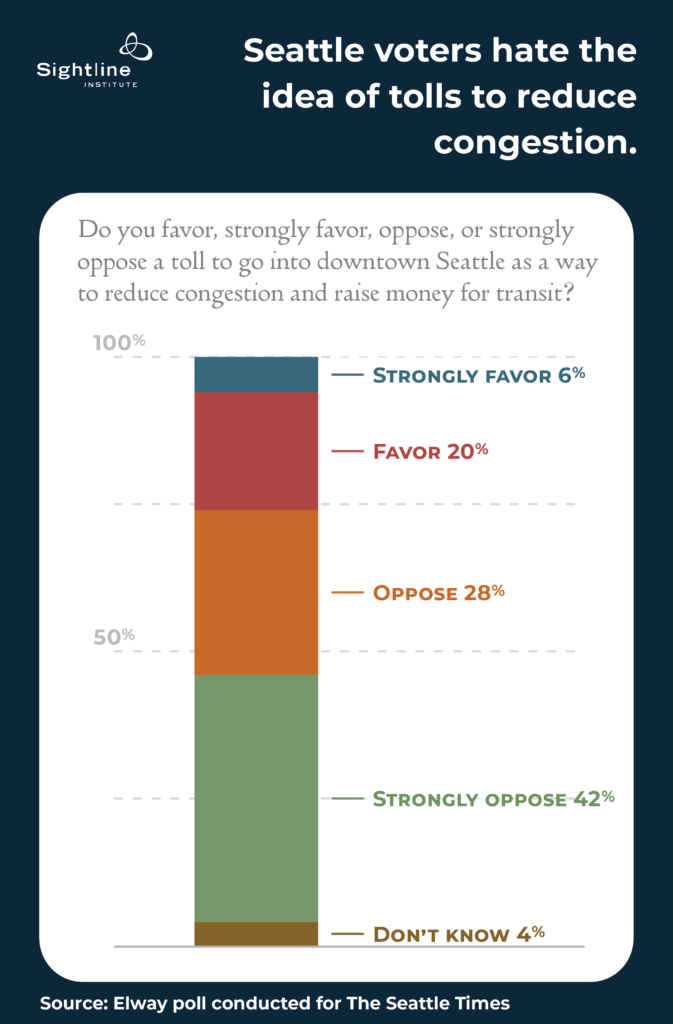

The Seattle Times recently tested public opinion on the idea of imposing tolls to reduce congestion and, oh my, people hate it! In January, the Times reported that 70 percent of voters in Cascadia’s biggest city oppose or strongly oppose “a toll to go into downtown Seattle as a way to reduce congestion and raise money for transit.” Polling numbers like that might cause an ambitious politician like Seattle Mayor Jenny Durkan to reconsider her support for the idea.

Original Sightline Institute graphic, available under our free use policy.

Let’s hope the Mayor and her new transportation director, Sam Zimbabwe, stick with it. Public opinion can shift markedly as people learn more about how new public policies actually work. Take Obamacare, for example. In November of 2013, just 33 percent of US voters had a favorable view of the Affordable Care Act, but by January of 2018 that number was up to 54 percent according to the Kaiser foundation. As Obamacare came under attack by a Republican congress in 2017, the public came to more fully appreciate how the ACA made them better off. To the extent that congestion pricing would also make commuters better off, perhaps enlightened political leadership in Cascadia can turn today’s naysayers into future supporters.

It’s happened before. Public opinion on congestion pricing in Stockholm went from 70 percent opposed to 70 percent in favor after the city implemented a pilot program that put a new toll on vehicles entering the downtown core. For a quick look at how it works in Stockholm, check out the short video below with the city’s Transportation Director Jonas Eliasson.

The city ran a seven-month pilot and then held a vote. Stockholm voters chose to keep the program in place because it had eliminated crippling congestion. They were happy with how the city was spending the toll revenue.

