Methane gas, commonly referred to as “natural gas,” is the fossil fuel with the most positive image. Natural gas is marketed as not just cleaner than other fossil fuels, but as “clean”—a demonstrably false descriptor with an endless number of caveats. Oil and gas companies promote gas subsidiaries by prominently featuring the word “clean” in the company’s name or marketing and suggest we pair natural gas with renewable energy as a solution to our greenhouse gas problems. This dubious pairing has found its way into decarbonization policy at both the state and federal level.

The oil and gas industry’s greenwashing campaign for methane gas began decades ago when it rebranded the product as “natural gas”—a hugely successful strategy. Studies show that the average American believes natural gas to be a clean fuel that does little harm from a climate or pollution perspective. Natural gas proponents point out that gas produces less carbon emissions than coal or oil at the point of combustion. That’s an accurate statement. At the point of combustion, natural gas has a smaller carbon footprint than other fossil fuels, and it can yield as much energy as coal with roughly half the carbon emissions. The reduction of carbon dioxide—the most prevalent greenhouse gas in the atmosphere—is a goal around which most climate policy is focused. Measured per unit of energy produced, natural gas combustion also emits fewer air pollutants including carbon dioxide, small particulate matter, nitrous oxide, and sulfur dioxide. Some of these pollutants, like diesel particulate matter, pose serious health risks.

But the point of combustion is just one stage in the life-cycle of natural gas. There’s a reason the industry deliberately ignores the remainder of emissions produced by natural gas: there is strong evidence that when the full life cycle is taken into account, natural gas can produce the same amount or more greenhouse gas emissions as other fossil fuels. The problem with gas—and it’s a big one—is that it contributes to global warming before ever reaching the point of combustion. Transporting and processing natural gas leaks methane, a much more potent greenhouse gas, directly into the atmosphere. Methane makes up 85 to 95 percent of the natural gas customers receive, and it is 34 to 87 times more potent than carbon dioxide when it comes to trapping heat in the atmosphere.

“When the full life cycle is taken into account, natural gas can produce the same amount or more greenhouse gas emissions as other fossil fuels.”

From the drilling site to the consumer, methane easily escapes into the atmosphere at various points along the supply chain. The release of methane gas offsets the climate benefits at the point of combustion. Methane leaks from fossil fuel infrastructure take two forms: fugitive emissions and venting. “Fugitive emissions” are unintentional leaks from gas distribution infrastructure such as drilling sites, pipelines, and compressor stations. Aging natural gas infrastructure in the US is spewing untold amounts of methane directly into the atmosphere on a daily basis. “Venting” is the intentional release of methane, which happens all along the supply chain—from drilling sites to gas processing and storage sites such as LNG facilities.1

All told, drillers on federal lands alone released enough gas into the atmosphere between 2009 and 2014 to power 5.1 million homes for a full year. Several high profile incidents, including the disastrous 2016 Aliso Canyon gas leak in California, are merely the tip of a proverbial iceberg containing millions of ongoing leaks and intentional methane releases. Over the past decade, widespread observations of high methane emissions have not only called into question whether we are getting the facts right on natural gas but strongly suggested that we are not.

Methane leakage is an oft-ignored pathway to global warming and the nexus of debate over the true climate impacts of gas. Understanding and engaging in this debate is vital before we expand natural gas infrastructure in the Pacific Northwest. Focusing only on the point of combustion produces confusion and misinformation about natural gas’s ability to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, or serve as a “bridge fuel” to renewable sources of energy.2 Then there’s the confusing terminology, unsettled and emerging science, and deliberate misrepresentations by the gas industry. The result is an alarming lack of awareness when it comes to the true climate implications of natural gas. People who in good faith believe that natural gas is a cleaner alternative have been deceived for decades.

It’s time for a reality check: When researchers examine the full impact of natural gas, many conclude that it is not substantially better for the climate than coal. In fact, under some circumstances, it may even be worse.

The purpose of this series is to demystify the “natural” gas debate.

- Methane traps more heat per pound than carbon dioxide but has a shorter atmospheric lifespan. Policy decisions should look at impacts over multiple time frames.

- The climate benefits of switching to natural gas vary depending on the fuel it is replacing, and it has a break-even point with any “dirtier” fuel. Methane leakage rates must be kept low to avoid breaking even or to justify the significant investments of infrastructure conversion.

