An earlier version of this project was published in March by the Portland Tribune and KGW as part of the Open:Housing journalism collaborative.

Everybody in the real estate business wants a piece of Robert Cheney.

The recent Portland State University master’s grad and his girlfriend are fairly typical of the Pacific Northwest’s 2.2 million tenant households, looking for a fair deal in their price range. But Cheney and his girlfriend are unusual in one way: Their apartment, unlike 94 percent of Cascadia’s rental housing stock, was constructed after 2010.

“We’re pretty stoked that it’s a modern building, and it’s probably not going to collapse tomorrow in the earthquake,” said Cheney, while carrying a takeout dinner into his Northwest Portland apartment building, the Cordelia Apartments, on a Friday evening last summer.

If the cities of the Northwest want to keep building enough homes to keep up with long-term growth, people like Cheney and his girlfriend are the ones who’ll end up signing the checks.

It’s their rent payments, and the promise of more for decades to come, that finance every swing of every hammer at every apartment site across the region.

Their rent also pays the window-washing bill of the bank that issued the building’s construction loan. It buys the paper clips on the desks of the architecture firm that designed the building and covers the car payments of the real estate developer. Their rent lays the water main that feeds their shower and the sewers that snake beneath it. It funds the summer vacation of the person who used to own the land beneath their building and, through property taxes, it puts food in the cafeteria of the county jail.

All of this gets paid for, ultimately, out of the cash that Cheney and his girlfriend fork over each month for the key to their 723-square-foot apartment.

But who gets how much of that rent check?

As rents across the Northwest have soared over the last decade in buildings new and old, the answer to that simple, mysterious question—where exactly does rent money go?—may also be the way to start answering another question: What, if anything, could governments do to make those rent checks smaller?

I don’t mean the short-term price dip Portland’s higher-end renters are currently enjoying thanks to the city’s first apartment glut in twelve years. I was interested in what it’d take to get a permanent drop in the market price of newly built homes.

So I decided to look into it.

Starting with the basic specs of a newish building like Cheney’s—135 homes on five stories atop 30,600 square feet of Northwest Portland dirt—I walked through every step of what it took to build the apartments hitting the market today, checking with multiple experts for estimates of what each line item costs.

One note: Because apartment buildings take a few years to build, the ones opening for rental right now were approved before Portland started requiring a share of homes in all larger buildings to be set aside for lower-income families at below-market rates. This project focuses on buildings available for rent right now, so the numbers below don’t reflect that program.

