Last time, I asked what political strategies can circumvent the trench warfare of local upzoning and unleash abundant home building in low-carbon neighborhoods. In this article, I lay out the scale of the housing challenge in more detail.

To grasp the daunting scale of the challenge of abundant housing in low-carbon cities, we could start various places, but let’s start with the clock. Because it is running out.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) says we have until 2030 to turn climate-disrupting emissions steeply downward.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) says we have until 2030 to turn climate-disrupting emissions steeply downward. Adding more homes to neighborhoods that are compact and have a rich mixture of dwellings, shops, and workplaces is an essential step to a beyond-carbon economy. Done right, urban living allows people to share walls, shed cars, and shorten trips, which causes energy demand to plummet. As more people share space, greenhouse gases disappear: each doubling of density slashes emissions per household by almost half from transportation and by more than a third from home energy use.

What’s more, housing built in existing neighborhoods is an engine of economic opportunity for the less-advantaged, and it’s an indispensable component of any solution to the housing shortages that grip many prosperous cities. Building homes on the exurban fringe is relatively inexpensive for the builders, but for the families who live there, the added transportation cost in cars, fuel, and time can erase the savings on rent or mortgages.

We in Cascadia, like our counterparts in other expensive, tech-booming regions, are already decades behind on building apartments, duplexes, and other housing in compact neighborhoods. Just in the years from 2000 to 2015, Washington fell 226,000 homes behind in the race to keep its dwelling numbers up with its population. In Oregon, the gap was 155,000. Those chasms—equal to 7.5 percent of all homes in Washington and 9 percent in Oregon—largely explain the surging rise of home prices and rents. In California, the poster child of housing shortages, a separate analysis says the state is missing 3.5 million homes. (By “home,” here and throughout this series, I mean a single dwelling unit, whether it is in a rooming house, a tiny house, a cottage, a rowhouse, an apartment or condominium building, a mansion, or some other structure. A home is a place to be, with cooking, bathing, living and sleeping facilities, and a door to close. It is, in the words of Maya Angelou, “the safe place where we can go as we are and not be questioned.”)

The systemic, decades-long slowdown in homebuilding in Cascadia and other centers of the new economy have closed off and reversed the historic pattern of economic development in the United States, in which each era’s super-productive cities—New York, then Chicago, then Detroit, and so on—become magnets of population growth. Such city-led surges in innovation and productivity have dramatically raised prosperity in the United States overall, as Edward Glaeser documented in Triumph of the City. These growth centers have also served as principal engines of upward mobility for low-income families, not only those who already lived there but also those who migrated from around the country and the world to find jobs that lifted them into the middle class. Not just the traumatic migrations, like Okies fleeing the Dust Bowl for opportunity in the West or the Great Migration bringing 6 million African-Americans from the South to the industrial North, but also and more importantly the much larger phenomenon over decades of Americans relocating to take better jobs has been a wellspring of upward mobility.

In contrast, in recent decades, tight building restrictions in the nation’s current generation of innovation centers—places like Silicon Valley and Puget Sound—have elevated housing costs so high that they have reversed the normal migration patterns. Low-skill and low-income workers are moving to low-productivity cities in the Sun Belt, not for high-paying jobs (wages there tend to be low) but for their abundant, if sprawling and auto-dependent, housing. The costs of this inversion are titanic, for national prosperity, economic opportunity, and climate stability. Exclusionary land-use policies in mostly blue coastal cities are the root of the problem. “The inability of millions of Americans to move to where opportunity is puts a huge brake on economic growth, and constrains the historic engine of economic mobility,” write conservative economist Brink Lindsey and liberal political scientist Steven Teles in The Captured Economy, their recent summary of research into the cumulative effects of local zoning.

In short, we in Cascadia are failing to welcome the compatriots who, by historical precedent, ought to be arriving by the hundreds of thousands to staff the digital revolution—the revolution Cascadia’s tech firms are uploading to the planet.

