Last time, I chronicled France’s success at boosting homebuilding in greater Paris. This time, I look at the industrial world’s laggards in abundant housing.

Might the boldest new examples of leadership for abundant, low-carbon housing come from two of the worst places in the world at providing it—and from opposite ends of the political spectrum?

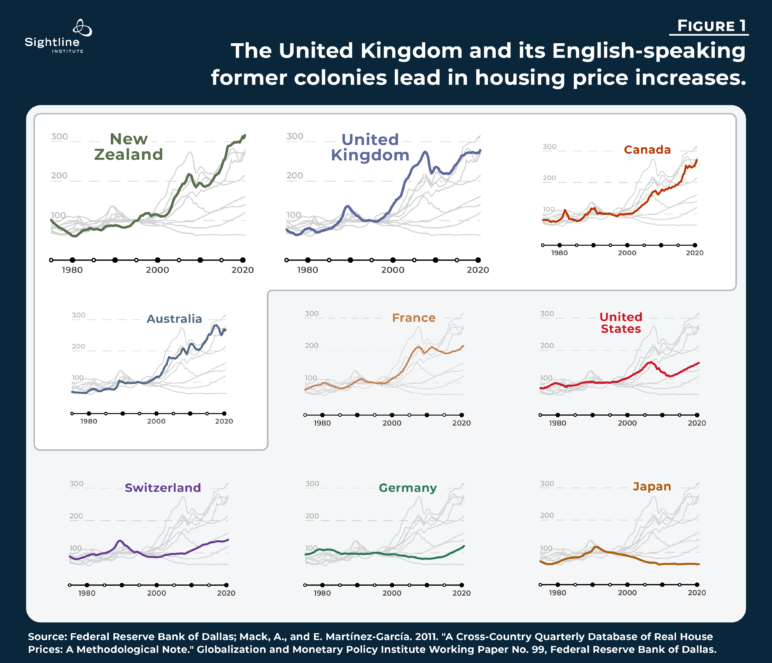

By one measure, the United Kingdom and its former colony New Zealand have the worst housing records around (see Figure 1). Like their Anglosphere peers Australia and Canada, they govern homebuilding in ways that give neighborhood obstructionists vast power, yielding tight restrictions on new homes. And they provide little incentive for local leaders to welcome more homes. Consequently—inevitably—they endure housing shortages on an epic scale, with surging and astronomical prices.

Yet recently, from these bastions of NIMBYist exclusion have sprung bracingly ambitious efforts at reform. The government of New Zealand’s progressive Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern has implemented—and the government of UK’s conservative Prime Minister Boris Johnson has proposed—efforts to disempower residential obstructionism and unleash construction of vastly more in-city housing. In Johnson’s words, “build, build, build!” Such pro-housing reforms could make these countries unexpected models for Cascadia and other tech-booming places.

The Anglosphere

When it comes to housing politics, the United Kingdom and its most Anglicized former colonies such as New Zealand are the worst in the world at providing abundant, affordable housing, according to Professor Paul Cheshire, who studies housing internationally at the London School of Economics. But they are not actually destined to fail: indeed, they have certain advantages. Like Japan and France, the UK’s largest part, England, and New Zealand have strong national governments with centralized regulatory, tax, and spending systems. They could—they have begun to—promote abundant housing through national policy. The problem is that, unlike Japan and France, they long ago delegated control over real-estate development to local governments, while, unlike Germany, giving them no incentive to welcome new homes.

In the United Kingdom, this modern supercharging of local obstructionism dates to a near-ban on development during World War II. Then, in 1947, the post-war Labour Party government of Clement Attlee enacted the Town and Country Planning Act, which led to some of the world’s strictest development controls: not only tight containment cordons around cities to stop sprawl but also limits on building heights and a system by which almost every building erected needs to win the affirmative consent of local town councils, who can deny permission for any reason or for no reason at all.

Such local, discretionary permitting did not immediately close off construction; the post-war consensus on housing was go-go. But over time, handing power to localities had exactly the same effect as it does in North America today: it gave homeowning local voters (“homevoters,” in theorist William Fischel’s term) a veto over change. By a generation later, as homeownership grew (it more than doubled to 70 percent of households in the second half of the twentieth century), localities everywhere were tightening the screws on new construction. After peaking around 1970, the number of homes built annually in the UK has fallen by more than half, even as the nation’s population has grown by more than a third.