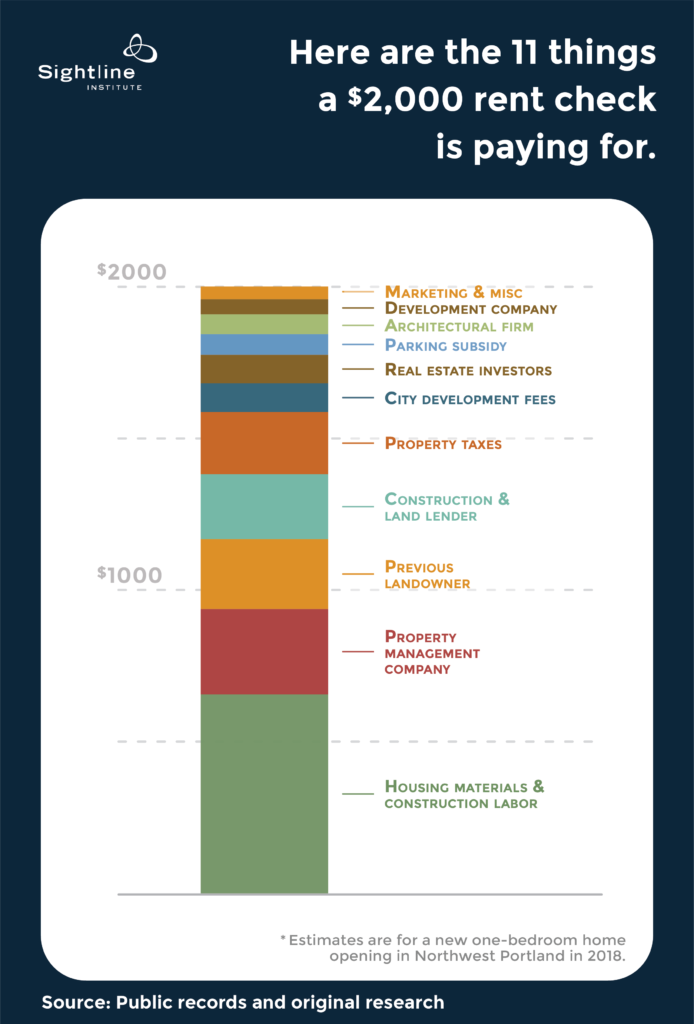

The chart below shows the results: a breakdown of the 11 main factors that drive the price of rent for someone like Cheney living in a market-rate apartment in Portland.

Then I went through the whole process a second time, asking a new question at each step: Is there some way to make that cheaper? And if there were a way, how much could it potentially save someone like Cheney every month?

Both costs and rents have been scaled to fit a $2,000 monthly apartment. (Robert Cheney’s actual rent was less than $2,000, in part because his building is a few years old.) Here’s the spreadsheet I used.

Original Sightline Institute graphic, available under our free use policy.

Title, marketing & miscellaneous: $41/month (2 percent)

These folks negotiate the land purchase and get the building in front of tenants.

Development company: $50/month (3 percent)

Asked how much of his rent ends up in the developer’s pocket, Robert Cheney guessed 40 percent. Nope. Unless the developers are also their own real estate investors (in which case, see below) his or her salary and business expenses come to about 3 percent of the final rent payments.

Architectural firm: $65/month (3 percent)

A full-service architectural firm might charge 8 percent of construction costs to do design, planning and legal work. It comes to about 3 percent of a rent check.

Parking subsidy: $68/month (3 percent)

This isn’t the amount you’d have to pay for a parking space in a building like this; that’d be another $175 on top of the $2,000 rent. No, this is the cost of building the parking garage that isn’t covered by that $175 per stall. It gets paid out of everyone’s rent whether they have a car or not.

If the building were to offer “free” parking for every home, this number would need to be $175 higher—and so would the total rent.

Short-term real estate investors: $94/month (5 percent)

Even developers have bosses, and these are them; they own the building until it is sold to a long-term landlord. They write the checks that cover costs during the four-year lead-up to a big project. In exchange, they get a slice of its resale proceeds.

City parks, streets & water/sewer fees: $95/month (5 percent)

Known in Oregon as system development charges and elsewhere as impact fees, these are intended to cover the city’s infrastructure costs of serving a new population. We estimated they add up to about $21,500 per apartment unit. This also includes a 1 percent city excise tax on hard construction costs, used in Portland for below-market housing.

Property taxes: $205/month (10 percent)

In a city like today’s Portland, where housing rarely sits vacant for long, landlords happily pass property-tax costs on to tenants.

Construction and land lender: $214/month (11 percent)

It costs money to borrow money. The bank’s interest and fees might account for 10 percent of a project’s final rent, split close to 50/50 between an early land purchase and a later construction loan.

Previous landowner: $230/month (12 percent)

Commercial land near the hearts of the Northwest’s economic hubs usually has something built on it, so the price of land ($10.9 million per acre, in this case) must be enough to buy whatever was there before—in the Cordelia apartments’ case, a two-story office building. I used the value of a comparable nearby building to estimate this cost.

Property management company: $282/month (14 percent)

These folks clean the hallways, collect the rent, fix the boiler and sign new tenants. This also includes electric, gas and sewer bills.

Housing materials and construction: $656/month (33 percent)

This has been a great year to be a Portlander with a drywalling business. “Construction costs are at their apex,” said Kevin Cavanagh of Guerrilla Development. “Never been higher in the history of Portland.” I assumed $194 per square foot of living space for work done in 2016 and 2017. It came to about 34 percent of project costs, the biggest single share of today’s rent check – and also the driving force behind most of the other factors, from architects’ fees to bank loans. For every $1 that hard costs rise or fall, total project costs rise or fall $1.31.