Train arriving by brewbooks used under CC BY-SA 2.0

Moreover, we Cascadians are unprepared for our role as a climate refuge for our continent and beyond. Already, the metropolitan strip from Eugene to Vancouver, BC, is home to 10 million people, and by the time this year’s newborns turn 30 and have children of their own, that number will have jumped another 3.5 million, according to the region’s planning agencies. But even that number is likely an underestimate. The projections it’s based on do not reflect the climate chaos that’s already striking with disturbing frequency and that is making Cascadia seem like a haven. The region has no plans that will accommodate the millions of people likely to arrive in the years ahead if, as expected, climate disruption hits other places even harder than it hits us. If climate models are right and Phoenix’s climate becomes like Baghdad’s, while Los Angeles’s becomes like Phoenix’s, we Cascadians had better start thinking about where we are going to put everyone. They will come—do not doubt it. They will come drawn to our temperate weather, plentiful water, and the promise that our regional economy, agriculture, and health will suffer less than others’. If we don’t find places for these people—if we don’t allow construction of an abundance of housing for them in urban neighborhoods—the richest of them will price out the poorest of us. The housing market is, after all, like a cruel game of musical chairs: unless there are enough homes for everyone, people without money always lose.

Many Cascadians recoil at the prospect of so much change, of, for example, a doubling of population in Cascadia within a generation and growth of Cascadia’s Portland-to-Vancouver, BC, spine from 10 million to 20 million, rivaling present-day New York City for metro-area population. “Can’t the growth go somewhere else?” floats between the lines in community meetings. I am a Seattle-born child of the 1960s and get misty-eyed rereading E.F. Schumacher’s Small is Beautiful, so I relate to the sentiment. But it’s a vain hope. Worse, it’s a dangerous distraction. There’s absolutely no use complaining, and no time to squander on wistfulness. Under the US constitution and Canadian law, states and provinces—to say nothing of localities—aren’t allowed to throw up walls at their borders and choose who gets in. What we can do is upgrade our cities to be the kinds of compact, walkable, affordable places where extra people enliven our communities rather than clogging our highways.

Besides, if you take the threat of climate change seriously and open your mind to the possibility that change can be good, you may start to see that more people wanting to live among us could be a blessing, not a curse. Thanks to them, Cascadia can speed the urgent transition beyond carbon. Decarbonizing an emptying city in the grips of disinvestment—think of Detroit or St. Louis—is like trying to sail the doldrums: no matter what you do, you just drift with the current. In contrast, a local boom at least lets you chart your course toward decarbonization. The waves may give you a bumpy ride, but you can steer where you choose.

A surging economy lets us fill our landscape with new homes and workplaces and erect them according to the principles of green design: super-efficient, zero-emission buildings and transportation, energy, and water systems. In town, we can upgrade to bike lanes and electric scooters, better transit, zero-energy buildings, rain gardens and walkability. Outside of town, we can transition to fast intercity electric trains, regenerative farming and forestry, and solar and wind arrays. Local growth makes it possible to achieve beautiful, vibrant, convivial urbanism. It also brings challenges, of course: many of them, from the loss of quiet to the increase in traffic, from the loss of familiar landmarks to the strain to upgrade infrastructure in step with rising demands. The most raw and infuriating challenge of growth may be the displacement, through rent escalation, of people of color from neighborhoods into which they or their predecessors were shunted by racial and ethnic covenants, redlining, and other forms of discrimination. These neighborhoods, if disadvantaged and too-often neglected by public agencies, have nonetheless been the homes assigned to many people of color by society, through its often-invisible systems of power and privilege—legal, economic, cultural, and behavioral. Residents of neighborhoods of color may deserve recompense to benefit fully from whatever good fortune growth brings. Too often, though, they benefit the least or indeed suffer. Sometimes, they are left no choice but to move away, as newcomers bid up housing prices. The best responses to this tragic dynamic, which I’ll address in a future article, aim to give a modicum of control to such neighborhoods, without worsening the housing shortages that speed their displacement. Local growth can provide the resources that enable such strategies.

What a housing-abundant, low-carbon future looks like

The crux of the climate challenge for cities is building dramatically more homes in close-in areas—everywhere within perhaps ten miles of the city’s business core. These places are the most sought-after and lowest-carbon addresses, places that should sprout hundreds of thousands of dwellings in taller buildings—some of them high-rise towers, where rents will support the construction costs, but most of them cheaper mid-rise apartments of perhaps eight floors, alongside low-rise rowhouses and walk-up apartment buildings. Even allowing such mid-sized buildings on a tenth of the lots currently reserved for detached houses would generate staggering amounts of new housing.

Taking Cascadia’s climate commitments seriously means settling several times more people per acre into our urban cores. Done right, this imperative need not be a sacrifice but can be an opportunity: we could, for example, turn Portland into a stunningly beautiful city like Vienna, Seattle into a gem like Paris, and Vancouver, BC, into a model of walkability like Barcelona.