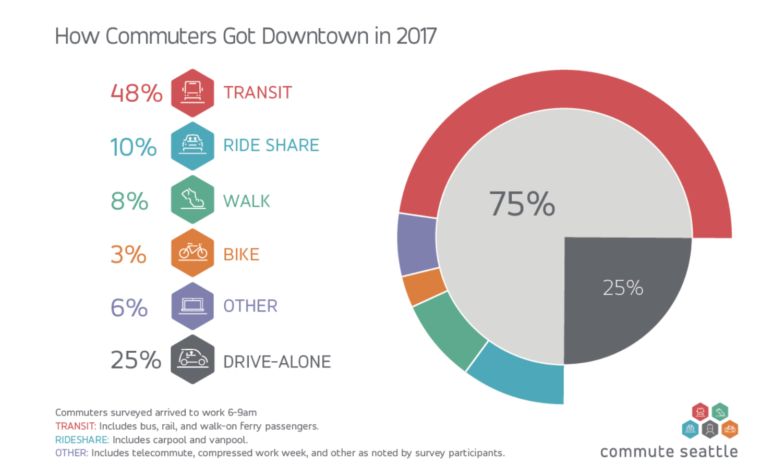

The same opportunity for widespread support exists in Seattle. Commute Seattle surveyed people arriving in the downtown core between 6-9 am in 2017 and learned that 75 percent of them arrive by a mode other than driving alone. Nearly half use public transit and every one of those commuters would be better off with a congestion pricing program: their out-of-pocket costs would stay the same, their commutes would be faster and more reliable. If some of the revenue supported improved transit, they might even enjoy more frequent service.

Rideshare commuters would also benefit from faster and more reliable travel times in a future with efficient pricing. They would have to pay a new toll but they could share the charge with multiple riders so, for most, the reductions in travel time and risk of long delays would more than make up for the increased dollar costs.

Walkers, bikers, and other commuters would all win with less noise, emissions, and accident risk that would result from having fewer cars on the road. Some portion of the 25 percent who drive alone would also be better off to the extent that they value the time savings and increased reliability more than the dollar value of the toll.

For some fraction of the 25 percent, however, the toll costs would cause them to stop driving alone and choose a new option. If the revenue from tolling were used to provide improved transit service, some of those commuters might also be better off after switching from private cars to public transit.

Knowing such a large share of commuters could come out ahead should keep Mayor Durkan and her team on the task of designing a sensible tolling regime that makes most people better off. In a well-designed plan, the revenues must be put to good use and the tolls must be high enough to reduce congestion during peak periods and then drop outside the commuting hours.

Travel in and out of Seattle in off-peak hours normally involves very little congestion so any toll would need to be correspondingly low or non-existent. Varying the tolls by time of day would mitigate the concerns of downtown retailers who reasonably worry that tolls might keep away shoppers. If the tolls drop to zero from 9:30 am to 3:30 pm on weekdays, then travelers with more flexible schedules can get in and out at the same cost they do today.

Commercial vehicles and Uber and Lyft drivers would all benefit from a pricing plan that lowers congestion. For these drivers, time is money, and reduced congestion means higher revenue and lower operating costs. Those improved economics would more than cover the cost of a congestion toll.

And yet, if asked, most people oppose the idea of adding congestion-based tolls. In cities across the country, opponents decry road pricing as elitist, unfair to poor and middle income, and likely to deepen social divisions. Who wins and who loses from pricing schemes depend on exactly which road facilities are tolled, how those tolls vary by time of day, and what happens to the revenues. Pricing Roads, Advancing Equity, a recent report by TransForm and the Natural Resources Defense Council, shows how pricing policy could help build a more just society by improving mobility options for those historically ill-served by existing transportation systems. A well-conceived and -implemented pricing plan will result in a transportation system that’s faster and fairer.

The case for congestion pricing strengthens in a future with electric and autonomous vehicles. The gas tax doesn’t generate enough revenue to preserve the road investments we’ve already made, and with increased electrification the road financing problem gets worse. The Puget Sound region’s long-term financial plan already includes mileage-based road fees because no other funding mechanism is likely to work. When autonomous vehicles arrive, Cascadia’s congestion problem could get worse. If commuters can nap while commuting in their own car, they may tolerate much more time in the car. Without a price signal to allocate valuable road space, the robots will further crowd our streets and highways.

Pricing roads makes sense today and is essential to our transportation future. Knowing that there is a large hill to climb to win public support means advocates for pricing must present compelling information about how different groups will come out ahead. Better models of a future with pricing and well-designed pilot programs could help Seattle and other cities in Cascadia enjoy the benefits of a more equitable, more efficient, less congested, and less polluting transportation system.