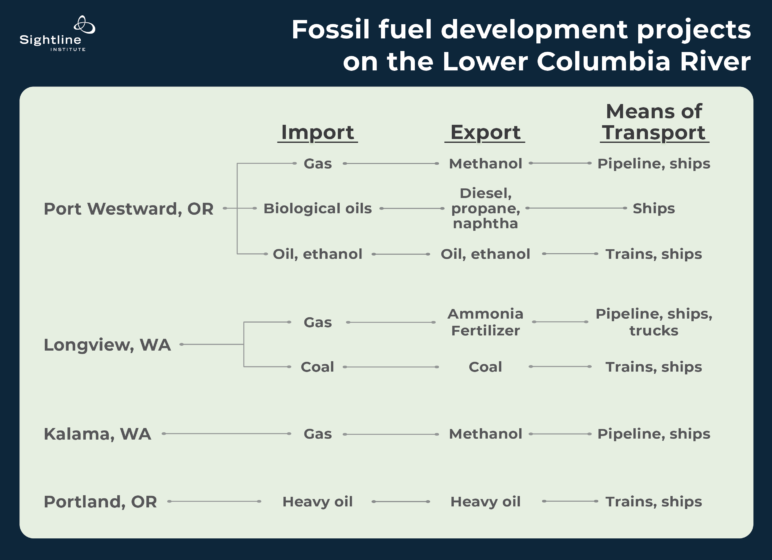

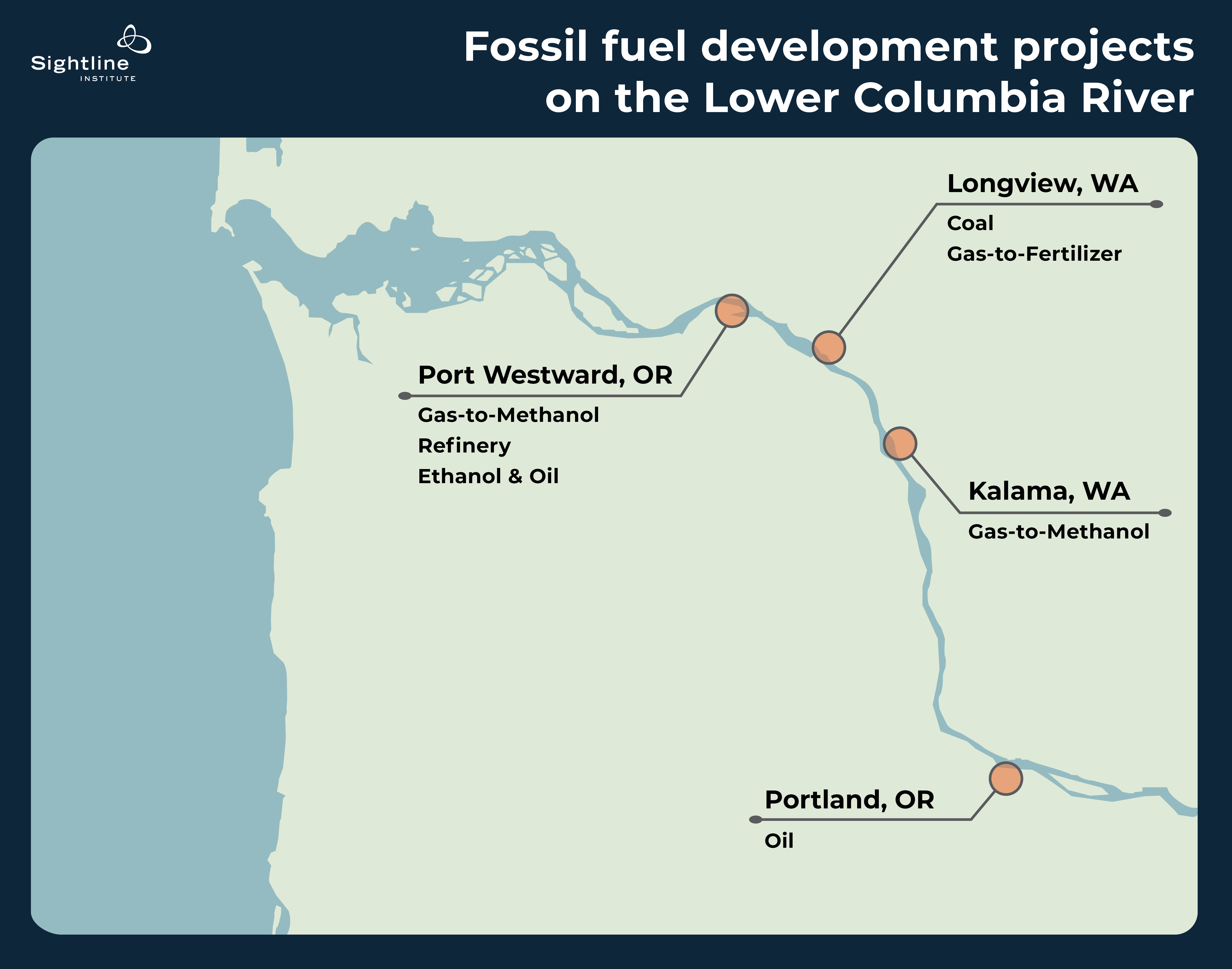

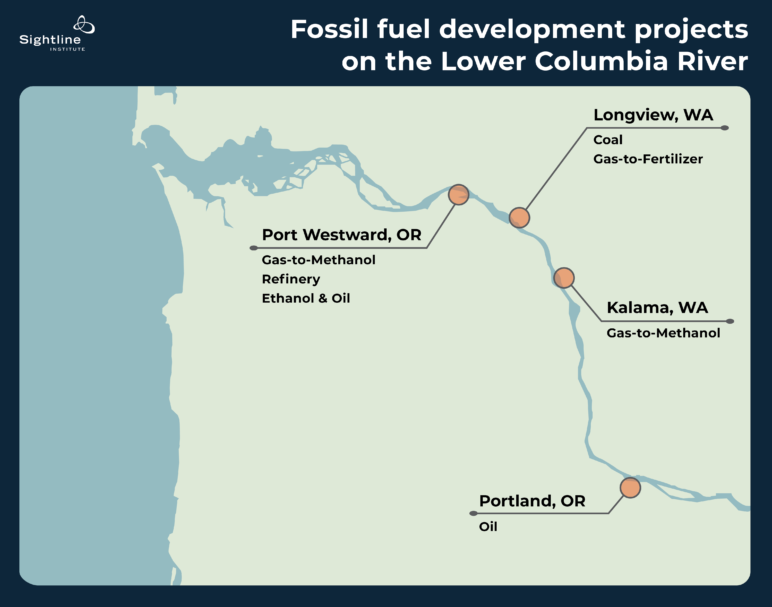

In all the Pacific Northwest, the Lower Columbia River is the most vulnerable to the threat of fossil fuel expansion. In one 50-mile stretch along the region’s biggest hydrological artery, there are no fewer than seven active proposals to bring, refine or handle coal, oil, gas, or other fuels before shipping them to markets elsewhere.

The Northwest’s opposition movement to fossil fuels—the Thin Green Line—has turned back dozens of proposals to build infrastructure for shipping dirty energy products. In fact, many of the movement’s biggest successes have been on the Lower Columbia River, where tenacious locals’ resistance has stopped projects like a massive LNG export facility at Astoria, Oregon and a huge oil-by-rail terminal at Vancouver, Washington. Still, a small number of communities on the Lower Columbia River remain targets of the fossil fuel industry.

To understand what’s at stake for Lower Columbia and this part of the Northwest, it is useful to examine these communities and the proposed projects there in some detail.

Original Sightline Institute graphic, available under our free use policy.

KALAMA, WASHINGTON

Gas-to-methanol production and exports

A Chinese government-backed company called NW Innovation Works is pursuing permits for a massive petrochemical production facility and export terminal in Kalama, Washington. The facility would be the largest gas-to-methanol plant in the world, producing 3.6 million tons annually for export to China in 36 to 72 oceangoing vessels. In China, the methanol may be used in the production of olefins, a precursor to plastics manufacturing, as well as fuel for cars. In addition to the gas-to-methanol plant, the project includes three other closely-related developments: a marine export terminal, a new 3.1-mile pipeline segment, and upgrades to electrical transmission lines.