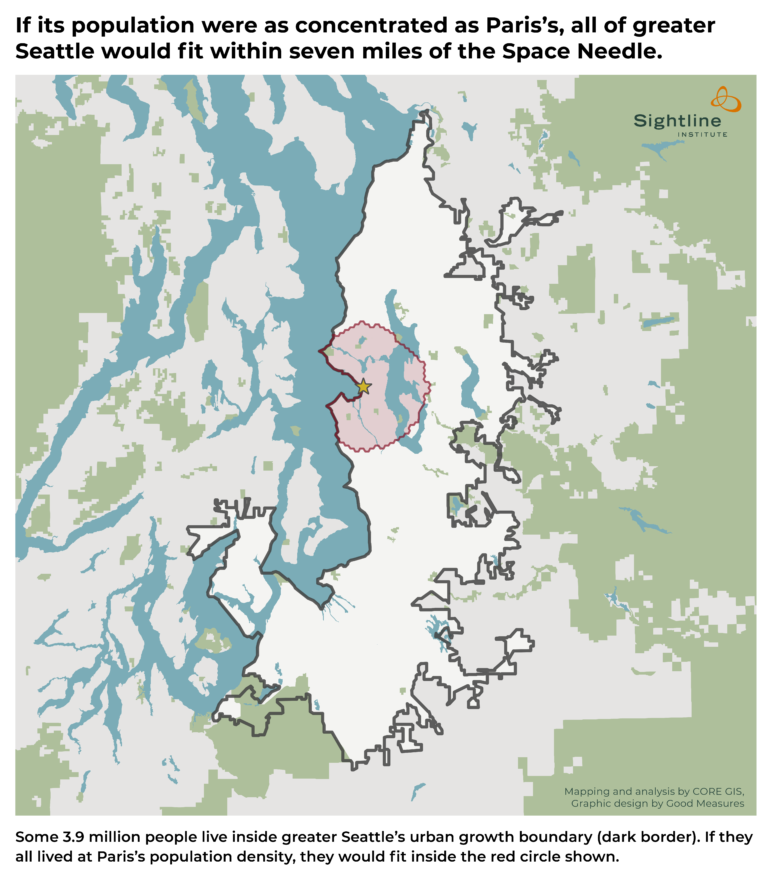

In the map below, you can see what greater Seattle’s developed area would be if it approximated the density of Paris. North Americans love Paris: more than 2 million Americans fly across the ocean to visit it every year, outnumbering visitors from any other nation and matching the population of the City of Light. And if Seattle looked like Paris and Seattleites lived like Parisians, the entire Seattle metropolitan population of 3.9 million would fit comfortably within a seven-mile radius of the Space Needle, almost entirely inside city limits. I’m not suggesting we actually abandon the Puget Sound suburbs. But as the never-ending and sometimes disorienting process of urban rebirth continues, it can help to have a vision in mind. How about envisioning Seattle’s future as Paris on Elliott Bay?

Original Sightline Institute graphic, available under our free use policy.

The process of growth and change in Cascadia’s cities seems unlikely to slow. It may speed. Cascadia’s three major metro areas have doubled in population in the last four decades, and that pace was before widespread acknowledgment of climate change. Think about the recent, early signs of climate chaos: the wildfires in Australia and California, the floods in the Midwest and Southeast. Consider that rising seas will likely displace tens of millions of people worldwide. Cascadia’s destiny as a climate refuge is all but assured.

