My son will be two and a half in a couple of weeks, so our family spends a lot of time trying to protect him from things: stepping in front of a car, swallowing a screw, licking an electrical socket.

Then there have been the harder things: protecting him from sleeplessness by letting him learn to soothe himself. Protecting him from recklessness by letting him fall off things that are a little unstable. Stepping back so he can learn when he needs to care for himself.

There’s a new genre of how-to parenting articles called “how to talk to your kids about climate change.” My now-colleague Anna happened to publish one just after my son was born.

Now that Barney and I can talk, I think about this future conversation quite a bit. For some reason it popped into my head while we were roughhousing in his bed on Saturday, hiding beneath his blankets with stuffed animals. It made me sit still for a moment while he growled and giggled.

I realized how fragile and temporary his ignorance about his future is. I wanted to protect it, because I wanted it to protect him.

How am I going to explain to him that he’s likely to see the submersion of Miami and the forced abandonment of Bangladesh by tens of millions of people? That Europe’s refugee “crisis” of the last few years, the one that canny thugs have already exploited to win power in Hungary, Italy and elsewhere, is just a shadow of the migrant crises to come? That his hometown might never see another summer without wildfire smoke that reddens the sun and forces the young, old and sick to hide indoors for days?

That if we keep pumping coal soot and fracked gas into the sky, the increased air pollution alone will kill at least as many people as 25 Holocausts?

How am I going to explain to him that we saw this coming the whole time?

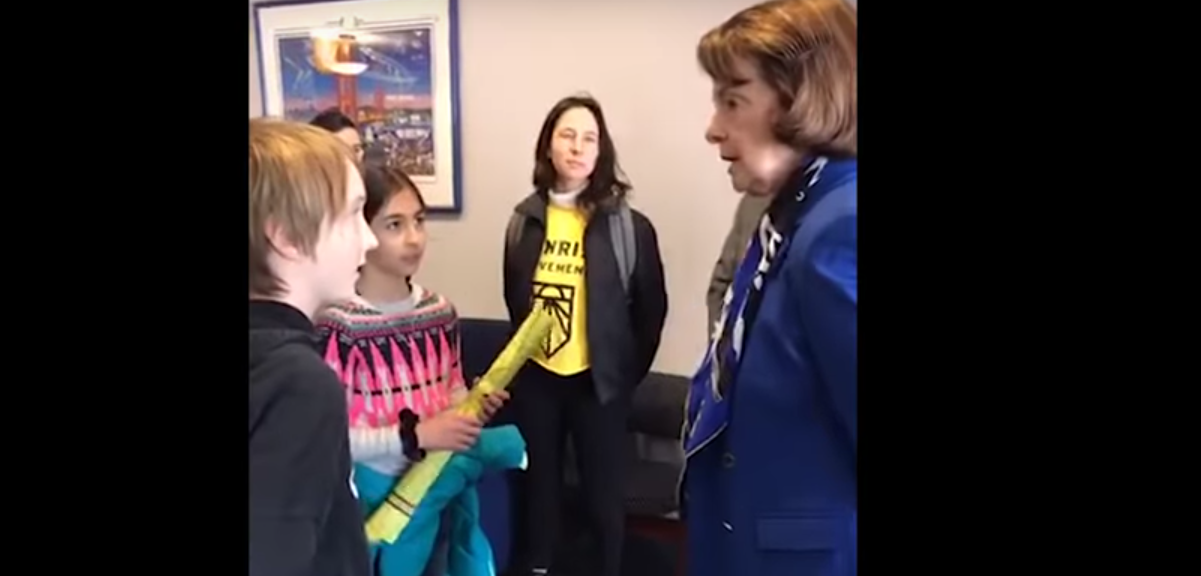

The heart-slicing edge of last weekend’s viral video of US Sen. Dianne Feinstein of California facing down a group of children over climate action wasn’t the 85-year-old senator’s weary, patronizing explanation that she was doing her best. It was the nervous little intakes of breath between the girls’ and boys’ words, earnestly believing that if they speak, the people in their government might listen, and that if we act, the people in other governments might, too.

Well, thanks to the video, today more people are listening, at least a little bit. They were forced to, because those intakes of breath cut so many of us so deeply.

This generation, including my son, still has time to take that breath—to believe. Our grandchildren, coming of age in a world increasingly scarred by today’s inaction, might not have that chance. Their faith in collective action might have been scratched out.

We talk a lot about those scars we’re carving into our planet, but I don’t think we talk much about how the effects of climate change could damage our souls. Physical scars have a way of becoming mental ones.

When I try to think about how this could play out, I think about 15 generations of American toddlers, black and white and brown, growing up under chattel slavery. I imagine their slowly dawning comprehensions of how their society worked and the cognitive dissonance of watching their peers—still children—slowly separate into enslavers and enslaved. I imagine the terrible botany of private rationalizations that transformed the physical fact of slavery in those years into America’s ageless, unkillable kudzu of racism.

I can imagine a similar dissonance, and a similar risk of multigenerational cultural rot, in the minds and hearts of our descendants as the residents of a decreasingly habitable planet struggle to live in peace. I sometimes wonder if my son will someday see the airplane that took me to my honeymoon, or the one I’ll be taking to my college reunion in May, as the moral equivalent of a slave ship, making an unfathomable number of future lives worse for the sake of my material comfort. And I wonder if my hope should be that he won’t see me that way, or that he’ll still have the moral ability to.

I’ll savor my son’s ignorance right now. But in the longer run, I can’t afford to protect it. None of us can. The way to protect our children from climate change is to let them know exactly what their future currently looks like, and what we can do now to change it.

And then, of course, we have to listen to what they say in response. And we have to act, using the power they lack.

“The job of older people, at this late date, is to have the backs of the young,” Bill McKibben, 58, wrote on Saturday.

That’s just another way of saying that we humans need this generation of children, born in time to see the world of their ancestors. And if you’re one of them—when you’re one of them, Barney—your job is going to be to use your precious breath as well as you can, too.