First, the good news: Portland is finally proposing to stop regulating, in its zoning code, who does and doesn’t count as a “family.”

Ending these de facto limits on housemates, still common in many cities in the Pacific Northwest and elsewhere, is something we at Sightline have been urging for years. Housemate caps commit the simplest sin there is against both environmental sustainability and housing affordability—they make it harder to voluntarily share living space and stuff.

There’s no good reason to discriminate in this way against non-“nuclear-family” households. It’s great that Portland is acknowledging this.

Next, the bad news: The city is considering replacing this foolish old rule with a foolish new rule.

This one would instead restrict the number of “bedrooms” a new single-detached home is allowed to have before it becomes categorized as “group living.” The newly proposed six-bedroom cap would apply even to low-density areas that already have tight limits on building size, shape and height.

The proposed switch is part of a sheaf of reforms intended to legalize more low-cost options for where to live, from emergency shelters to tiny-house villages to small homes on wheels to group homes. Portland officials call it the “Shelter to Housing Continuum Project.” After the planning commission weighs in over the next few weeks, it’ll head quickly to city council.

“This is likely to become law as early as this spring, so it’s on a very fast track,” Portland-based ADU consultant and housing advocate Kol Peterson said in an email.

The law shouldn’t punish people for forming households beyond their ‘family’

Marketing photo for The Grove, an Open Door co-housing community. Rents for the project just off Northeast 42nd Avenue start at $680.

Local housing advocates are generally enthusiastic about the project’s changes. But the proposed bedroom cap is one part that’s raising eyebrows.

“There are very legitimate reasons for people to have six bedrooms,” said Dani Zeghbib. “What if you have two parents who work from home and they have four kids and they’re in Zoom meetings all day?”

After all, the city’s official definition of “bedroom”—at least 70 square feet and a window—applies to rooms many households might use as a home office.

That’s a point that takes on new importance in a country where telecommuting may be indefinitely skyrocketing. It’s a trend the city says it is eager to embrace for environmental and fiscal reasons.

A needless bedroom cap is also an obstacle to the single most common way to save on housing: living with roommates.

“Kitchens and bathrooms are obviously the most expensive part,” said Zeghbib, a resident of Portland’s Lents neighborhood who owns and rents out two duplexes and who has been considering adding a new co-housing structure to the relatively large lot she lives on. “If six people can share a kitchen, that means that your housing is less expensive for each of those six people. But if eight people can share a kitchen, then that’s even more affordable.”

Zeghbib and Eric Lindsay, a local real estate asset manager, independently mentioned two recent co-housing projects in Portland, The Village by Owen Gabbert and Flora & Ulysses by Orange Splot, that used one-unit buildings to create small-scale, low-cost co-housing options in low-density areas.

Both properties are now managed by Open Door, a company that specializes in helping mostly-single tenants build interdependent communities with private bedrooms but shared, heavily used common spaces. Their bedrooms rent for 30 percent less than a comparable studio apartment—as little as $680 for the smallest bedrooms in the newly built Flora & Ulysses just off NE 42nd Avenue.

Lindsay hopes to create something like that on his company’s land, too.

“We have plans on the books for two side by side six-bedroom houses that we would rent as co-housing,” he said. “When we were doing our pro forma, the ability for it to work at six bedrooms looked much more likely than the ability to make it work at five. … For every extra bedroom you slice off, you’re going to get fewer projects.”

And what, exactly, is the problem with letting the residents of an eight-bedroom home save money by sharing a kitchen if they want to?

Especially if existing fire codes already regulate occupant counts and the size and height of the building itself are already tightly regulated?