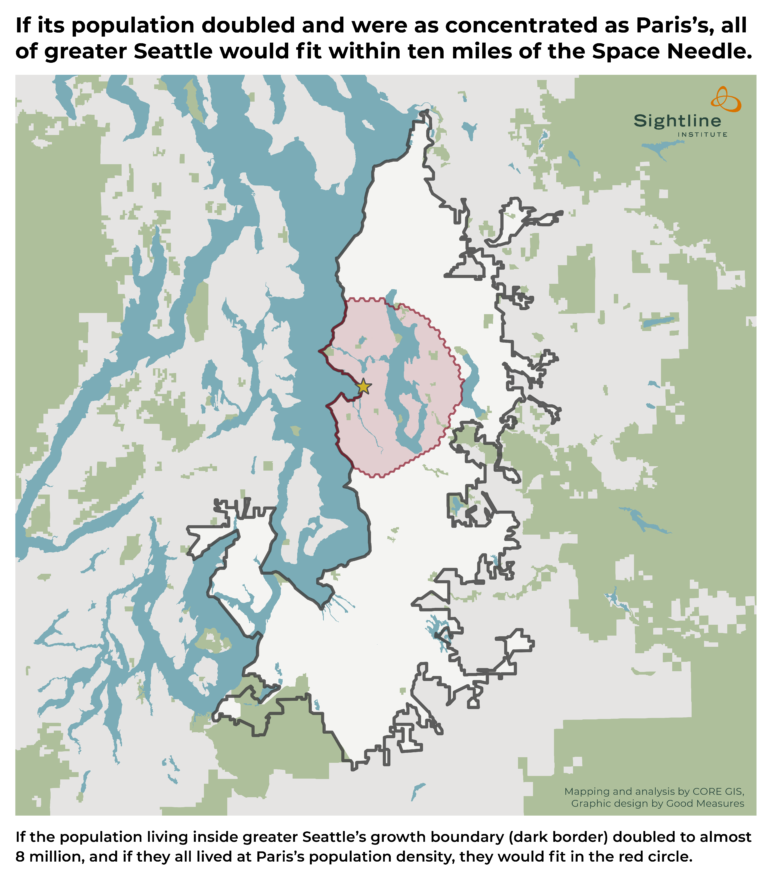

If the greater Seattle area’s population doubled to almost 8 million, and if these people all lived at Parisian densities, they would need as much land as is shown in the map below. It’s more than is needed for Seattle’s current population, but not by much. The edge of the metro area would be within ten miles of downtown.

Original Sightline Institute graphic, available under our free use policy.

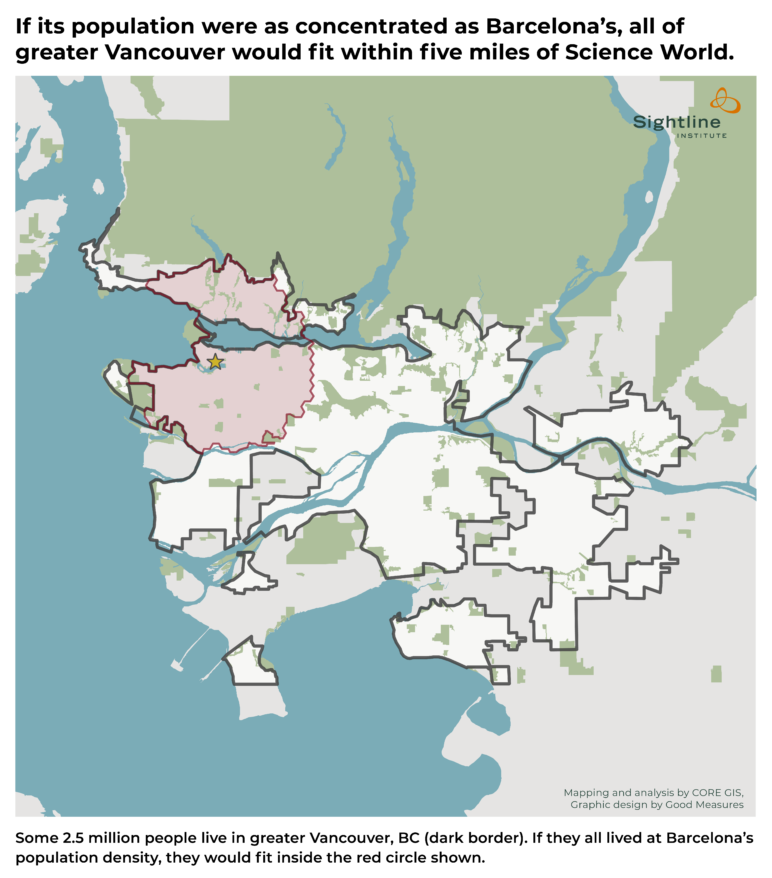

The same reasoning applies to Vancouver, BC, and Portland. In the map below, you can see what greater Vancouver would look like if its population were distributed in the manner of another of the world’s most admired cities: Barcelona.

Original Sightline Institute graphic, available under our free use policy.