Germany has a decentralized system of development regulation, like the United Kingdom, but it provides strong incentives to local authorities to welcome homes. German localities get money from higher levels of government based partly on how many residents they have. In the United Kingdom, localities gain no such funds. In fact, they end up paying for any new facilities needed to serve newcomers, such as schools or parks, but get scant financial help from London. The country’s revenue system pools some locally collected taxes and fees and shares these elsewhere, so even the local tax windfalls from new development tend to leak away to the chancellor of the Exchequer in London. The housing scholar Christian Hilber, also at the London School of Economics, wrote me by email:

There is an alliance of local residents who do not like local development and . . . local politicians who do not even increase their fiscal revenue when they permit development . . . . The consequence is an extremely restrictive planning system and a massive affordability crisis that has been getting worse over the last 40 years.

Since the 1970s, the United Kingdom has built about half as many new homes as Germany, despite a similar population. From the mid-seventies to the present, UK home prices have tripled, adjusted for inflation, while Germany’s have remained roughly stable, as shown in Figure 1. UK home prices are staggeringly high: in London they were, in one careful comparison, almost twice as high per square foot as prices in Paris, and more than three times as high as Tokyo’s. Rents were similarly astronomical.

Kiwi housing

New Zealand’s record is, if anything, worse. A country of five million people—just a little larger in area and population than Oregon—it is a mid-sized exporter of farm and forest products perched on the periphery of the global economy. But its housing prices are more like those one might expect in a global hub of finance or technology. The average price of a New Zealand house in late 2020 was about US$500,000, which is roughly 50 percent more than the US average.

New Zealand real-estate prices have not always been high. They only skyrocketed over the last 40 years. Since 1980, adjusted for inflation, they have grown fivefold. That’s a larger increase than in almost any of the 25 affluent countries included in the database from which Figure 1 is drawn. Since 1995, New Zealand’s prices have grown faster than those of any other country. Since 1992, home prices in New Zealand’s principal city, Auckland, have risen faster than all but one of the cities included in the Economist’s global house-price index; they have outpaced San Francisco’s notoriously escalating prices by 175 percent.

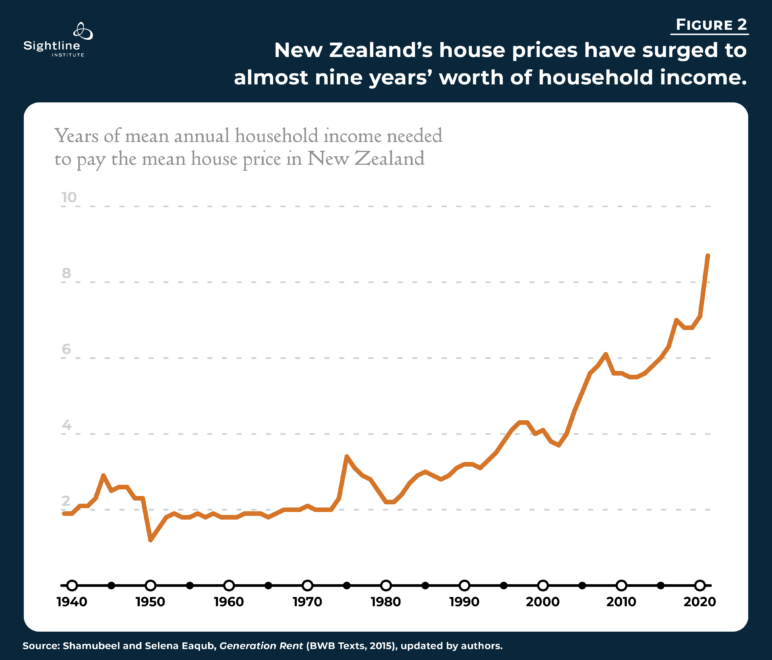

An even better measure of affordability than house prices themselves is the ratio of prices to average incomes. On this measure, New Zealand has gone from good to awful in a single generation. The Auckland-based husband-and-wife team of economists Shamubeel and Selena Eaqub assembled more than 80 years of time-series data on these ratios from official sources for their 2015 book Generation Rent. They have updated it since then and shared the data with Sightline. Figure 2 shows that from before World War II until the late 1970s, average housing prices tracked income: it cost about two years’ worth of annual earnings, on average, to buy a house. Then after the late 1970s, residential real estate climbed the walls: by 2021, it took almost nine years of income to pay for a house, a national price-to-income ratio as high as almost any in the world.

