When thousands of people are living in tents and doorways, it makes no sense for the government to stop people from living indoors.

But that’s exactly what some cities and counties do by capping the number of “unrelated occupants” who can legally share a home, no matter how large. Both Oregon and Washington are considering state laws that would strike down these outdated rules.

The Oregon bill, HB 2583, is set for its first hearing in the Housing Committee of the state House of Representatives. It’s sponsored by the committee’s chair, Democratic Rep. Julie Fahey of Eugene. The bill could hardly be easier to summarize. Here’s its latest draft, in full:

“A maximum occupancy limit may not be established or enforced by any local government, as defined in ORS 197.015, for any residential dwelling unit, as defined in ORS 90.100, unless the restriction is based on the square footage of the entire unit.”

In Washington, the equivalent provision is part of a larger bill, SB 5235, that would also strike down discrimination against tenants on lots with accessory dwellings. (Oregon already passed such a rule in its 2019 legalization of middle housing.) That bill, from Democratic Sen. Marko Liias of Mukilteo and others, passed out of Washington’s Senate Housing and Local Government Committee last week.

My colleagues Nisma Gabobe, Dan Bertolet and Alan Durning have all walked through the reasons these bills are good. Last year, Nisma surveyed 228 cities across Washington and found that 71 percent had these exclusionary clauses in their zoning codes. All of them are, essentially, government attempts to define who is and isn’t a “family.”

That’s simply not appropriate in 2021. And various states are agreeing. Iowa passed a law striking down unrelated occupancy limits in 2017; state courts in California, Michigan, New Jersey and New York have done the same. Oregon’s largest city, too, is poised to remove its own cap on unrelated occupants in a matter of weeks.

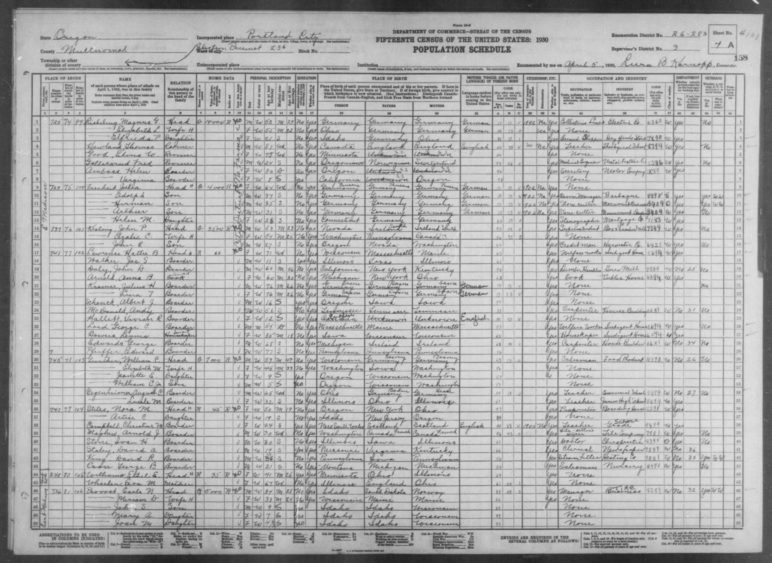

a housing innovation, learned from the past?

A data sheet from the 1930 US Census, on Madison Street in inner Southeast Portland. Out of 50 residents listed at eight addresses, 22 were identified as a “boarder” or “roomer.” Image via Gerson Robboy.

One of the people who read Alan’s work on this subject years ago was Portland housing advocate Leon Porter. He was inspired by the possibility of opening up the glut of empty bedrooms hiding in plain sight.

Porter has even dug deep into current Census figures to put a number on that glut: Across Oregon, there are at least 1.5 million bedrooms that no one is sleeping in. That’s in both occupied and vacant homes.

In 2019, Porter began talking to people about an interesting concept. First, re-legalize shared homes by ending caps on unrelated occupants, with size-based exceptions for fire safety and overcrowding. Then, use potentially small subsidies to help voluntarily turn at least a few of these empty bedrooms into homes for people who don’t currently have any.

Porter draws inspiration from past housing shortages. Once, he says, it was perfectly ordinary to rent out spare rooms.

“I think that culturally, people no longer think as much about setting up rooming houses or boarding houses as an obvious way to make use of extra space in their homes as they did 100 years ago,” Porter said in a 2020 interview.