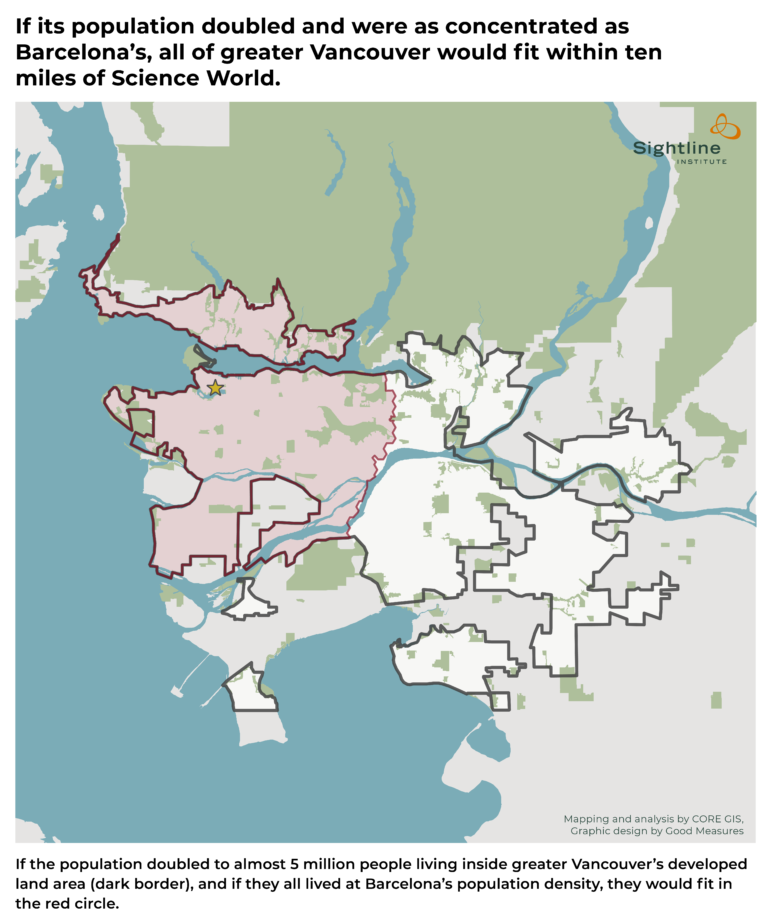

The map below shows how much land would be needed if greater Vancouver’s population doubled and its residents lived as do the people of Barcelona—in magnificent blocks of mid-rise apartment buildings with landscaped courtyards.

Original Sightline Institute graphic, available under our free use policy.

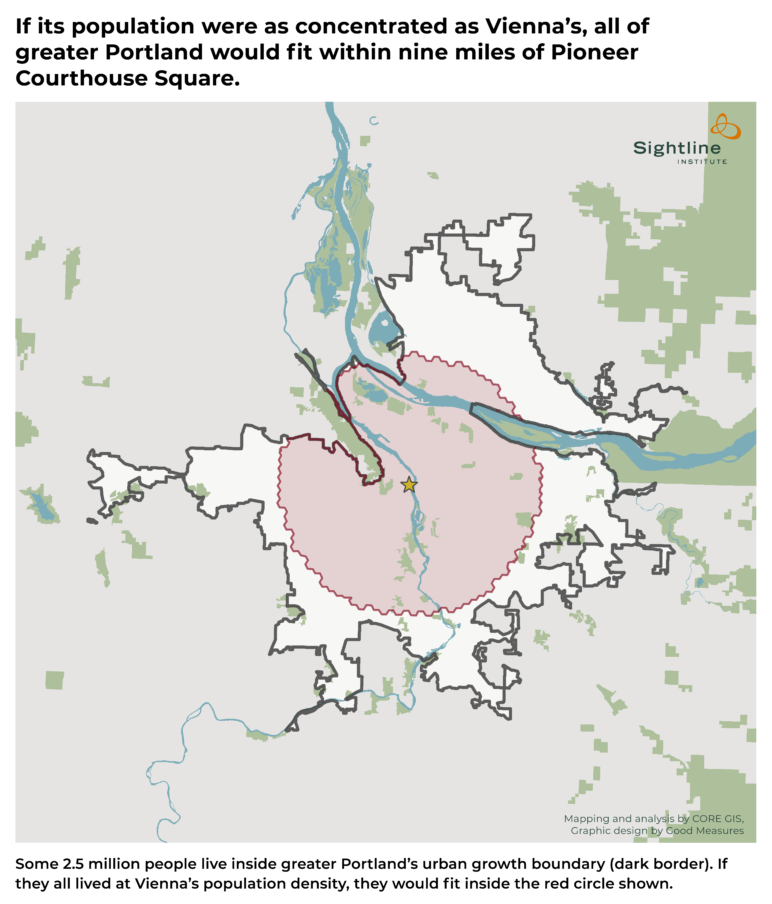

Finally, below is what greater Portland would look like if it matched Vienna’s population concentration, which is considerably lower than that of Paris or Barcelona but still almost double the density of today’s Portland. Vienna is a city of small and large apartment buildings set in more parkland than exists in any Cascadian city.