Rents have followed prices into the heights. As independent housing analyst and urbanist Brendon Harré of Christchurch, New Zealand, put it, with characteristic understatement: “Renting in New Zealand is bad.” The country’s poorest fifth of households spends almost 45 percent of their income on rent. That’s more than their counterparts in all but one of the 34 countries in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). For poor renters, in other words, New Zealand is the second worst country to inhabit in the developed world. (The worst is Chile. In third place is—who else?—the United Kingdom.) Consequently, by one measure at least, homelessness and extreme housing deprivation are more common in New Zealand than in any other OECD country—roughly four times the same metric for the United States.

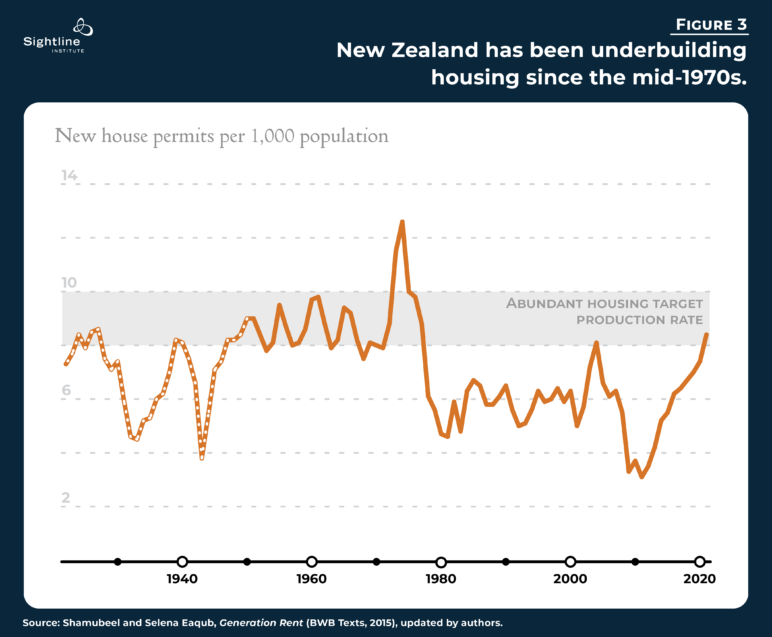

A severe housing shortage born of residential lockdown is at the root of these alarming statistics, although other factors, such as changed banking regulations and, during the pandemic, bargain-bin interest rates, have aided and abetted the spectacular inflation of real estate values. New Zealand’s Town and Country Planning Act of 1977 (later incorporated into the omnibus 1991 Resource Management Act) paved the way for local governments in most of the country to make it difficult to get permission to build apartments and houses. The Eaqubs pieced together a century of data on the number of permits localities have given to builders, including estimates for the years before 1950. Figure 3 shows that before the late 1970s, the number was almost always at or above eight new homes per year for every 1,000 residents in the country, a level at which housing shortages did not develop, and prices tracked incomes. The major exceptions, on the left end of the data series, were during the Great Depression and World War II. After the late 1970s, the number drops to a lower plateau and stays there almost every year.

New Zealand’s affluence has been rising and household size decreasing over the past century. One would expect the number of permits to increase over the century, as more people gained the means and desire to live on their own. Instead, house building has yet to match the levels that were normal half a century ago and earlier. Once homebuilding slowed in the late 1970s, prices began to rise. With each passing year of under-building, the shortage became more acute and prices rose higher. Fortunately, since 2016, building has begun a resurgence—more on that below.

New Zealand is an exceptionally centralized state, and its planning system has always been hierarchical in principle, with the national government in Wellington setting goals, regional governments drawing schematic plans, and local governments filling in the details of zoning. Still, the actual practice has put great power in local hands. Restrictive zoning, including bans on apartments in most areas, has resulted, just the same as in the United Kingdom and parts of North America.