- US methane emissions are increasing just as natural gas production is increasing. While there is still debate over the fossil fuel industry’s precise contribution to the increase, we have enough information to take action. Indeed, taking action is the only way we’ll clarify the debate.

- There is widespread agreement that we are underestimating methane emissions and need to strengthen our data through better industry oversight.

- The supposed benefits only consider emissions reductions at the point of combustion, omitting the full picture of natural gas’ greenhouse impact.

These five key facts should inform Northwest policy decisions about natural facilities claiming to be “clean.”

Why you should care about the natural gas problem

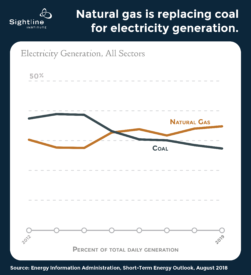

The stakes could hardly be higher. Nationwide in the United States, natural gas extraction and burning are increasing dramatically. The US fracking boom has produced surplus gas supplies and lowered prices. Gas-fired power plants produced 34 percent of US electricity in 2016, up from 22 percent in 2007. In fact, 2016 marked the first year that natural gas was the leading fuel source for US power generation, and it is expected to maintain the largest share of the electricity mix through at least 2040.

Original Sightline Institute graphic, available under our free use policy.

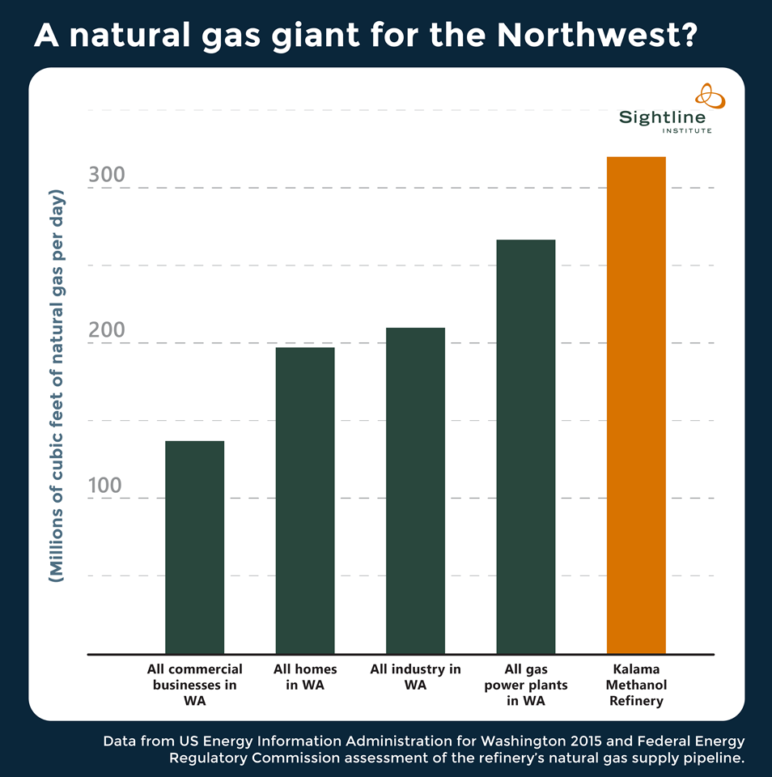

In regions like the Pacific Northwest, a range of gas export proposals would further ramp-up fracking, gas consumption, and methane leakage. Just one of these projects, a gas-to-methanol refinery slated for development at Kalama, Washington, would consume more gas than the amount burned by every gas-fired power plant in the state.

Original Sightline Institute graphic, available under our free use policy.

The Kalama project, while very large, is not unique. A companion methanol proposal near Clatskanie, Oregon, is just as big. Fossil fuel companies around the Northwest are aiming to build new, large-scale, gas-consuming infrastructure. Over the last few years the Northwest has been confronted with new gas development projects that would consume roughly two billion cubic feet per day. This staggering figure exceeds the total current usage of Idaho, Oregon, and Washington combined. Two such projects are liquefied natural gas (LNG) facilities in Tacoma, Washington, and Coos Bay, Oregon. Meanwhile, the Canadian government has granted export licenses for more than a dozen LNG export projects along the British Columbia coast.

