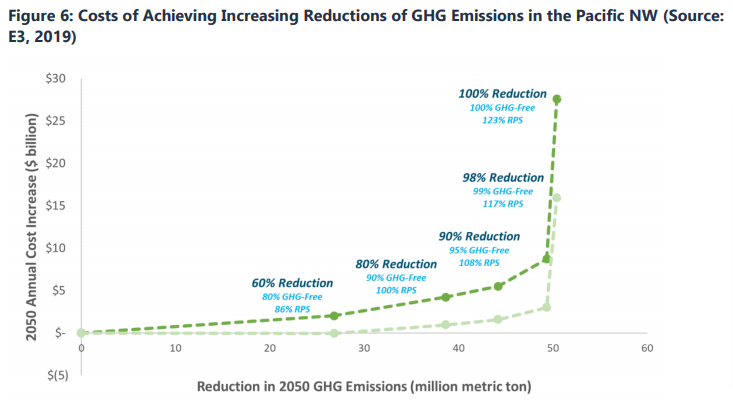

An analysis on low carbon scenarios by Energy + Environmental Economics estimated that the path to 98 percent reductions is relatively straightforward, but wringing that final one or two percent of emissions from the grid could get incredibly expensive. An additional $100-170 billion in investments would be needed to remove the last one percent of emissions from the grid. This cost cliff is due to the amount of renewables that would need to be built to meet rare peak load scenarios. The Energy + Environmental Economics (E3) graph below shows that Oregon can reduce emissions by 80 percent by building out enough renewables to meet 100 percent of an average load. But to get to zero emissions, utilities need to build enough renewables to meet 123 percent of average load, a much more costly endeavor.

Natural gas facilities have long been favored to meet peak load scenarios. On average, those facilities run at 60 percent capacity and are able to ramp up to full capacity when needed. In rarer situations, co-located natural gas peaker plants, plants that only turn on when demand is particularly high, ramp up to meet times of extreme demand. Building a zero carbon grid will require new renewable facilities and storage to lay fallow until needed. Peak demand energy generation has always been expensive, since facilities can only recoup their investments through a limited amount of hours, but falling battery prices are already upending the market. Still, time-limited batteries cannot yet fully replace the flexibility of generating additional electricity for longer periods of high demand. The Pacific Northwest is historically a winter-peaking system, but hotter and more widespread heatwaves are challenging the grid in new ways. In a call with shareholders in July, Portland General Electric disclosed that at the peak of the June heatwave, demand soared to 4,041 megawatts, beating their previous record set two decades ago.

Natural gas facilities have long been favored to meet peak load scenarios. On average, those facilities run at 60 percent capacity and are able to ramp up to full capacity when needed. In rarer situations, co-located natural gas peaker plants, plants that only turn on when demand is particularly high, ramp up to meet times of extreme demand. Building a zero carbon grid will require new renewable facilities and storage to lay fallow until needed. Peak demand energy generation has always been expensive, since facilities can only recoup their investments through a limited amount of hours, but falling battery prices are already upending the market. Still, time-limited batteries cannot yet fully replace the flexibility of generating additional electricity for longer periods of high demand. The Pacific Northwest is historically a winter-peaking system, but hotter and more widespread heatwaves are challenging the grid in new ways. In a call with shareholders in July, Portland General Electric disclosed that at the peak of the June heatwave, demand soared to 4,041 megawatts, beating their previous record set two decades ago.

Lawmakers are hopeful that trends in battery costs and future technology will work in our favor over the next decade, allowing utilities to achieve those last few percentage points with storage or other technologies that are less costly than Energy + Environmental Economics’ estimates. In case those don’t pan out, the Oregon Public Utility Commission is able to grant temporary exemptions to utilities to prevent cost increases greater than six percent of annual revenue, a clause intended to protect ratepayers.

Is there a role for “renewable” natural gas?