How the math works

Three factors set the rent in a new apartment building: the upfront cost to develop and construct it; its operating expenses; and the return requirements of short-term and long-term investors.

To get built, a project needs to expect rents high enough to meet the investment goals of its long-term landlord—maybe a retirement fund thirsty to turn cash into a permanent revenue stream—after generating sale proceeds big enough to pay off early investors at high interest.

For example, TIAA-CREF, a teachers’ pension fund, owns the Cordelia Apartments. “Everyone hates Wall Street, but it’s just our parents’ retirement,” said Noel Johnson, a developer for Cairn Pacific, who happens to be the son of a teacher.

For this exercise, I imagined a project whose long-term landlord seeks a 5.8 percent annual return on an equity investment—known in the business as “yield on cost.” That ratio is different in different cities, based on where property values are heading over time; this is a typical target in Portland.

Using that 5.8 percent multiplier, I converted upfront costs—things like developers’ and architects’ fees, city fees and construction costs—into shares of monthly rent, then factored in operating costs like property management (including utilities) and taxes.

Nine ways to make apartments cheaper

Louis.1920.14thStreet.NW.WDC by Elvert Barnes used under CC BY-SA 2.0

Every Pacific Northwesterner seems to have an idea for making new apartments cost less.

Most of the ideas kicked around would actually work to some extent—but how much would each really save in the end? And how many of them would Northwesterners actually want?

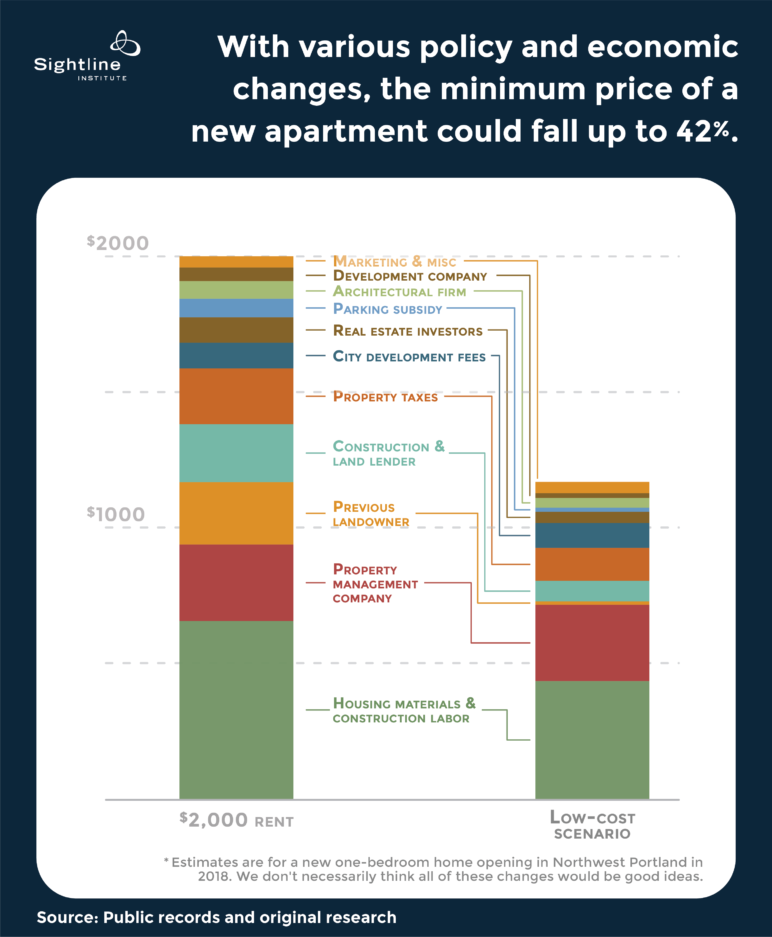

In the first part of this exercise, I broke out the different things a rent check in a new building has to pay for. Now, let’s examine nine things that could be done—or that could inadvertently happen—to bring those rent prices down.