The company claims that the project would result in a net reduction of global greenhouse gas emissions, but these assertions are backed by dubious assumptions and do not stand up to scrutiny. In reality, the Kalama plant risks locking in technologies and fuel sources that are incompatible with an effective transition to clean energy and would tie up large quantities of hydropower that could be used for other purposes. Moreover, the project would enjoy nearly $150 million in taxpayer subsidies.

Washington Governor Jay Inslee laid the groundwork for the plant during a 2013 trade mission to China and offered support for the project in a January 2015 speech. But Inslee reversed course and publicly opposed the project in May 2019, citing the evolving science of methane’s harmful effects and the growing urgency of addressing the climate crisis.

Read more: Calling Natural Gas a ‘Bridge Fuel’ is Alarmingly Deceptive

In September 2017, the State Shorelines Hearing Board revoked two key development permits, pointing out that the greenhouse gas emissions related to the entire production process were missing from the original Environmental Impact Statement report—a key to fully account for the project’s costs to the region’s climate goals. About a year later, the Port of Kalama attempted to address the shorelines board’s concerns by releasing a draft Supplemental Environmental Impact Statement. The Port of Kalama and Cowlitz County are still preparing the final Supplemental Environmental Impact Statement. NW Innovation Works hopes to begin construction in 2019 and methanol production in 2023.

PORT WESTWARD, OREGON

Port Westward on the Lower Columbia is a 1,700-acre industrial park owned by the Port of Columbia County, about five miles north of Clatskanie, Oregon. At present, the site hosts a Portland General Electric gas-fired power plant and several operating or proposed fossil fuel projects. Since 2012, the Port has been attempting to rezone agricultural land on the site for industrial use in order to facilitate expansion, but that rezone has been tied up in ongoing legal appeals and will likely not be sorted out before 2020.

Ethanol- and oil-by-rail export

Global Partners LP operates the Columbia Pacific Bio-Refinery, a rail-to-marine ethanol terminal at Port Westward (though the refinery does not operate). The company in June 2018 won state approval to acquire nine old oil storage tanks with a combined capacity of 1.2 million barrels from PGE, aiming to refurbish them for ethanol.

Many recall that the company was transloading crude oil at the site as recently as 2017 and worry the site will revert to an oil export terminal. In fact, the company recently got permission from the port commission to handle petroleum products with a lower API gravity, which would allow the firm to ship heavy crude oil (though probably not tar sands oil).

Renewable Diesel Plant and Marine Terminal

NEXT Energy Group, a subsidiary of Waterside Energy Development, is aiming to build a billion-dollar renewable diesel refinery at Port Westward. The facility would annually produce up to 13.3 million barrels of mostly renewable diesel from feedstocks that include cooking oil, animal fat, and various plant oils. It would also produce smaller quantities of propane and naphtha. Both the feedstock and the refined products would arrive and depart via the marine terminal at Port Westward on large ocean-going vessels, with deliveries of refined products predominantly destined for other West Coast ports. A spokesperson for the company claims that “the facility will only be permitted and built to process renewable feedstock,” and that “no fossil fuels will be processed or produced.”

Waterside Energy CEO Lou Soumas has been linked to shady dealings with similar projects, including failing to provide evidence of sufficient financial backing for a proposed oil refinery in Longview and abandoning a biodiesel plant in Odessa, Washington without paying for cleanup or outstanding taxes. Waterside also backed a liquefied petroleum gas project at the Port of Longview that was rejected by the port commission.

The Port of Columbia County approved a site development agreement in September 2018, though a formal lease agreement for the 94-acre parcel cannot be signed until the land-use appeal is settled. NEXT Energy also recently acquired a neighboring property, with hopes of starting construction by the summer of 2019 in order to have the plant fully operational by 2021. NEXT Energy announced in February 2019 that it got a purchase agreement with Shell Oil for the renewable diesel.

Methanol Production Plant and Export Terminal

NW Innovation Works, the same company behind the proposed Kalama methanol facility, was leasing 82 acres of empty land at Port Westward, where the company hopes to build a methanol plant on the Lower Columbia much like Kalama. But the Port Westward proposal has not yet begun the process for obtaining necessary construction and operation permits from the state, nor has the project undergone environmental review. Port officials admitted in February that plans for the plant have not gained traction and NEXT Energy has discussed taking over the leasehold from NW Innovation Works.