The backers of these projects have marketed their gas expansion plans as environmentally beneficial. The claims are often dubious. While natural gas could have some benefits—replacing existing coal-fired power plants, for example—the rapid expansion of natural gas infrastructure for every other imaginable use will lock the region into the fuel’s detriments. Modern science indicates that if natural gas can still be used as a bridge fuel, and that’s a big “if,” it’s a bridge that must be traversed with a caution the gas industry has proved unwilling or unable to practice.

High Momentum, High Risk

In the 1970s, the world experienced an energy crisis. Natural gas hit a market peak in the US, and this decade saw the birth of the concept that natural gas could be used as a “bridge fuel” between fossil fuels and renewable energy. Of the three major fossil fuels, methane has the lowest amount of carbon per unit of energy. The bridge fuel concept did not catch on until decades later but it has more momentum than ever, just when both the natural gas industry and our knowledge of its effect on the environment have drastically changed. Now that we are 40 years past the introduction of the “bridge fuel” concept and need to take urgent action on climate change, many scientists warn that we have passed the timeframe in which natural gas could be used as a bridge without worsening climate change.

That’s not all that’s changed. Up until the last decade, natural gas was derived through conventional extraction—in simplified terms, drillers installed piping systems into underground gas basins and gas readily flowed out. Conventional extraction didn’t put much demand on water resources, especially when compared with other fossil fuels. That made it appealing from both a pollution and water consumption perspective. Today, though, two-thirds (67 percent) of the natural gas produced in the United States comes from a harmful and toxic process known as fracking.

Fracking targets geologic formations that contain fossil fuels that are not so easily extracted, primarily tight sands and organic-rich shales. Companies that engage in fracking inject large quantities of water, sand and chemicals—two billion gallons of chemicals between 2005 and 2013—into a fossil fuel well at high pressure. The pressure fractures the earth inside the gas well, releasing larger quantities of gas or oil.

By 2010, natural gas producers were fracking more than 90 percent of the natural gas wells in the United States. The gas fracking boom led to a surplus gas supply and created a drive for the industry to convince domestic and international customers to buy more gas. In turn, more infrastructure must get built to deliver the surplus gas to customers. The possible result of this build-out makes it likely that states and regions will get locked into reliance on fracked gas for the foreseeable future. This would make fracked gas less of a bridge and more of a destination.

Fracking contributed to a dramatic increase in US natural gas production, multiplying the once less-alarming issues related to natural gas. The fracking boom has produced major environmental risks, including lowered freshwater supply and the generation of millions of gallons of toxic and high-salinity fracking wastewater. Fracking poses a greater risk to air and water quality than conventional extraction, and increased fracked gas production leaks more heat-trapping methane into the atmosphere.