What’s more, like the United Kingdom, New Zealand has a system of revenue that provides scant help to localities that add housing. Localities raise their funds through property taxes that are largely locked at low and steady rates by political tradition and voter sentiments. Local New Zealand governments have collected the same paltry share of economic output in taxes since the 1800s. Whereas central governments in many countries help bankroll local infrastructure, Wellington pays little. Localities are thus left with the full tab for urban services that new housing requires, from water and sewers to transit and streets. Caught between voter hostility to property taxes and the sticker shock of needed capital projects, most local leaders just stonewall: why zone for new homes at all?

Overall, local control in the absence of incentives to welcome housing has yielded residential lockdown, unusually tight markets, and massive house-price inflation. The situation is dire enough that not only home seekers and housing reformers but also mainline financial interests are alarmed, fearing a recession-inducing collapse of the real-estate market. In December, New Zealand’s largest bank, ANZ, called for intentionally deflating the housing market by building much more housing. It asserted that New Zealanders “need to be willing to accept a lack of capital gains in housing, or even be willing to stomach a fall in our asset values, while incomes catch up.”

Fortunately, in both the United Kingdom and New Zealand, elected leaders have begun to overturn the status quo, unlocking housing construction by righting the imbalance of power with local authorities.

Six floors, zero carpark quotas

In New Zealand, the action came from the left. In July 2020, Jacinda Ardern’s Labour government issued a sweeping new policy, the National Policy Statement on Urban Development (NPS-UD), which revised and strengthened planning guidance for all regional and local bodies, instructing them to ensure that land and housing markets are functioning well, which it defines as yielding stable prices and rising residential density. Defining stable prices as a national public policy goal may sound mundane, even blindingly obvious, but it’s almost never done. In Cascadia, Canadian and US policies aim, implicitly if not explicitly, for rising values.

Going further, the NPS-UD jumped ahead of town and city planners and specified that they must, by August 2022, rewrite their rules so as to:

- Eliminate requirements nationwide that buildings provide off-street parking spaces. Applying to all communities of 10,000 residents or more, this policy is the first national ban on parking quotas anywhere in the world. Quotas for parking spaces, or “carparks” in the Kiwi vernacular, dramatically increase the cost and lower the supply of housing.

- Require that planners permit at least six-story apartment buildings everywhere within walking distance of rapid transit stations and downtowns. The rule is actually written to require the permitting of enough housing to meet all demand. Moreover, it specifies that in such locations, height limits must never be less than six stories. Coupled with the goal of stable prices, this rule could push height limits to more than six stories.

Again, the scale of these changes is staggering, when compared with what North American jurisdictions have achieved so far. Californian reformers have been trying since 2018 to win a reform that would implement a similar six-story rule, and they have yet to win passage in even a single chamber of the state legislature. New Zealand’s Ministry for the Environment, which oversees planning, announced its version of the California plan in July 2020 and implemented it the following month.

The reforms did not come out of the clear blue sky. Various expert and citizen groups had been talking up similar ideas, and Auckland had completed a new regional plan in 2016 that reduced carpark quotas and upzoned parts of the city. Indeed, Auckland’s new plan partly explains the recent upswing in homebuilding shown in Figure 3. (In 2015, perhaps not coincidentally, the first city of New Zealand’s Anglosphere neighbor Australia also shifted its posture on housing: the regional government of greater Sydney assigned stepped-up housing targets to its member localities, which forced them to make zoning and other changes. Homebuilding rose dramatically.)

Still, Ardern’s Labour government was not exactly responding to a groundswell of public support. Considering the circumstances, it acted with impressive boldness. The country was in the middle of its COVID-19 winter lockdown, and the Labour Party held power only tenuously, thanks to a precarious coalition with the Greens on the left and the populist New Zealand First Party on the right. Most leaders would not challenge localities’ housing prerogatives in such a time, but Labour did it—just three months before an election. Fortuitously, Ardern’s exemplary pandemic leadership won the party a landslide in October 2020, securing itself an outright legislative majority.

Strengthened by the election, the government is now planning further reforms, including a top-to-bottom rewrite of the country’s laws on natural resource management, including land-use planning. Through this rewrite, in 2022, the abundant-housing principles of the NPS-UP may work their way into law.