Using the same figures as above, I ran hard numbers on nine scenarios that would save costs on a typical apartment that today rents for $2,000. Some are unlikely, others may be impossible and at least a couple have serious downsides. But all have come up in public discussions as the region has debated its housing problem.

Here’s approximately how much each would save.

Original Sightline Institute graphic, available under our free use policy.

Get investors to demand smaller returns: $31/month

Kevin Cavenaugh of Guerrilla Development says he’s fascinated by the idea that business leaders should be ruthless profiteers at work, then make up for it with charity. “You would club baby seals with your left hand and build an orphanage with your right hand—that’s how it used to work,” he said. But the developer said he’s trying to upend that approach with a new project on Portland’s Northeast Sandy Boulevard. Atomic Orchard, a mixed-use development with 86 rental units, is giving his investors lower rates of return and using the savings to include 18 below-market-rate lofts for people “working on the front lines of homelessness in Portland.”

Investors “can give me money, and they can do social good,” Cavenaugh said. A Portland where all investors asked for only 10 percent returns on early, risky real estate investments (rather than a more standard 15 percent) would be a Portland where the average apartment would cost about $31 less per month.

Pay development pros like elementary school teachers: $34/month

Do developers really need an average of $175,000 in annual pay?

Does the average architect really need $75,610?

I’ve imagined a world in which every developer and real estate consultant earned no more than the average Oregon elementary teacher: $65,250. (I also figured that the firms’ support staff and non-salary costs would be about the same.) If that happened, it could cut the rent by about $34 a month.

Cheaper materials and minimal common spaces: $52/month

Wood countertops. IKEA fridge. No lobby, let alone a gym or shared kitchen.

It’s an obvious option. But even the most skinflint developer would struggle to shave more than 6 percent of hard construction costs—it comes to $52 a month from the final rent—by skipping every frill. That’s why so many new buildings go the other direction and splurge on small stuff: amenities that read as “luxury” don’t actually cost much to add.

“Lipstick is cheap,” said Noel Johnson, a developer for Cairn Pacific.

Make Portland’s building permit process as efficient as Houston’s: $61/month

For a project like the Cordelia Apartments, every day a building permit awaits approval adds $4,825 in interest to a project that will have to pay back its lenders and investors, plus (in recent years) another $4,371 as construction costs climb. Each day of that process adds about 25 cents to the future monthly rent of each new apartment.

Over the past 15 years, the median building permit for a large apartment building in Portland took 237 days to review. That’s because each permit must be reviewed by 13 separate groups or bureaus, each with its own stack of rules. The back-and-forth takes months.

So I got numbers from Houston, which in 2015 redesigned its system so all city staffers could review plans digitally and simultaneously. (Portland has been promising a system along these lines since 2010; after numerous software delays, it’s expected by 2019 at the soonest.) Over the past three years, the slowest of Houston’s 5,974 new commercial building permits took just 28 days to process. If that were Portland’s average, the monthly rent in each new building might be $61 less.

Another benefit: a shorter processing period would also help projects avoid hitting the market when they aren’t needed, which could make buildings with thinner profit margins more viable.

Reduce car ownership: $78/month

Each parking space, including the aisles to reach it, eats up 350 square feet of space—more than a bedroom.

Even in inner Northwest Portland, the going monthly rental rate of $175 per underground spot doesn’t cover the cost of excavation and construction, so the rest comes out of everyone’s rent.

If fewer people had cars on site—say, one car for every five rooms instead of three for every five—the garage could be smaller, those savings would cascade into other cost factors, and average rent could end up $78 lower.

Reduce public services: $85/month

Ballots don’t lie: Portlanders generally like taxes. But taxes do affect rents.

Slicing local property tax millage from 2.5 percent of taxable value to the 1.5 percent rate in Roseburg, Ore.—which drew national attention last year for voting to close its last public library rather than hike taxes—could save $85 in monthly rent.