In June 2019, a spokesperson for the Port confirmed that NW Innovation Works had given up their lease option for land at Port Westward with the land offered to NEXT Renewable Fuels in a Site Development and Option Agreement. NW Innovation Works now has a Site Development and Option Agreement with the Port in the area proposed for a rezone.

PORTLAND, OREGON

Oil-By-Rail Export Terminal

Zenith Energy is located on the banks of the Willamette River in the northwest corner of Portland. The Portland site includes 84 bulk liquid storage tanks with a combined storage capacity of more than 1.4 million barrels. There’s also a terminal capable of receiving and transloading “heavy and light petroleum products” from trains and Panamax-sized ocean-going vessels. Pressure to find export routes for Canadian tar sands oil precipitated a surge in oil-by-rail shipments that reached 300,000 barrels per day by the end of 2018. The Zenith terminal represents an important way station for Canadian tar sands oil en route to Asian markets. At least some of that oil-by-rail has been transloaded onto vessels at the Portland Zenith terminal, where three shipments of about a quarter-million barrels each had sailed to China as of May 2018.

The company has even larger ambitions: crews are building three new rail platforms that will nearly quadruple the 39-acre site’s previous capacity for offloading oil from tank cars. Once complete, the terminal could handle nearly 100 oil trains per year.

The site is particularly galling to many Portland residents who are proud of the city’s ban on fossil fuel projects, which is probably the most stringent in the nation. Unfortunately, the Zenith project secured permits before city leaders voted on the ban. Worse yet, Oregon’s comparatively lax laws on oil trains have left state regulators in the dark about how much tar sands crude has been moving to the terminal. Serious safety hazards are already looming due to lack of oversight: trains carrying crude oil with high levels of hydrogen sulfide, a chemical that can be dangerous to first responders, rolled through Portland for weeks before the Oregon Department of Environmental Quality discovered it.

LONGVIEW, WASHINGTON

Pacific Coast Fertilizer

Pacific Coast Fertilizer wants to build and operate a facility that would process gas to manufacture anhydrous ammonia, a popular nitrogen fertilizer with a notable risk profile. The City of Longview, which sits near the northeast banks of the Lower Columbia, is developing a draft Environmental Impact Statement examining the project’s potential impacts on air and water quality, climate change, and more. The draft EIS will likely be released for public comment sometime in mid-2019.

Millennium Bulk coal exports

The proposed Millennium Bulk coal terminal in Longview would be the largest coal terminal on the West Coast of North America, but it seems well and truly dead after the Washington Department of Ecology denied permits for it, citing nine instances of significant and unavoidable harm if it went into operation.

A federal judge rejected an appeal from the project backers, who tried to argue that by denying the permits the state was interfering with the federal government’s ability to regulate foreign affairs. But the company has one remaining legal Hail Mary: the company intends to argue that the permit denial illegally pre-empted the interstate commerce clause of the Constitution.

The company has also appealed the permit decision itself to the State Pollution Control Hearings Board, but meanwhile, the economic outlook for coal exports has imploded.

This article was updated on June 18, 2019, to reflect the number of projects and clarify the kind of fuel produced in Port Westward.

Thanks to Maithili Joshi, Aven Frey, John Abbotts, and Paelina DeStephano for research contributions.

Ahren Stroming is a research contributor to Sightline. He’s a former policy analyst for the City of Seattle Office of Sustainability and Environment and a graduate student at the University of Freiburg in Germany.

Eric de Place is Sightline’s Director of Thin Green Line and he spearheads our work on energy policy. He is a leading expert on coal, oil, and gas export plans in the Pacific Northwest, particularly on fossil fuel transport issues, including carbon emissions, local pollution, transportation system impacts, rail policy, and economics. He has researched and published more than four hundred articles, reports, and analyses on these proposals. For questions or media inquiries about Eric’s work, contact Sightline Communications Manager Anne Christnovich.

Diane Dick

Thank you Eric and Sightline. Sometimes large battles are fought in small places.