Independent housing analyst Harré wrote me by email that “the changes have not caused much controversy with the public, probably due to the surreal Covid times.” Also, the parliamentary opposition, the conservative National Party, has been in disarray since losing the October 2020 election. What’s more, because the NPS-UD is mostly a deregulatory effort, it aligns with the National Party’s conservative ideology. The party has been at least half-heartedly supportive of it. As in Oregon and California, Ardern’s pro-housing reforms have won left-right backing.

October 18, 2021 UPDATE: The left-right momentum strengthened dramatically today, when the Labour and National Parties together announced a new law to legalize middle housing almost everywhere in the country. Formerly single-detached lots will now be eligible for three homes each of up to three stories. It’s a big move toward housing abundance and lower home prices and rents.

By-right development, two extra floors

In August 2020, the month that New Zealand’s Labour government implemented the NPS-UD, the United Kingdom’s Conservative government announced a proposal of even greater boldness for the most populous jurisdiction of the United Kingdom, England. This “biggest shakeup of the planning system in decades,” in the words of Foreign Affairs, would speed and streamline homebuilding by stripping localities of discretionary authority over many building projects.

Introducing the proposal, Prime Minister Boris Johnson wrote, “Thanks to our planning system, we have nowhere near enough homes in the right places.” “It’s time,” he said about the planning system, to “tear it down and start again.” Calling for “radical reform unlike anything we’ve seen since the Second World War,” he termed the proposal “a whole new planning system for England. One that is clearer, simpler and quicker.”

The proposal calls for local zoning authorities to divide all land into three categories: one for conservation, where few building permits would be issued; one for “renewal,” where infill development would be allowed when it conforms with local rules for middle housing and “gentle density”; and one for growth, where building permits would be much easier to get and localities would have less power to intervene. Discretionary permitting would give way to by-right permitting, as on the European continent: if your project checks the boxes, authorities must OK it. Local councils would stop spending their time judging building proposals one by one. Instead, they would write clear, simple, and prescriptive rules. Developers could then design structures that obeyed the rules and be assured of winning permits.

Less noted by the news media, the proposal also includes experiments with hyperlocalism—the innovative plan developed by London YIMBY’s John Myers and allies that I described earlier in this series. Under hyperlocalism, residents of individual city blocks gain authority to upzone their own block by supermajority vote under certain conditions. Conceived as a way to flip the valence of homeowners’ self-interest, giving them a big enough stake in well-designed infill development to overcome their customary aversion to change, hyperlocalism holds great theoretical potential. It needs a chance to get started and perfected in the real world. If it does, widespread replication might follow.

Given the wide range of zoning rules allowed, though, obstructionist localities could quash homebuilding simply by writing intentionally onerous rules. That’s what has happened in Cascadia, which has something closer to by-right permitting than most of North America. To safeguard against such subversion of its purpose, the Johnson government added teeth to its proposal: the central government would assign ambitious targets for new homes in each locality. If a locality didn’t hit its numbers, London would step in.

The Johnson proposal is stunningly bold. If those targets were implemented, it would bring a big improvement in English housing undersupply. But so far, it’s only a white paper, not a policy. The Tories did make two noteworthy reforms promptly and outvoted Labour opponents in Parliament to make the changes stick: one allows two extra stories subject to discretionary approval in some residential zones, and the other allows more conversions of vacant commercial buildings to residential uses. Both reforms have limits, but they mark an auspicious start.

The key questions, of course, are when the government will introduce a bill in Parliament to create its new planning system and what exactly it will include. Since the end of a three-month public-comment period in October 2020, the government has said little. What it has said has mostly been backpedaling. Eleven months after Prime Minister Johnson said of the planning system that he would “tear it down and start again,” Housing Minister Robert Jenrick said, “I don’t think we need to rip up the planning system and start again.” He also announced a delay in action on the proposal, until late this year or next, and a slew of other steps that weakened the 2020 proposal. The (London) Times reported on September 11, 2021, without citing its sources, that the proposal, once finalized and released, will substitute designated “growth sites” for a wholesale rezone and will include housing targets that are not mandatory.

