One of North America’s biggest new ideas for greener transportation is spreading north.

A year after a pair of California state senators drew national attention with a proposal to lift apartment bans from all residential land within a quarter mile of frequent transit, Oregon has a similar bill of its own.

Senate Bill 10, which was introduced last week, had its first public hearing Monday, February 25.

This isn’t the first time the idea of state-led housing legalization, focused specifically around transit, has come to Cascadia. But it’s definitely one of the most ambitious.

SB 10 is barely over one page long, but it’s quite a bill. It would legalize hundreds of thousands of potential future homes, almost all of them in three urban areas: Portland, Eugene-Springfield, and Salem. The buildings it’d legalize—though not, of course, guarantee would or could be built—range from two-story townhomes in small cities to 6-story apartment blocks near Portland-area light rail stops.

Also, for all projects less than half a mile from rail or other frequent transit, the bill would strike down all mandatory parking quotas.

There’s compelling logic to it. Oregonians have spent billions of dollars on their mass transit systems and spend more than a billion more every year. Why not let people live near them if they want to?

Similarly, what better place to allow new below-market housing intended to serve Oregonians who are particularly unlikely to own cars?

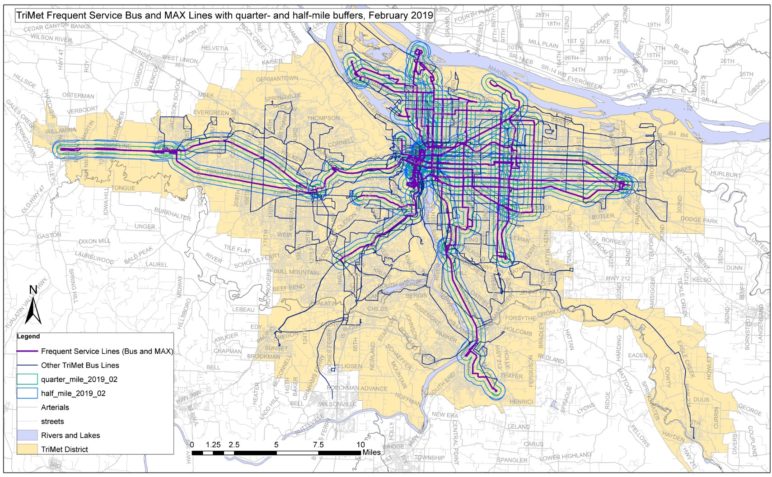

Greater Portland’s regional transit agency TriMet has mapped the land in the Portland area where zoning would be somehow affected:

But what sort of housing, exactly, would the bill legalize?

SB 10 isn’t clear on the technical but important question of whether its new density limits refer to net or gross acreage—that is, whether undevelopable land like streets is included in the ratios. And the office of Sen. Peter Courtney, who sponsored the bill, didn’t respond on the record to a request for clarification last week. But because of the way the regulation is written—applying at the lot level rather than setting average density throughout an area—the intent is probably to refer to net density.

Below are a series of slides, created by Seattle-based urban design firm GGLO Design unless noted, showing roughly what scale of housing the bill would allow where. (Thanks to my colleague Dan Bertolet for compiling all the images below for a 2009 post on his personal blog, before his current stint at Sightline.)

Keep in mind that the law would apply equally to public and private projects, market-rate and below-market homes.

In Portland-area cities above 10,000 residents

(Here’s a list of Oregon cities by population.)

Within a quarter-mile of a light rail station: 140 homes per acre. So, somewhat less than the building below, which has 162 homes per net acre.

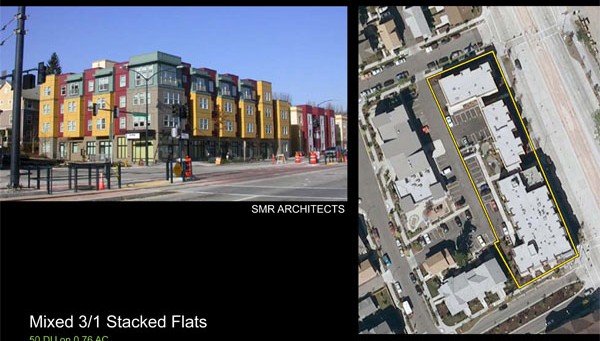

Within a quarter-mile of any passenger rail or bus rapid transit line (even without a current station) or a frequent bus line (buses every 15 minutes or better during peak hours): 75 homes per acre. So, a bit more than the building below, which has 66 homes per acre.

Between one-quarter and one-half mile of rail, BRT or a frequent bus: 45 homes per acre. So, a bit denser than this, which has 41 homes per acre:

In cities above 10,000 residents in one of Oregon’s seven metropolitan planning organizations

(Here’s a site that gives a list of Oregon’s seven MPOs. It’s basically the 10 biggest urban clusters, including some suburbs of Longview-Kelso and Walla Walla, Wash. Here’s a list of Oregon cities by population.)

Within a quarter-mile of any passenger rail or bus rapid transit line (even without a nearby station) or a frequent bus line (buses every 15 minutes or better during peak hours): 50 homes per acre. So, somewhat denser than the below (which you’ll notice is also the closest example for the scenario immediately above), which has 41 homes per acre:

Between one-quarter and one-half mile of rail, BRT or a frequent bus: 25 homes per acre. So, about the same as this fiveplex, which offers 27 homes per acre:

In cities above 10,000 residents that aren’t in one of Oregon’s seven mpos

At the moment, there don’t seem to be an such cities in Oregon, unless one such as, say, Woodburn were to sharply increase its peak-hour transit frequency. So the below images seem to be theoretical, for now.

Within a quarter-mile of any passenger rail or bus rapid transit line (even without a nearby station) or a frequent bus line (buses every 15 minutes or better during peak hours): 25 homes per acre. Again, that’s about the same as this fiveplex, which offers 27 homes per acre:

Between one-quarter and one-half mile of rail, BRT or a frequent bus: 14 homes per acre. That’s exactly the density of these two-story townhomes:

Again: Senate Bill 10 wouldn’t require any building to be replaced. It wouldn’t guarantee that it would be profitable for anyone to actually build anything pictured above. But it would make it possible for buildings like the above to exist. Today, in many areas, that’s illegal.

“Smart growth” like this would sharply reduce energy bills, infrastructure expenses and sprawl

If this bill passes, and if buildings like these are eventually built, what would the effects be?

A report released last year by the new national organization Up For Growth, Housing Underproduction in Oregon, offers a partial answer. It estimated that in the wake of the Great Recession’s collapse in homebuilding, Oregon is 155,000 homes short of its long-term needs. The report (authored by economic consulting firm ECONorthwest) then floated two scenarios for building new homes:

- A “more of the same” scenario that assumed Oregon would continue building detached homes, low-rise attached homes and towers at the same ratios as its past;

- A “smart growth” scenario that assumed Oregon would concentrate new homes near jobs and transit, as envisioned by Senate Bill 10.

According to ECONorthwest’s calculations, the “smart growth” scenario would (compared with “more of the same”) reduce the rate of sprawl by 81 percent; reduce auto miles traveled by 34 percent; and reduce public infrastructure spending by 89 percent.

Building many more homes near transit would save money. It would help preserve the global and local ecosystem. It would, in combination with necessary public support for lower-income Oregonians, help keep everyone housed who needs to be.

Should what’s good also be legal? That’s the question SB 10 asks of us.

Comments are closed.