“Removing that regulatory barrier is an essential step to having this becoming a widespread solution,” he explained. “I don’t think that just changing the group living rules by itself will have a huge impact. Because a lot of people probably do it now, just illegally. But if we’re going to have nonprofits—or governments themselves, potentially—setting up group living or home-sharing situations, they’re not going to be able to do it easily if it’s just a conditional use.”

Once home-sharing is no longer technically illegal, Porter said, cities and nonprofits might be able to partner to open up relatively low-cost housing for some people experiencing homelessness.

“It might not take very much money at all to tap into these bedrooms,” Porter said. “It might simply be a matter of paying for a screening process or maybe subsidizing the rents of these bedrooms a little bit. … What we can do is facilitate programs with people who are living in these really big houses who are lonely and are having trouble paying the mortgage and would like some roommates who have been pre-screened and are safe to live with.”

“A close friend of mine is a 60-year-old woman who’s homeless,” Porter added. “I know from first-hand experience that she’d be a great roommate. But it needs to be facilitated to make it happen.”

No one expects a huge share of Oregon’s 1.5 million underused bedrooms to be rented out, whatever the scenario. But even a tiny share of them could go a long way for not much money. And Oregon may soon be looking for creative ideas like Porter’s. House Bill 2003, passed by Oregon legislators in 2019, requires cities and counties to develop concrete strategies for housing many more people and bringing many more homes into the market at low costs.

If just one in 100 of the underused bedrooms in Oregon could become long-term housing, that’d be enough to house 15,000 people. According to the United States Department of Housing and Urban Development, that happens to be the approximate number of Oregonians without homes as of January 2019.

Nisma Gabobe contributed to this report. An earlier version misstated one of the effects of SB 5235 on ADUs in Washington. The error was mine.

Liz Getty

This is surely a stretch, but somehow this law has always reminded me of my Ohio college campus’ rules on having more than 10 woman in one house being considered a brothel. Law should adapt as the world around and use change; especially now considering our online existence for over a year (isn’t a habit established in 3 months;). I keep thinking about all the newly abandoned vertical, sprinkled and retrofitted space across the country for the ever desired live work space.

Sabra Marcroft

This is an important foundational step for allowing more types of shared housing such as co-living to happen in existing neighborhoods. Thank you.

Megan Basl-Huff

This is an amazing thing an people have become so cruel to other and no longer care. It should also be okay for people to park on property of family etc that have the extra space and own there property unless landlord don’t approve of it. There is no reason that american have the be so selfish it’s been this way for years. Please approve this and help the housing crisis and I’m sure it will improve. Everyone needs help right now but most won’t admit it. Just because some one is homeless doesn’t make them bad people. We experienced a house fire and then ended up not being able to find a place to rent due to rules being so strict and everything is out ragisly expensive. I don’t know how landlords and mortgage compamys can get away with that either. They are helping make the American people suffer no matter where it is. Some of the best people are people without money etc. Money is the evil part. You also have familys that require children to have separate rooms due to not being able to get along or maturity levels etc and that need to be worked out through housing also. I’m great ful I have family for myself and children. We have been waiting for housing and still nothing due to it being so far back up that’s the next issue needing asst. I hope that higher up people will see the light and start thinking instead of not thinking just because they have money they have the funding they need who cares about others. Please take care of the landlord pricing next, there should be a limit but 2 bedrooms go for over 1000.00 that’s crazyness. Something has to give it’s not right no one can get ahead or get on there feet unless there upper class and then u have the credit scores that landlords are using that’s wrong also very very wrong. That should only be if your buying etc a credit score doesn’t make a person.

Todd Boyle

Honestly I don’t think removing the cap will result in more bedrooms in Eugene, we already allow 5 people and there aren’t that many really large houses here. Those that exist, the rent’s too high.

The State needs more units below $300/month. Oregon has 100s of thousands of people living on less than $1000/month. Policy makers need the humility to admit the fact there’s no housing for the extremely low income (ELI) and either build 100,000 units of low income housing, or allow the poor to house themselves by whatever means they have: RVs, Tiny Houses, conversions of garages and sheds, and yes, tents.

The problem of homelessness and extreme rent burdens over 50% of income is directly traceable to zoning and building code restriction. HB2001 allows 2,3, and 4 plexes, cottage clusters, etc. In a rational world, you would quickly see multiple Tiny Houses being built in yards of older, cheaper homes. I live in one– an absolutely lovely converted garage without plumbing; I share the facilities in the main house. But the City wouldn’t allow a bathroom and kitchen in my converted unit. That’s the sort of thing HB2001 is supposed to change but my City Council member is dedicated to preserving the status quo in his district. So it will be many years before HB2001 is implemented to actually allow more housing at the cost level affordable by the bottom 10%.