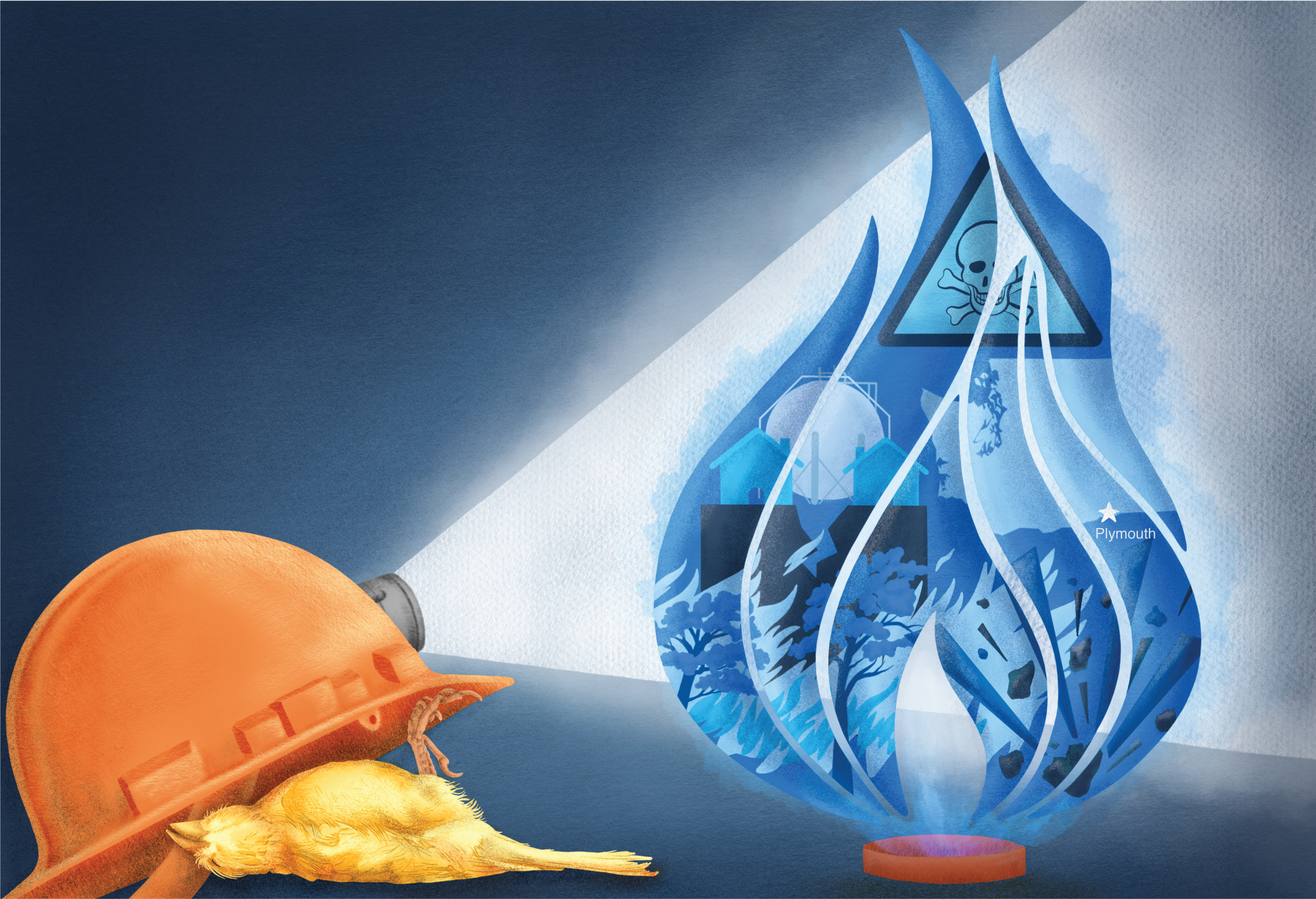

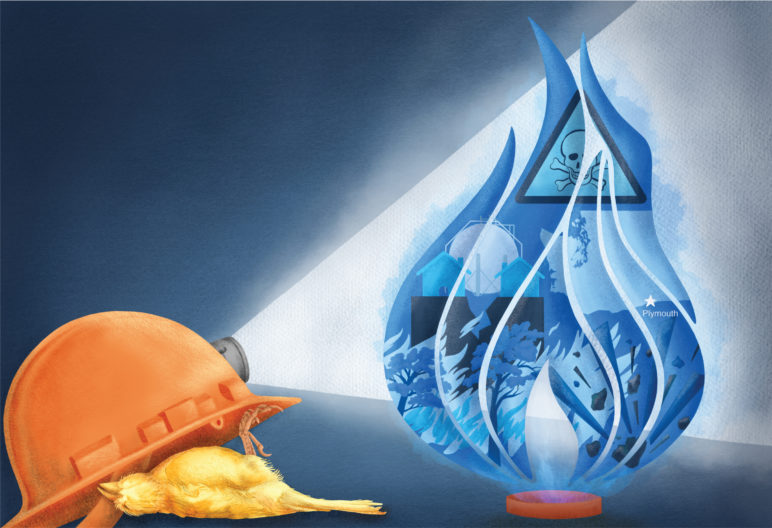

Natural gas has changed and so too should our analysis of it. The perils of fracking and the ongoing expansion of scientific knowledge about methane make it clear that if natural gas is to be used as a bridge fuel, the bridge must be traversed carefully. Unfortunately, Northwest policymakers are not traversing the bridge carefully, but rather rushing across it. In recent years there have been three proposals to turn Washington and Oregon into methanol surrogates for China, to the detriment of three Washington cities and their water resources. The misconceptions around natural gas allowed the methanol project’s backers to sweet talk misinformed officials at multiple levels of state and local government.

The success of decades of greenwashing natural gas—now fracked gas—threatens to put Northwest climate goals at risk.

Thanks to Adrian Down and Marcia Baker, who contributed research to this series.