Original Sightline Institute graphic, available under our free use policy.

In each case, Cascadia could welcome many additional people to our great cities on a fraction of currently developed area if we let ourselves grow more like these European models. Again, these maps are not proposals or growth plans; they’re illustrations of the proposition that Cascadia’s metropolitan areas could sustain or improve their livability while growing toward much closer concentrations of residents.

We can not only fill our cities in. We can also build them to the highest standards of energy efficiency. We can free ourselves of fossil fuels, converting our buildings and much of our transportation to all-electric energy, and derive our electricity from net-zero emission sources. We can also retrofit our cities for resilience to a changing climate. We can prioritize in our plans neighborhood integration by class, race, ethnicity, ability, and age, through investments in subsidized housing and community stabilization programs. We can improve our verdant infrastructure of parks, public spaces and other shared amenities. We can build community, strengthen cultural institutions and the arts, and integrate education and beauty into our neighborhoods. And we can continue to be places of innovation, enterprise, and economic opportunity.

The pace of change may be bracing, but it will not be unfamiliar to Cascadia’s residents. Edifices wear out; we replace them. Compared with many other metros, Cascadia’s big cities have been on a tear for years. Change is constant, the question is what change will come? What will we replace our buildings with? Will we continue to build what our parents got us accustomed to: exclusionary, overpriced sprawl that is baking the planet? Or will we build what our children urgently need: welcoming, affordable, compact, walkable, zero-emissions cities? Paris on Puget Sound, Barcelona on Burrard Inlet, Vienna on the Willamette?

Next time: The omnipresence of housing shortage.

Margaret Staeheli

I am waiting for Sightline to dig deeper and show we can have robust dense house housing a viable large urban trees on each block. The right of way is not wide enough for canopy and adequate root zone- some portion of the parcel is needed to accommodate trees and provide climate adaptive walkability.

You write “ In town, we can upgrade to bike lanes and electric scooters, better transit, zero-energy buildings, rain gardens and walkability. “ Where are the urban trees? They are not being given space in your research and writing nor current construction.

Sherri Schultz

Check out Guerrilla Developments new Tree Farm building in Portland sometime — it has 72 trees ON the facade! http://guerrilladev.co/tree-farm

Alan Durning

Margaret,

Thanks for your note — and your work on green infrastructure. But your critique is unfounded.

We’ve devoted thousands of words to integrating trees and other green infrastructure into our cityscapes. Here are three recent examples:

https://www.sightline.org/2018/09/06/seattle-trees-development-not-a-tree-apocalypse/

https://www.sightline.org/2018/09/14/portland-housing-infill-and-tree-infill/

https://www.sightline.org/2017/05/15/stormwater-management-lessons-from-our-forests/

Besides, as noted, Vienna, in particular, has vastly more green space than any NW city, plus twice as many people per acre.

Alan

Mary Duvall

I see all that concentration around the coast line which, if climate change models are accurate, will be under water….bigger picture needed…it won’t just be hotter, there will be less land along all the waterways…and the space needle will be floating.

Maybe Venice should be the model.

Alan Durning

As I wrote: “These maps are not proposals or growth plans; they’re illustrations of the proposition that Cascadia’s metropolitan areas could sustain or improve their livability while growing toward much closer concentrations of residents.”

C Jones

Let’s stay focused on reality, please, Mary Duvall. The Space Needle is at an elevation of 125 feet above sea level. If all of the ice on earth melted (which is not in anyone’s modeling projections), sea level would rise only about 230 feet (70 meters). The Pacific Northwest’s topography, unlike that of some large east coast cities, makes us a climate refugee destination precisely because we have plenty of room for European-style density and vibrancy even with a little sea level rise.

Sherri Schultz

Thank for this epic call to action (as Eugene citizens work to revise the woefully inadequate draft Climate Action Plan the City took two years to compile). Those maps are mind-blowers!