Slow the rate of construction cost increases: $141/month

Fact: unlike almost every other part of the manufacturing sector, construction workers have gotten less productive per hour since the 1990s.

That’s not because construction workers are worse at their jobs—it’s because the new technology that has let machinists, longshore workers and policy writers get more done per hour hasn’t arrived for construction workers. This a huge problem for construction workers (whose real wages have been stagnant) and everyone else. And it’s exactly the problem modular and prefabricated homebuilders are trying to solve.

I imagined a world where we’ve figured out how to make construction more efficient, letting building costs rise only 2 percent per year—so, at the rate of inflation—rather than the recent 8 percent or so.

Re-legalize small apartment buildings: $158/month

Two-story wood-frame apartment buildings were the Northwest’s answer to its 1900s and 1940s housing booms for a reason: They’re cheap to build. But in 1959, Portland became one of a flood of cities to declare them incompatible with low-density residential zones. If we wanted, we could re-legalize so-called garden apartments in R5 zones. Putting new one-bedroom apartments in a two-story wood building instead of a five-story concrete-and-wood one would slice construction costs from $194 to $159 per square foot, shaving rent checks about $162 per month.

One major catch: because shorter buildings require more land per home, Robert Cheney might need to find his apartment at, say, Southeast 26th Avenue and Lincoln Street, because land is cheaper there than at Northwest 19th and Johnson.

Reverse Portland’s population growth: $321/month

Portland’s modern growth spurt started in 1987; the population has grown more or less steadily since. Much of the Northwest has never known what long-term economic decline is like.

But no city grows forever. Someday Portland’s bust will come, jobs and people will drift away, and the city will see what a real housing surplus looks like.

To illustrate the impact that a radical reversal in Portland’s population-growth rate would have on rent prices, I slashed the cost of commercial land from the current $250 per square foot to $13—the going rate for commercial land in Toledo, Ohio, a city that in 1980 was roughly the same size as Portland but is now shrinking. That cost savings would knock about $321 off a rent check—and Portland would have a different set of problems to deal with.

TOTAL SAVINGS: $832

Approximate price of a $2,000 apartment if all nine of the above-listed savings could be applied: $1,168 per month, a 42 percent price cut.

Why new building prices matter…

The Square Apartments by Eli Christman used under CC BY 2.0

For the sake of simplicity, this project makes an important assumption.

It assumes that if developers save money on a project, they’ll pass on the savings to future tenants by lowering the rent.

In the short term, only the saintliest developers actually would do this. If other new buildings in the area still were charging $2,000 for a one-bedroom apartment, most developers would charge the going rate and pocket the difference.

But these savings start to matter in the long run. Every several years in a growing city, ambitious developers tend to build a bit faster than population growth —eventually forcing rents down slightly as property managers scramble to fill empty rooms. But then, as soon as developers realize rents have fallen, building slows until rents rise again.

That’s exactly what seems to be happening in Portland right now. It’s a boom-bust cycle that creates periodic housing shortages like the one that started seven years ago, triggered by the collapse of homebuilding during the global financial crisis.

For tenants, the long-term story is that unless there’s a local economic collapse, rents in private-sector buildings mostly go up, almost never down for more than a few months.

But this trap, perverse as it is, does have an escape hatch: lowering costs. If development costs fall, developers can keep “overbuilding” longer than they otherwise would because they can keep turning a profit despite lower rents. This drives rents permanently lower in all buildings before the cycle begins again.

“We’ll overbuild a little bit more,” said Portland-based housing economist Jerry Johnson of Johnson Economics. “Basically, rents are really set by replacement cost, and that’s why it’s important in the long term to keep replacement costs low.”

… And when they don’t

There’s one other limitation of this project. You already may have noticed it.

Combined, all these economic and policy changes reduced rent by a whopping 42 percent. But even after that, new apartments would still cost $1,168 per month.

If you were a 40-hour-a-week restaurant cook who makes $12 per hour, you might take home $1,600 a month after taxes. For you, that $1,168 rent might as well be $2,000. You couldn’t afford either amount.