The cause of this delay and retreat is undoubtedly political. The proposal kicked up a hornet’s nest of concerns, not only from Labour and its allies but from Tory members of Parliament. As many as 100 Conservative MPs may oppose the plan, which would be more members than even Johnson can spare to lose. His smashing December 2019 landslide victory gave him the biggest Conservative majority since the 1980s, but his margin was still only 84 members. In June 2021, it dropped to 83: the centrist Liberal Democrats shellacked the Conservatives in a special election in a suburban seat the Tories had held since 1974. Some observers blamed the housing plan.

Still, it’s too soon to write an obituary for Johnson’s ambitions. He has not shied from controversy in the past, including courting intra-party conflict and even purging dissident MPs. Cross-party support is conceivable, as seen in New Zealand and Cascadia. And even a watered-down version of his proposal might still be one of the most dramatic moves against residential lockdown in recent history. The initial scope of his plan is so large that even a quarter of a loaf would be a lot of bread.

What’s more, says John Myers of London YIMBY, “even in in the absence of other proposals, implementing hyperlocalism could be a game changer, both for England and for other places like it.” A parliamentary bill for a strong form of hyperlocalism has gained momentum, with endorsements from an impressively diverse array of interests, including both opponents and supporters of Johnson’s broader plan. On September 14, the Daily Telegraph reported, the government embraced the bill and indicated it would incorporate its tenets into its still-pending planning bill.

Lessons for Cascadia

The differences between New Zealand and England’s successes to date are mostly a function of the institutional and legal structures in which they operate. New Zealand’s Ministry for the Environment has authority to guide local land use policy, while in England, Parliament holds that power. New Zealand’s reforms, therefore, are well under way, while most of England’s have yet to move from policy whitepaper to draft legislation. In time, Parliament will act on Johnson’s proposal, and we will see what comes of it.

But even before the denouement in England, Cascadia and its housing-scarce peer regions in North America can draw two lessons from Ardern and Johnson’s actions.

First, bold and decisive leadership from above is indispensable. Local housing shortages are a tragedy of the commons: each elected official in a small, local jurisdiction within a large, modern metropolis gains little and risks much by allowing more housing. Only action coordinated from a higher level can yield large rewards and small risks.

Second, housing abundance is an agenda owned by neither left nor right. Indeed, if deployed adroitly, it is a political opportunity for either. Prime Ministers Boris Johnson and Jacinda Ardern are tribunes of the two great opposing traditions of Anglosphere politics: Conservative and Labour. They have spent decades arguing with each other’s political philosophies and running campaigns against each other’s co-partisans (although in different countries, of course). Both won historic electoral landslides in the last two years, demonstrating their immense gifts as leaders—their abilities to identify and activate public sentiment in favor of their party.

And both seized, perhaps surprisingly, on abundant housing through national land-use planning reforms as policy initiatives worth attempting. Both did so by asserting an overriding public interest in abundant housing. And both sought to advance that interest by righting an imbalance between local and national control over homebuilding.

The countries with dominion in Cascadia—Canada and the United States—are federated countries, not unitary ones like England and New Zealand, and control of land use is in the hands of subnational governments. Where land use policies are concerned, the analogous figures to Johnson and Ardern are therefore not the US president and the Canadian prime minister. Rather, they are the governors of the states and especially, the premiers of the provinces. These executives have the political positions, and—in the case of the Canadian premiers who lead parliamentary governments like those in the rest of the Anglosphere—the legislative powers to emulate the UK and New Zealand.

The question, therefore, is which Cascadian governor or premier will first emulate Jacinda Ardern or Boris Johnson—leaders whose countries are among the worst places in the world for affordable, low-carbon, urban housing but whose actions, one from the left and one from the right, aim to swiftly transform their countries from epicenters of residential lockdown to showplaces of abundant housing.

Will it be a governor from the left, such as Oregon’s Kate Brown, who has already signed a first-in-the-nation statewide middle-housing law, or Washington’s Jay Inslee? Will it be a governor from the right, such as Alaska’s Mike Dunleavy, Idaho’s Brad Little, or Montana’s Greg Gianforte? Or will it be British Columbia’s labor-aligned New Democratic premier John Horgan, who leads a province with striking similarities to New Zealand both in government structure and in housing shortage, and whose party, like Ardern’s, leaped during the pandemic from a tenuous coalition government to an outright majority?

And whoever does it first, will they be able to mobilize enough legislative votes to tear down exclusionary old rules and “build, build, build” abundant housing in compact, low-carbon communities?