This is part of a trilogy of articles to provide depth and context to methane leaks. Read the other pieces in this series:

Footnotes:

1. Venting methane is also common practice at oil wells and coal basins during the process of extraction.↩

2. The “bridge fuel” concept was first floated in the 1970s when the public knew less about the harms of methane. It proposed that we use natural gas as a transitional fuel between carbon-intensive fuels like oil and gas and renewable energy.↩

Robert Baker

Shouldn’t the bar graph titled “A natural gas giant for the Northwest?” be sub-titled “Natural gas consumed daily” rather than “Natural gas produced daily”?

Tarika Powell

Hi Robert, you are absolutely correct that it should’ve said “consumed” rather than “produced.” This has been fixed, thanks so much!

kristen pezda

I applaud that this article looks at the lifecycle perspective of energy sourcing. What is your opinion on sourcing methane from existing waste emissions? Currently, 80% of methane emissions come from agriculture and human waste, and gas companies are quickly trying to switch to using this methane (instead of letting it go into the air, like it currently does) instead of fracked methane. From a lifecycle perspective, this eliminates upstream methane emissions, and actually is a carbon negative lifecycle loop. The only thing preventing companies from rapidly expanding this technology themselves (they currently rely on private companies/developers to start these projects), is existing state law that prohibits them from selling anything other than fracked gas. Would like to see an analysis on this if you’re interested.

Tarika Powell

Hi Kristin, thank you for your question! A lot of people are wondering about the potential of capturing landfill gas or agricultural methane, since it could really reduce the amount of methane entering the atmosphere. I’m cautious about the point where we go from idea to execution, which is where humans usually mess things up, right? I have a lot of thoughts about it but I’ll try to be brief and give my general opinion.

We’re out of alignment on the topic of landfill/agricultural methane for a couple reasons.

1. It’s being labeled “renewable gas.” This is incredibly misleading, and by incredibly misleading I mean, “Are they seriously just going to tell a bold-faced lie through naming… again?!” I talk in this piece about how the term “natural gas” misleads people just based on the name, which was an intentional marketing choice by the fossil fuel industry. The result is that people widely believe natural gas is something that it is not. I’m concerned about making the same mistake with “renewable” gas. There’s nothing renewable about it. In the energy sector, we should not just casually use the word “renewable” for non-renewables. Words mean things.

2. The infrastructure that would capture and transport landfill/agricultural gas would be susceptible to the same fugitive emissions problems discussed in the article. We have to fix those issues in the gas industry no matter the source of the gas.

3. People have an overly rosy idea of how much of the gas would actually be captured. I think in some people’s brains (not yours) this solution looks like a big vacuum cleaner that sucks up all the methane and that’s not how it works.

So, while there could be some benefits, the problem is that we always rush into things as if they are total solutions rather than narrow solutions to particular problems. I’m a little unnerved when I see starry eyes on this topic, because I’m not seeing plans to have a different gas industry, just an additional source for gas. I feel that it’s an idea that should be approached with the concurrent intent of reducing fugitive emissions in infrastructure. If we don’t do that, we won’t even be capturing nearly as much methane as we tell ourselves.

I’d also like to quickly ask about your 80% figure; I don’t think it’s correct but I’m aware that you may be referring to global emissions while this article focuses on US emissions. As far as global emissions, natural sources of methane (like wetlands) account for roughly 20% and fossil fuels roughly another 20%, leaving about 60% for all other sources rather than 80%. Even only looking at anthropomorphic (man-made) emissions, the US EPA analysis linked to in Part 3 of this series puts the fossil fuel industry’s contribution to methane emissions at nearly 40% while landfills, agriculture, and manure management make up about 50%.

This is still a very significant number that you are right, we need to address. But not in a way that repeats the exact same mistakes.

Thanks again for your question! This is a very interesting topic.

Balter

It seems highly unlikely an increase from 0.03% to 0.04% atmospheric carbon dioxide since the end of the Little Ice Age is significant.