That’s the other great challenge of modern housing: It’s essentially impossible to build housing to today’s standards cheaply enough for poor people to afford a newly built apartment.

This is a very, very important fact about the housing market.

The high cost of building new homes, even in the rosiest of circumstances, leaves two sorts of places where the poorer half of tenants can live:

- publicly subsidized homes

- buildings that are not new

Any healthy region needs both. But it’s option 2 that currently keeps a roof over the heads of about 85 percent of the Pacific Northwest’s tenant households, including 70 percent of those with incomes below $20,000. That’s why the price of homes in older buildings is even more important to affordability than the price of new ones.

As they age, Johnson said, older rental buildings tend to become gradually cheaper … but only if tenants willing and able to pay more—tenants like Cheney and his girlfriend—can find more desirable places to rent instead.

And that’s why the cost of raising up new buildings like the Cordelia Apartments ultimately sets the price of old buildings. If you could get into a newly built apartment for $1,800, or $1,600, or even $1,168, then landlords of old buildings nearby would have no choice but to charge less for theirs, too.

With publicly financed housing, the benefits are even more obvious. Cheaper building would mean more homes for every tax dollar we can raise.

Northwesterners have lots of options for starting to wrestle down the cost of building new homes. If we can find safe, fair ways to make it happen, every tenant in the region will win.

This story has been updated, improved and republished from an investigative series first produced by the Open: Housing Journalism Collaborative, a joint project of the University of Oregon’s Agora Journalism Center, Pamplin Media Group and KGW-TV.

The numbers in this report are a bit different than those in the previous version. That’s because I’ve modified the underlying spreadsheet to include more accurate nuance—for example, our model now scales development fees up and down with project costs, in better line with how developers get paid.

Look for other stories in this and related series at www.OpenHousing.net.

Jake Wegmann

Absolutely epic analysis.

R. John Anderson

If you would like to see developers perform the work for the same wages as school teachers you will need to come up with a way for developers to take on the same level of risk as school teachers. Is there a construction lender or mortgage lender who does not require the developer of a building to sign a personal guaranty for the loan on the building?

Michael Andersen

Our baseline scenario used a 5% developer fee on all costs other than land purchase and equity sales, which was intended to simulate a developer who had no equity stake of their own but faced some risk due to having their payments tied to three milestones in the process: the land purchase, the building permit issuance and the lease-up.

The low-pay scenario brought that down to 3%, based on the assumption that a developer working on this scale makes about $175,000 per year on average, that about one-quarter of that developer’s business costs are overhead and support staff (which we didn’t touch) and the remaining three-quarters are compensation for the owner/business partner. You could assume this drop in compensation takes the form of a change of heart on the part of every developer in which they’re willing to work for less on average despite the personal risk and income volatility, or if you prefer you could assume that developers are accepting the lower fees that (as I understand it) would come with a zero-risk contract job on behalf of another firm that was taking on full risk.

However, you’re right that even in the second scenario the inherent risk of development would remain, and the “other firm” (here best represented by the equity investors, I suppose?) would demand a higher rate of return on their early capital. This model doesn’t do a great job of capturing the risks of the whole project falling apart, which is obviously part of the development business. Of course, it also doesn’t capture the upsides of betting on real estate in a soon-to-be hot market, either. The goal is to help more people get a sense of scale of the costs and possible policy solutions here, not to capture every detail precisely.

KAC

This was an interesting and informative article. Reading it brought this question to mind: Since the overwhelming majority of new apartment construction appears in the form of simple (and nearly identical) box structures, why are “architectural fees” so high? It seems to me that – given nearly identical designs – an “off the shelf” building plan and pre-manufactured and interchangeable components – would substantially lower costs. Can the author please provide a perspective on this question?

Michael Andersen

I think an architect would be better equipped to answer this question, but I don’t think the bulk of an architect’s work on a building like this is in its external look and feel so much as in the internal arrangement of rooms, utilities, etc., and all the materials decisions required throughout the structure. So yes, to the extent that that can be standardized with modular construction or design, then I’d agree that’s a possible cost savings. I assume individual architectural firms have strong incentives to use standard designs that they apply from one project to another, but I don’t know for sure.