This zoning code proposal was based on an ‘arbitrary’ building code practice

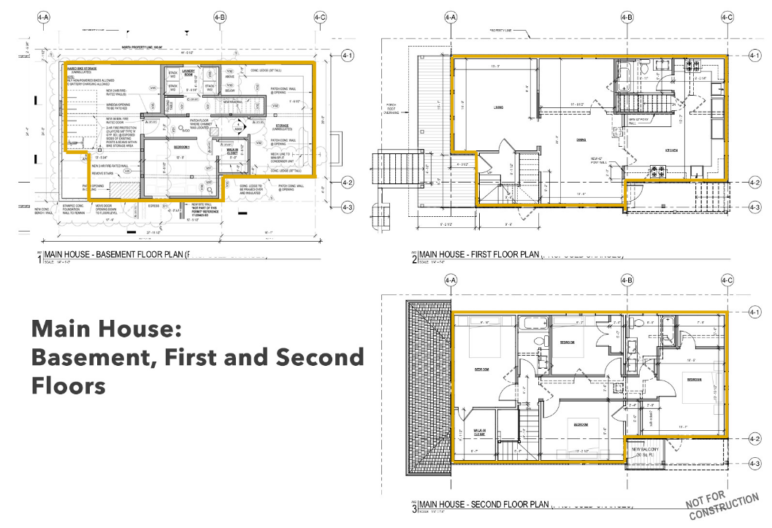

Floor plan for The Village, an Open Door co-housing community in Portland with a shared kitchen and private bathrooms. Rents for the community on N. Michigan Avenue start at $850.

Terry Whitehill, who oversees enforcement of Portland’s building code, said in a December interview that it was co-housing projects like those that inspired a new practice from his office, early in 2020.

Starting this year, his code officers have been told to consider any one-unit building with more than six bedrooms to be “congregate living” and therefore subject to parts of the more expensive and complicated commercial building code.

Whitehill described that as essentially “an arbitrary decision in-house.” He did make some effort to root it in the text of the international building code with which all Oregon cities must comply—but the language he points to for that rationale is itself due to be removed from the building code in a few months.

It’s worth noting at this point that this six-bedroom cap Whitehill and his colleagues read into the building code is different from the six-bedroom cap that the Planning and Sustainability Commission is considering adding to the zoning code. The building code, not the zoning code, determines which projects qualify for less expensive residential building codes.

And it’s legitimate to treat co-housing projects somewhat differently when it comes to fire safety. Whitehill’s job is, ultimately, to read between the lines of ambiguous building codes. He’s within his authority and his expertise to do so.

The issue, though, is that Whitehill’s building-code policy is a legally nonbinding administrative decision. A new cap on bedroom count in the zoning code would carry the force of law, and could eventually be used to justify other laws.

When asked to justify the proposed new six-bedroom cap on “household living,” city officials point only to the admittedly arbitrary decision about building code enforcement.

“We thought it would be convenient to line up with what the building code people were practicing,” said Eric Engstrom, a principal city planner who oversees the project.

Engstrom said that “from a big picture standpoint … it would be good to eventually reach” a zoning code that doesn’t attempt to differentiate at all between “group living” and “household living.” But the city has been racing to complete this reform by April in order to coincide with the anticipated end of the homelessness “emergency” Portland declared in 2015. Engstrom said a cleanup of all references to “group living” would have taken too much time to work through by then.

A short-term tweak: At least raise the cap to eight ‘bedrooms’

What is a household? It shouldn’t be a matter of zoning. Image: Evil Erin, used with permission.

This is just a small part of a fairly large and important project. But here is a simple counterproposal: in low-density residential areas, the city could set the zoning code’s cap for “group living” at eight “bedrooms” rather than six.

Why only in low-density zones? Because there are legitimate reasons to regulate large multi-household structures with commercial buildings, fire codes and so on. Starting in 2021, Portland’s low-density zones will have newly tight building size caps that prevent projects from going too far over this line. A too-low bedroom cap adds further restrictions for no clear reason.

Why eight bedrooms? As Engstrom said, in the long term the city should probably try to remove this line completely and base its zoning code on a building’s size, not its use. But there’s no telling how long it might take the city to get to that, if ever. And until then, it’s better to draw a line that punishes fewer projects—especially low-cost shared-housing projects—for adding an extra bedroom or a shared office. Especially if the result is no larger than any other one-unit structure.

Portland’s Shelter to Housing project is, many housing advocates agree, a significant step in the right direction. No local code reform project in years has more directly affected the lives of the thousands of Portlanders struggling to stay housed.

There’s no good reason to mar that record with a new, essentially arbitrary limit on the options of people who want to share their living space.

Chris

My single-family house, occupied by four people, appears to have nine “bedrooms”, if I am reading the code correctly, maybe even ten. This is in a two-story 1920s Craftsman that is less than 2000 square feet.