Steven Storms

I want to thank Sightline and Tarika for continually for shedding such clear and understandable information. It is so important that the public gets such good information to counteract the greenwashing that is continually spewed by the fossil fuel industry. They spend millions in advertising in order to protect their industry at all cost. Your voice is needed and appreciated. Thanks. Steven Storms

Ken Chawkins

Respect the article and understand the intent. Interesting that you are claiming that the industry is using “labeling” as a way to move their interests and you’re worried that labeling anthropomorphic sources as “renewable” would be equally so. I would submit that using phrases like “greenwashing” are equally misleading. There are very well established academic resources that DO see methane as Natural Gas…and see Renewable natural gas as renewable. From my perspective – full disclosure that I worked in the electric industry for almost 20 years and am now in the gas industry – unless/until we find a way to reduce the amount of methane that goes to atmosphere every day from the human waste stream and agricultural activity, it will renew itself every single day…like the sun rising and the wind blowing. Ground extraction of fossil fuels does NOT renew itself. When they’re done with a well, they’re done. I agree wholeheartedly with your comment about reducing fugitive emissions…tightening the system and getting rid of bad actors who extract carelessly is critical to this effort. Let’s tighten things, pull more renewable NG from the air (going to atmosphere otherwise), pull less from the ground and use the existing infrastructure to keep costs down. It is but ONE tool in the box – along with wind, solar, hydro, etc… – as part of an “all of the above” approach to getting where we need to go faster, safer and cheaper. (By the way…the 80% number is for CA. Methane makes up about 10% of our GHGs. Of that 10%, 80+% comes from Ag/Human waste stream. That number is different state by state.)

Tarika Powell

Thanks very much for your comment, Mr. Chawkins. I actually love talking about this issue with people who work in the industry because, as you can imagine, I don’t find many interested parties at parties.

The rational is certainly an interesting argument: we keep producing trash and eating lots of cows, we’re going to keep producing lots of trash and eating lots of cows, so technically we can look at it as a resource that renews. Now, you and I know that we’re not talking about renewable resources as a layperson understands the term, but we also know that laypeople will not have the same background knowledge as you and I. They will hear “renewable gas” and think of the same clean & wonderful things they’ve always thought of when you say “renewables,” and that is very problematic when we’re actually talking about gigantic piles of trash. In my opinion the term will only further allow gas to be paired with renewables as a “clean fuel” when it is not, so it benefits no one but project proponents and the gas industry to call it that.

When you get into making policy decisions, they heavily involve the conceptions & misconceptions of the general public. I believe very strongly that individuals and communities can make great governing decisions when they have accurate information. As a former educator, I’m an endless proponent of the power of knowledge, facts, and discernment. Everything would be great if everyone was a lifelong learner who was constantly challenging their own assumptions and biases. I also know that realistically people do not have time to look everything up, nor an inherent psychological driver to challenge their own firmly held beliefs. In fact we have the opposite, a psychological drive to protect our own firmly held beliefs, even when they aren’t based in fact. (My favorite discussion of this is actually in a comic, because I’m a serious intellectual.) As smart as we are, we resist changes to what we think we know no matter how we came to believe that thing. So I feel that misleading terms do a disservice to people who are trying to make the best decisions – it gives them incorrect information to go on. Great marketing, like what the industry can afford, also ties that incorrect information to emotional foundations, making it even harder to dislodge misconceptions.

Long story short, people make assumptions based on what things are called and they can hold those assumptions very strongly – ask anyone in marketing or messaging. I think our society can make much more progress when we can start with the facts instead of creating and then correcting misconceptions. I think we can make much more progress, and faster, if we tell people the truth and part of that to me is calling things what they are. But my opinions on that come from being an educator as much as they come from being a fossil fuel researcher.

Like I said I find the argument for calling it “renewable gas” interesting on a purely intellectual level. It’s simultaneously a fascinating technicality and a sad commentary on how we’ve come to accept all the man-made waste we put into the world. But since I’m constantly working with communities who are truly trying to understand these issues, and since I want everyone to have fewer misconceptions, on a practical level I am completely opposed to the terminology. I’m not opposed to the idea – it’s a great idea. But I’m opposed to calling it that.

Thanks so much for sharing your perspective and thanks for clarifying that the 80% is about CA.

Diana

Well written and informative and educational piece of writing and research. Thank you!

Nick

Please provide a source that the industry has gone through “rebranding” efforts to change methane into natural gas. From the best I could research, natural gas has been the common term for more than a century. It has been used since at least the 1890’s making its way into a Supreme Court decision: United States v. Buffalo Natural Gas Fuel Co. By 1938 the term was so commonly understood that the Natural Gas Act did not even include methane or further clarification in the definition.

