As the Alliance of Californians for Community Empowerment wrote in a powerful report Thursday, Californians suffer from an unprecedented housing crisis.

California’s colossal housing shortage is made worse, ACCE said, by the fact that several hundred thousand units are empty and currently unavailable for sale or rental. In at least some cases, that’s probably because their owners plan to ride the wave of rising prices that the state’s long-term shortage will continue to induce. The report and ACCE’s accompanying campaign emphasize the horrifying fact that Los Angeles in particular has more “non-market vacant” units than there are Angelenos experiencing homelessness on any given night.

ACCE is pushing for new taxes on long-term vacant homes, partly inspired by the one in Vancouver, BC. If a city has a high number of mostly-vacant “investment” properties, it’s a reasonable proposal.

But there’s an even bigger injustice this report overlooked, as do most of the similar exercises about empty apartments that circulate now and then.

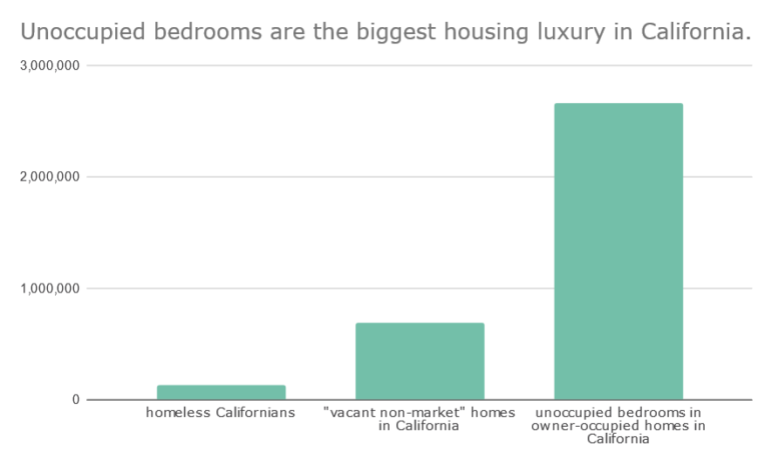

It’s true that for 2013-2017, the Census estimates 691,343 totally empty homes in California, including plenty in condo buildings, that ACCE categorizes as “off-market” because they’re either “for seasonal, recreational or occasional use” or otherwise unavailable to rent or buy. This is, disturbingly, more than five times the estimated 129,972 homeless Californians.

It is equally true that even if every adult and every child in one of California’s owner-occupied homes required a bedroom of their own, the state would have 2,660,505 bedrooms where no one sleeps—20 unoccupied bedrooms for every homeless Californian.

One of these inequities is much, much larger than the other.

Not only is California failing to disincentivize this second, larger injustice. In this case, it’s actually subsidizing the injustice with hundreds of millions of dollars every year in the form of California’s cap on property taxes for longtime property owners, which swells the price of housing for anyone not lucky enough to already own.

Not only is California failing to disincentivize this second, larger injustice. In this case, it’s actually subsidizing the injustice with hundreds of millions of dollars every year in the form of California’s cap on property taxes for longtime property owners, which swells the price of housing for anyone not lucky enough to already own.

This isn’t a call to disregard ACCE’s valid criticism of how some homes, including some in condo towers, can sit empty while humans struggle to survive outdoors. (ACCE later pulled the report from its website over problems with a mostly unrelated section of the project that looked specifically at recently constructed buildings; I don’t discuss that problematic section in this article.)

But for Californians (and for Cascadians playing out similar debates) it’s worth asking: Why does the smaller of these two inequalities seem to persistently get more political attention than the bigger one?

And who benefits as a result?

The renter’s shortage, the owner’s surplus

Forty-five percent of Californian households have no such surplus of space: the 45 percent who rent their homes.

Unlike with owned bedrooms, California doesn’t have enough rented bedrooms for every renter. Even if you were to assume that Californians share bedrooms at the same rate as British Columbians (Canada has more precise data on bedroom sharing) only about 4 percent of tenant bedrooms in all of California are unoccupied at night.

In housing-scarce Los Angeles, home to ACCE, things are even tighter for renters: they’ve got fewer bedrooms per person even than British Columbian tenants. And one bedroom per tenant is a distant dream for Angelenos. To do that, the city would need 20 percent more rental bedrooms.

This is how a housing shortage affects its losers: they squeeze tighter and tighter together if they can find anything at all.

Not so in the Los Angeles ownership market, which has about 90,000 more bedrooms than Angelenos. If Angeleno homeowners are sharing bedrooms at BC homeowner rates, it’s more like 160,000 bedrooms, 11 percent of the total owned bedroom count. That’s compared to (in the 2013-2017 Census data) about 46,000 totally vacant “off-market” homes in Los Angeles and 36,000 Angelenos without homes.

Most of these unoccupied bedrooms, of course, have been rising rapidly in value, thanks to the state’s continuing failure to build enough total homes to keep up with job and population growth.

The market price of housing varies wildly by state and (because more than 75 percent of low-income Americans live in market-rate housing*) correlates directly with the rate of homelessness.

What’s to be done?

No, I don’t think it would be a good idea to appropriate every guestroom in Orange County and house homeless people in them. ACCE isn’t calling for empty condos in Beverly Hills to be seized, either. (Satisfying though that might be in some cases.)

Instead, like ACCE, Californians and Cascadians and everyone else should look for structural changes—economic dikes and sluice gates that would channel our wealth away from waste and toward voluntary, abundant sustainability.