The rooms’ use during this pandemic shows that you don’t need a family of six or eight to show the silliness of this proposed rule. We have three real bedrooms, four spaces that are used individually as home offices or school classrooms, and two family living spaces. Our situation is not unusual among local families with two or three children.

Joe King

The average US home is now 1,000 square feet larger than 50 years ago. Meanwhile, the average household has decreased by about a full person in the same time period. Doesn’t make sense to overbuild homes for the households that will inhabit them. I don’t want overbuilt, underpriced homes in my neighborhood bringing my property value down.

Michael Andersen

That’s entirely true about home and family size trends, and it’s why Sightline, among others, fought so hard to allow smallplex options and lot divisions in Portland’s recent reform to low-density zones. Without those changes, home sizes would only keep heading up and up and up. Building smaller homes in most of Portland’s low-density zones has been economically infeasible; that will now change.

But that’s not the issue here, because building sizes in low-density zones have already been capped by the residential infill project. What the city is proposing here is to *also* begin micromanaging how people use their newly limited amounts of space.

More generally, I don’t think we should go from putting a thumb on the scale to favor overconsumption of housing (as we were when we banned smallplexes from most of Portland) to putting a thumb on the scale to favor underconsumption of housing, especially in a relatively transit-rich, job-rich city like Portland. Some households ARE large, and we want large households to be able to choose to live here, if they prefer, rather than in Battle Ground. We’ve already made that a little harder by capping building sizes. Do we want to start making it harder still by regulating bedroom count?

Robin Quinn

Businesses in shambles or permanently closed down after 100+ days of violence, looting, and burning in downtown Portland, rampant homelessness, drug addicts shuffling around everywhere, tax paying productive people fleeing the city for places that actually enforce law & order (red states), and Portland is focusing on how many bedrooms someone can have in their home. Sums up perfectly why Portland is in the mess it’s in now.

“This bedroom has an oven in it” ~ Mitch Hedberg

Eli Spevak

I agree with almost everything in this article. But outside of the building code interpretation (which I agree is a hurdle), I don’t see where the ‘punishment’ is coming from for going beyond 6 bedrooms. It might seem like there’s a punishment. But by allowing group living by right (up to 3,500sf), it’s just a matter of labeling. Note that the coliving communities sited in this article would all fall well within this cap.

I agree that what should really happen is a merger of household and group living into a single category with this code update. But making them both by-right is a pretty solid bridge measure, I think. More problematic is the building code interpretation change (which was done with zero public process). Maybe that could bump to 8 BRs as the threshold…

Michael Andersen

It’s correct that the city’s current proposal is to allow group living by right. That’s great! If only more cities did this.

But even in Portland, there is no guarantee that this will be the case forever. It’s not hard for me to imagine a few high-profile projects leading to a backlash against the “group living” designation in a few years, and that leading to the re-positioning of group living as a conditional use. (As you know, this is why parking requirements near transit were muscled back into the code a few years ago, just a few years after having been removed, and it required the legalization and creation of an inclusionary housing program to muscle them back out, at least for now.)

There’s also the question of validating the arbitrary building code interpretation. It seems to me that it’ll be a lot harder to change that if it’s being validated by the local zoning code. Not that an eight-bedroom cap in the zoning code wouldn’t be equally arbitrary! It’s only that fewer buildings would trip over it.

HANK

As a designer working within Portland’s already challenging zoning system, I’m dismayed with the new rules set to come into effect next fall. Nothing I have to say about these new rules is anywhere as kind and generous as the what the folks have written above. Regardless of the lunacy of telling people how many rooms go into a single family home, you aren’t going to be able to build one big enough to put that many rooms into.

Michael Andersen

I don’t love the new caps on building size either, though I think they were a necessary compromise required to legalize up to fourplexes. But I don’t think it’s actually *that* hard to find lots where more than six bedrooms (or “bedrooms”) would be easy to fit into a one-unit home if someone wanted to:

– On a generic 7000 sqft lot in R7, you get 2800 sqft of building

– On a 5000 sqft lot in R2.5 (the row of such lots I recently lived across the street from, for example) you get up to 3500 sqft

– On a 9700 sqft double lot in R5 (the one I recently lived next door to, for example) you have the potential for up to 4850 sqft and, under these proposed rules, get the first 3500 sqft by right

– If you are able to excavate, daylight-basement space doesn’t count against the new square footage limit but would count toward the bedroom cap