I think you missed a key point when you said that natural gas had only half the carbon intensity of coal. While it’s true that it’s roughly a factor of 2x different in kg/BTU (as linked to EIA), the key issue is kg/MWh. Old coal plants currently in operation have average thermal efficiencies in the 30’s and sometimes the low 40’s. However, combined cycle natural gas power plants are all in the high 50’s with records being set above 60% thermal efficiency. This additional 1.5x gain puts new natural gas closer to 1/3 the carbon intensity as our current coal fleet.

You also didn’t cover the primary reason that natural gas is viewed as a bridge fuel. Combined cycle natural gas plants have far more operational flexibility than old style steam generators. Old steam generators were designed and generally constrained to operating in a baseload mode. A power plant that has limited ability to operate as a load follower or peaking power plant can not integrate intermittent resources such as wind and solar. This is the biggest operational challenge to places like CA with high solar penetration. Solar generation drops off quickly even as residential demand begins to climb in the evening. This means the rest of the grid must change it’s power output quite rapidly. Without the ability to respond, you can’t integrate more renewables. By swapping old coal and natural gas boilers for newer combined cycle plants we’ve allowed far more wind and solar to be added to the grid.

We live in a capital constrained world and as such we must mitigate the most CO2 per dollar. It should not be accepted prima facie that new natural gas plants are bad in all situations. In a coal heavy ISO/RTO like the southeast and midwest, adding a new natural gas plant and far more wind and solar may reduce more carbon than wind, solar and storage for the same cost. A careful engineering analysis and modeling is required. We can’t afford to be wasteful or careless when the problem is so big, costly and urgent.

Steve

The failure to actually state and compare the whole lifecycle emissions of natural gas per kw/h vs other fuel types is a major failure of this article. Im actually exasperated you managed to write this much supposition without clearly stating it.

Romolo

Hi Tarika

Congrats for your very detailed publication. Is all true.

I would like to read this one that an Australian journalist Nicki Bourlioufas who wrote for our technology on Yahoo.com.au.

Please have a look and feel free to contact me directly.

https://www.annscaprospecting.com/company-invents-tech-to-change-gas-mining-forever/

Regards

R.Bertani

Romolo

Hi Tarika

I wrote a comment before but I cant find it here.

was deleted from the site or I accidentally make something wrong?

Romolo Bertani

Kelsey Hamlin

Romolo, it wasn’t deleted! We just hadn’t approved it yet; thanks for asking! And sorry for the wait. – Sightline’s communications associate, Kelsey Hamlin

Paul Thiers

Thank you for this valuable set of articles, Ms. Powell. It is a real contribution.

I also saw your sound comments above regarding anaerobic digestion of animal/municipal waste. I have studied animal waste to energy projects on concentrated animal feeding operations (CAFOS) in China for some years. I think the key is to view this as a waste management policy, not as climate change or even energy policy. The net reduction in GHG emissions is minimal but the benefits to local water pollution is substantial. And the energy production (best done on site by immediately generating electricity) can help provide financial incentive. Until we can eliminate CAFOs altogether, waste to energy is a good harm reduction technology. But, like the biofuel craze a few years ago, it can only be sold a as climate positive with heroic modeling assumptions. Waste management is a good thing but it is not renewable energy.

Paul Thiers

Washington State University Vancouver

april keating

I would like to invite folks to come on a tour of gas infrastructure in a rural community in northern WV. Contact me at protect@mlpawv.com or look for Mountain Lakes Preservation Alliance on facebook and look for our Toxic Tour.

Balter

Of course methanol was an initiative of the green movement in the first place: touted as “biofuel” this scheme to turn food into fuel was amped up by President Obama to where the increase in food prices caused worldwide political unrest.

Kelsey Hamlin

Methane (methanol is the liquid, not the gas) that comes from food or waste still has the lethal heating structure, but it isn’t derived from fracking unlike natural gas. – Kelsey Hamlin, Sightline Communications Associate

Robert

Hi, there. Thank you for your thoughtful article.

At the top, you say “The oil and gas industry’s greenwashing campaign for methane gas began decades ago when it rebranded the product as “natural gas”—a hugely successful strategy.” However, “natural gas” is a term used at least as far back as the early 19th century. It is not a re-branding.

I wish you wouldn’t include ridiculous claims like these. It makes it easier for opponents to dismiss concerns like ours.

Shaun P Murphy

– keep up the good work. there is so much LACK of education and hoodwinking of the public that makes for such an uphill battle to have more people understand the reality of the fossil fuel industry.