In addition to continuing to raise and spend money for below-income housing, we should do things like re-legalizing shared homes, lifting the apartment bans in low-density, job-rich enclaves of San Jose, subverting speculation with community land trusts and reforming California’s monumentally terrible property tax system that systematically transfers wealth from young to old, migrant to incumbent, brown to white. All these things would lower the costs of finding a stable home in California.

And in the meantime, I hope that when we use housing inequality to focus on the need for change, we don’t overlook the single biggest form of luxury in our housing market: big detached homes whose residents aren’t even really using all the space.

* This is a conservative estimate based on 2012-2016 Department of Housing and Urban Development data, the most recent available, and the 2015 American Housing Survey. Adding all households in HUD-subsidized rentals together, and assuming that all US households in subsidized housing are low-income, suggest that at most, 14 percent of all low-income households could be in HUD-backed housing. The 2015 American Housing Survey estimates that 7.2 million units in the US are subject to government rent reductions, including state and local programs; this is 23 percent of low-income households. (I considered a US household “low-income” if its income was less than half the median calculated for its area, as tallied nationwide in HUD’s Comprehensive Housing Affordability Strategy data. Many state and local programs subsidize people with somewhat higher incomes, so this 75 percent figure is probably an underestimate.)

Hello Human

From reddit:

“A person’s choice to drop out of society, take illegal drugs, not take the drugs he should be taking, not live in a place where he can afford, etc. has no bearing on the sovereignty of my bedrooms.” -WasteElk

Get off your high horse

Michael Andersen

If your takeway from this post is that you personally have a moral obligation to take a poor person into your spare bedroom, you should (a) consider it, but also (b) reread the last section!

The fact in the headline is an indication of the scale of inequality, not a policy proposal. If we want to start solving the problem it describes, we should stop subsidizing size, penalizing and/or banning shared homes, smaller homes and cheaper homes, bring down the cost of new construction, and of course spend public money to keep poor people housed.

I have no problem with your choice to have a spare bedroom, only with our choice as a society to subsidize that choice.

Scott Cox

A lot of good thoughts here, but you’re missing one of the key reasons for larger homes with more bedrooms. Tap, impact, connection and other fees in California are enormous. And they are per unit, not per SF. How would a builder be expected to build a small cottage when fees can approach $100K per unit and are are almost never less than $40K? If want smaller homes, you’ll have to tackle this problem.

Michael Andersen

Good points!

Ansel Lundberg

Great piece! Thank you for writing it.

Boris Karlof

Rules for thee,

But not for me

You just cant seem to grasp the fact that most homeless people have addictions, add to this mental health and very bad transmissable deseases.

How they got there, Im not their judge. But you baffoons who make everything a sociology experiment need to use some common sense.

1 Many states have empty hospitals or old schools that can be repurposed to accomodate homeless people..

2 These can be used to house,

Feed, and most importantly

Rehabilitate these poor souls

3 It may look like this:

An individual is sent in lieu of serving jail time for a crime committed ( no felonys)

Most steal, or vandalise

Or they voluntarily sign up.

4 There they will serve a 9 -12 month program that will include the following;

1.Drug rehab,

2.Intensive counseling :

3.Drug, Mental health,

4.And learn a trade.

So that when they leave they will be able to reenter society

And feel useful and have a sense of accomplishment.

Because what you are doing now is idioacy.

And very unsafe for ALL.

Max Ghenis

This paper has been retracted. Why is this article still up? https://laist.com/2019/11/20/los-angeles-housing-vacancy-homeless.php

Michael Andersen

Because the issue that I understand led to the retraction – the vacancy rate in a comparatively small number of very recently opened buildings – isn’t discussed here, and doesn’t invalidate anything about the numbers that are cited here.

Lee Sawatzki

In 1910, half of households rented out bedrooms (see Living Downtown); but the number is marginal today. Alternatives to apartment-renting, such as the boardinghouse, petered out after the 1968 Fair Housing Act. Most homeowners are leery about letting “strangers” into their home, but are more comfortable renting to someone of their own background (education, religion, and so forth). But room-letting is still common among middle-class members of ethnic communities, who advertise in non-English newspapers and groceries. Language is therefore used as a filter to select tenants.

We need to bring the boardinghouse back into the mainstream. I understand that Whites are more likely to own homes, but Blacks are more likely to rent out bedrooms, as several of my neighbors are doing. This balance should provide equal access to affordable lodging.

Kaptain

Reasons for homelessness in the US as of 2021:

31% job loss

20% drugs or alcohol use

15% divorce or separation,

13% an argument with a family member who asked them to leave

7% domestic violence.

10% eviction

7% mental health

7% physical health or medical condition.

12% incarceration

1% housing restrictions due to probation or parole.

MORE HOUSING ONLY FIXES A VERY SMALL PORTION OF THE HOMELESS ISSUE. Also, and I know this is a hard pill to swallow, the largest population of homeless are white. This is not a Black Or Hispanic issue, any more than it’s a white issue. So let’s take race out of this argument. I know it’s inconvenient.

It’s time to stop beating the drum of not enough housing then, as the quick fix for all that ails our society.

Michael Andersen

But most people who go through those situations do not become homeless, so there must be other factors at play, too.

Every situation is unique, but (because we will not end job loss, divorce, etc) we should fight homelessness in part by helping more people be more resilient to the situations you mention (and to other slings & arrows).

At the metro area level, no factor predicts homelessness rates better than housing prices. To me, this suggests that making housing less scarce – increasing the chances that someone the potentially homeless person knows has an empty bedroom, or increasing the chance that they can quickly find a new place they can afford – is a major way to fight homelessness.

None of this means that more housing is a quick fix. It isn’t. It’s a slow but important one.