You need a pipeline of new housing units constructed below $50,000. Current prices per unit of new construction of course is more like $300,000 per unit in both the private sector and public housing. The State can reach $50,000 by the cheapest manufactured units on government owned land. Since we know that’s not going to happen, policymakers should admit the facts and allow the poor to house *themselves.* Because what the State and its municipalities are doing is basically telling the poor, tough luck buddy, and no, you can’t live in a Tiny.

Ned

This story strikes me as a provocative distraction. How many people are being arrested for breaking this law? 1.5 million unused bedrooms-I would like to see the peer reviewed documents on that. Let’s focus real time and money on erasing Homelessness.

Michael Andersen

Almost nobody’s being arrested, if any. As noted in the second section of the story, the main effect of legalizing this would be to let businesses, nonprofits and governments build scalable homelessness solutions around it.

Tim DuBois

Michaels response is the main reply to your post though I want to add. I was a residential carpenter for 9 years and my experience suggests this number is completely reasonable but the exact number is not critical for the larger argument brought by Michael and Leon. In addition this policy does not require any significant amount of time by our lawmakers, certainly no time that distracts from direct homeless solutions plus it is a cost free policy change. So there is no distraction here. It is simply a policy that would reduce the minimum housing standard that in its current form is higher than many people can afford, pushing them onto the streets.

Alec

I’m still confused if the WA bill would practically do anything in regards to occupancy limits. This is what I’m reading from the WA bill noted in 3 sections at the end:

“…Except for occupant limits on group living arrangements regulated under state law…” This “state law” isn’t specified here.

From the bill reports:

“Except for…limitations based on occupant load per square foot and generally applicable health and safety regulations established in an ordinance or applicable building code…”

“Allows generally applicable health and safety provisions in applicable building codes or county ordinances to regulate or limit the number of unrelated persons that may occupy a housing or dwelling unit.”

So a city or county could just make a “parking space per capita” law if this bill passes and that would be adequate to effectively reinstate occupancy limits of unrelated people? What’s defined as a “health and safety provision”? If it’s “generally applicable” is it often inappropriate? Looks like they’ll just change other laws in the books to make things worse.

This legislation also looks like it would let cities require parking for ADU’s regardless if the tenant needs it or not.

Ray

6 problems I have identified that have to be overturned and changed.

1) There need to be restrictions on Banks and property companies that jack up costs well beyond the actual worth of those locations to rent or buy. In short we need a price cap to compensate for the “Housing Bubble” caused by all those pooled bond properties and artificially jacked up pricing back in 2008 which we have still been feeling the consequences of (the latest ponzi being Crypto but that is something else and far worse).

2) If you own a property you should be allowed to rent out any bedroom in the house you own regardless if related or not the same way a property company can rent out a crappy studio apartment often times no bigger than a motel room and significantly higher in cost than said housing actually costs. It is no ones business what their “personal relationships” are with one another and what they choose freely as consenting adults to do in those bedrooms and its not the “State’s job” or authority to play Morality Police.

3) Allow people to buy abandoned properties who are on such as fixed or limited incomes first regardless of their credit history and limit it. For example if the property is appraised at $50,000 for say a manufactured 2-3 bedroom home, then said fixed incomes or low income individuals first to be granted opportunity to rent or buy, should not be made to put down more than 3%, not subject to a credit check and that would allow them to put $1,500 down which for two working people as a couple or just roommates means they jointly come up with $750, and with a no more than 5% interest rate that translates to around about $370-$400 month total towards ownership having covered the basic property tax which is on average about $150 a lot per actual appraised real and not artificial values.

4) They also need to Open up the HUD Grants for said individuals for any needed renovations or additions such as wheel chair access, repairs, maintenance and general cosmetics like a paint job, and that said grant covers having a licensed electrician to come in and update the wiring and allow said buyers to install fully owned free and clear Solar Panels to help reduce overall energy costs without that effecting the price or value of the home. And when needed proper recycling of such things which would also help our power grid significantly will also help in options for reducing E-waste (electric based products).

5) The only “background check” that should be allowed is such as criminal history pertaining to person to person crimes and vandalism to insure said first time owners are not actual problem elements that simply terrorize neighborhoods “because they can” regardless of the latest politically used excuses.

6) Don’t play the “welfare game” with this housing plan where people are given first access based on anything such as gender,sexual orientation, ethnicity or whether they have small children or not. It should only be based on their financial factors and nothing else.