One thing to note here is that I’ve lumped a bunch of the “soft costs” associated with the development process, such as permitting and other regulatory compliance, into the payment to the “full-service architecture firm.” If this line item were for the architectural work alone, it’d be maybe half as big but somebody would need to do the other work, too.

R. John Anderson

Just because building look similar does not mean the same plans are able to be reused at some great savings. A licensed Architect who stamps the permit drawings for an apartment building carries the liability for that design and their construction observation until they die. They are not able to limit their personal liability through a corporation or LLC. That risk costs money.

Jim Labbe

As we debate raising our property taxes to pay for a regional affordable housing bond measure, I am curious about the assumptions that go into the 10% contribution of property taxes to apartment rent in this analysis. Are you assuming all property taxes get passed on all of the time? Did you explore the debates among economists about property tax incidence?

In terms of mitigating measures what about some of these:

1. Expand or modify existing property tax deferral programs for seniors and the disabled to the help low income renters. For example Baltimore has a program that provide tax credits to renters.

2. Shifting property taxes from improvements to land to reduce the per-unit cost of property taxes on units (the land tax solutions).

Rick Hawksley

So according to this logic an architect should reduce their fee because they make too much money? (And probably already would have a hard time renting one of these apartments) Salaries account for 1/3 of the cost of running a firm. The people marketing make more money Than the people who do all the design and engineering…. you are looking at it completely backwards. As Bernie Sanders is fond of saying, “people’s salaries are too damn low.”

Michael Andersen

The point of including the architecture fee, or the marketing fee, or any of these items that we included, is not to say “this should be slashed to the bone!!!” but rather “here’s how much savings we could get out of each of these if we could somehow figure out a way to slash them to the bone.” Then people can decide for themselves how likely it is, what the benefits would be, and whether it’s worth trying.

Richard Walker

Michael, While I enjoyed your analysis of this situation and the associated spreadsheet, sadly your comments about the hypothetical architect and developer’s fees are dangerously naive. Your comments about the developer and architect compensation are absurd, make me question your knowledge of the subject matter, and renders the entire exercise worthless.

It would be interesting to make an adjusted comparison between the average salary of a teacher vs. the average architect’s salary. Please keep in mind that the average architectural firm in the United States is a private small business with a total of 6 people. The average Architect does not have generous health and pension plans as the average American Public School Teacher does. Most architects work around 55 – 60 hour weeks for decades with little time off. Many architects work into their late 70’s because they cannot afford to retire. Compare this to a teacher’s calendar that provides summers and holidays off and in Oregon a teacher may earn full retirement with a pension at 58. As an architect, I have never had a Columbus Day or MLK day off and never been able to take more than 2 consecutive days off in the summer without being inundated with emails, texts, and phone calls.

I would like to thank you for your hypothetical assertion to “pay architects and developers like elementary school teachers”. Most American architects would take you up on this offer. Sadly it would also raise the fee you have plugged into your spreadsheet.

Kit

The cost of parking is only a $68 subsidy because in Portland it has been decoupled from rent, and it is a choice. In most jurisdictions parking is required, and included in the rent whether you own a car or not–so everyone is paying the full cost of parking: $175+$68= $243.

Michael Andersen

Good eye! This is correct.

RANDY JACOBSON

Nice graphic, comprehensive take and likely not very accurate. If you’re doing an article about rent then use apartments not a house for your data source. I don’t have deep knoledge of every category but the one I do, architecture is highly overstated as a portion of rent. That leads me to believe the methodology is also flawed elsewhere.

Architecture and engineering fees are higher for houses than for commercial scaled projects and that fee is a percentage of hard costs not hard costs and soft costs. SInce the takeaway this research is that soft costs imposed by municipalities to ensure quality developments that pay for externalized costs not usualy paif dor by developers that’s a big mistake.