One option for getting to zero emissions by 2040 could be “zero-emission” natural gas. It already caused a stir in neighboring Washington state when Puget Sound Energy proposed relying on “renewable” natural gas – gas that is created as a byproduct of landfills and wastewater treatment—to reach its emissions targets. Washington’s 2019 Clean Energy Transformation Act (CETA) requires utilities to reduce greenhouse gas emissions to zero by 2045. Puget Sound’s first IRP since, released earlier this year, drew ire from environmental groups for proposing to add flexible capacity with “renewable” natural gas. Advocates argued that this gas is not even currently feasible to use in this way, lacking a clear supply chain and availability, and they worried that regular natural gas would be substituted as a backup fuel. Puget Sound Energy claimed it was the least-cost option to meet flexible capacity needs.

Technical feasibility aside, advocates question whether any form of natural gas is in the spirit of the law. A coalition of environmental organizations, headed by the Sierra Club submitted testimony, pointing out that potential methane leaks in natural gas pipelines are often unaccounted for. They also noted that methane is a powerful greenhouse pollutant and so damaging to the environment that, overall, natural gas may be just as damaging as coal. CETA defines renewable natural gas as a renewable resource, and a utility can have it in its portfolio and still be in compliance with the law.

Oregon’s law explicitly bans new fossil fuel facilities but has provisions for the Public Utility Commission to make exceptions if they can determine the new facility will only generate non-emitting electricity. This unfortunately leaves the door open for future renewable natural gas or carbon capture and storage proposals.

Investing back into community, and giving the community more power

Oregon’s “100% Clean Energy For All” bill establishes a new Community Renewable Investment Program. Oregon tribes, public bodies, or consumer-owned utilities can apply for funding for small scale renewable energy or resiliency projects up to 20 megawatts anywhere in Oregon outside of Portland. Projects could include solar power micro-grid installation for rural hospitals or cooperatively-owned wind farms. The Oregon Department of Energy will oversee the fund, which was allocated $50 Million in general funds to be spent over the next four years.

The labor standards included in the bill ensure that all people hired to construct or repower an Oregon energy project of 10 megawatts or greater will be paid the area wage standard and receive healthcare and retirement benefits. Employers need to make a plan to outreach, recruit, and retain women, BIPOC, veterans, and people with disabilities, with a target of fifteen percent of total work hours being performed by individuals of those groups. Employers must also have a workplace harassment policy and submit documentation of their hiring outreach including contacts to apprenticeship programs and union halls.

Oregon lawmakers also passed HB 2457, the Energy Affordability Act, which will give energy rate relief to low income customers, and was supported by a broad range of stakeholders. One out of every four Oregon households are energy burdened, paying more than six percent of their income to energy costs. The problem is most stark in rural Oregon. In 2018, over 40 percent of all households in Crook, Harney, Wheeler, Lake, and Malheur County were energy burdened. Current assistance programs reach less than twenty percent of eligible customers. To make energy affordable to them, the Public Utility Commission will try to narrow a $350 million energy affordability gap through direct rate relief and financial agreements. The law also funds $500,000 annually to organizations that represent customers who are low-income or members of environmental justice communities so that they can be compensated for their time to participate in Commission proceedings. Similar programs, frequently called Intervenor Compensation, already exist in California, Hawaii, Maine, Virginia and Wisconsin. An audit of California’s program in 2013 found multiple occasions where intervenors saved rate payers hundreds of millions of dollars, and brought more diverse interests including low-income and minority rate payers and environmental concerns to regulatory proceedings.

Oregon Clean Energy FTW

Together, these energy bills will significantly advance clean energy in Oregon while prioritizing environmental justice. For advocates, this work is far from over as these new laws enter rulemaking phases. When asked about next steps, Daryanani stressed, “Passing policies is just one part of the battle. We also have to make sure that they get implemented in a way that is true to what the community priorities were that helped pass the bills in the first place.”