When Stefan Schmidt is recruiting a new mid-level employee, he draws a circle in his mind: a 45-minute driving radius around the North American headquarters of his company, LPFK Laser and Electronics.

Each year, it seems, traffic congestion makes that circle smaller—and good family-wage jobs at LPFK get more likely to sit empty as he searches for applicants.

“Junior salespeople, somewhat recent grads—these folks can’t afford to live in this area,” Schmidt, LPFK’s president, said this month. “They’d be in the street.”

LPFK has 32 local employees and is the sort of small, growing, specialized employer that every suburb hopes to build its local economy on. For the last 10 years it’s been based in Tualatin, Ore., five miles southwest of Portland’s city limits.

Tualatin, population 28,000, is a familiar flavor of suburb in the modern Pacific Northwest: tech-powered, job-rich and home-scarce. It’s a smaller sibling of Hillsboro, Redmond or Burnaby.

But what makes Tualatin remarkable is that it may be in the early stages of doing something none of those cities have done yet: carving a new path for how a suburb can grow fairly, happily and affordably.

Tualatin’s rents have grown six times faster than Portland’s, study estimates

Tualatin Commons by M.O. Stevens used under CC BY-SA 3.0

Tualatin has seen one of the worst housing shortages in the Northwest over the last four years. Four weeks ago, out of 54 cities tracked in Oregon and Washington, the respected data report from ApartmentList.com ranked Tualatin 54th for keeping rents stable since the company’s data set began in 2014.

In those four years, estimated monthly rent in the median two-bedroom home in Tualatin has soared 47 percent, to an average of $1,881 over the most recent three months. That compares to a 7 percent increase in Portland (to $1,330) over the same period.

For owned homes, the price spike has been only a bit less sharp: 39 percent in those four years, Zillow estimates. A 10 percent down payment for a high-interest mortgage on the median Tualatin house now requires $46,000 in cash.

Housing shortages aren’t unusual in today’s Northwest. But this one is a big economic problem for Tualatin—big enough that business leaders like Schmidt have been talking seriously about how to solve it.

What is unusual is that this year, those business leaders are finding some unexpected allies: Tualatin residents like Daniel Bachhuber.

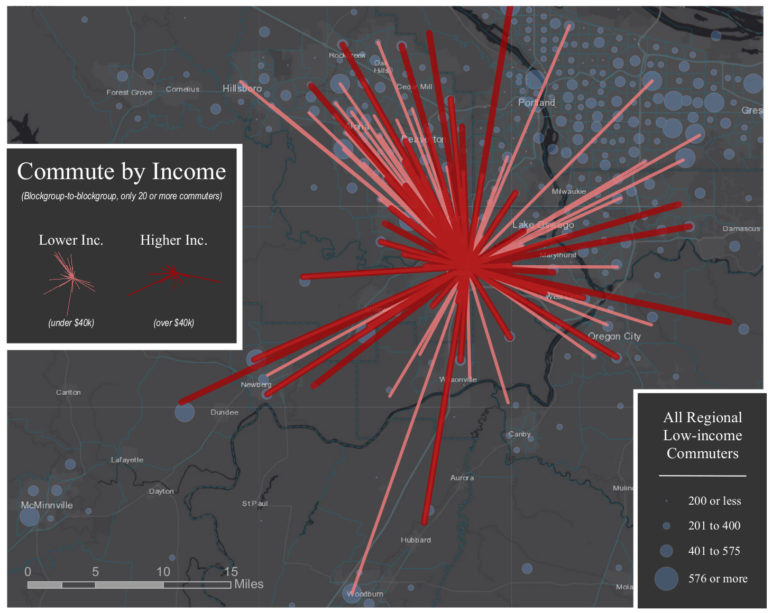

Tualatin’s traffic problem is a housing problem: Jobs have grown 37 percent faster than homes

People of all incomes currently commute to Tualatin from all directions, often from significant distances. Red lines represent commutes to Tualatin of people making more than $40,000; pink lines represent people earning less. Image and 2015 data courtesy of Institute of Portland Metropolitan Studies, used with permission.

Bachhuber stood on the carpeted dais of the Tualatin Heritage Center and talked to the Business Advocacy Council of the Tualatin Chamber of Commerce about his home search.

“In three days, there were 27 offers,” he said at the meeting last month, describing his bid for a house in Southeast Portland. “We bid $50,000 over and the winning offer went for $150,000 over.”

When the 31-year-old software developer who is a father of two describes himself as a “long-term Tualatin resident,” he’s talking about his childhood and a hoped-for future. He and his family finally landed a house there in 2015.

But once he returned to the area, Bachhuber realized, some things had changed since his youth. There were almost no other young families. That’s part of what led him to instigate last month’s event with other people worried about the future of Tualatin’s prosperity and quality of life.

For the moment, Tualatin’s prosperity seems bulletproof. Its median income is $71,896, 30 percent above the national average. The poverty rate is 8 percent, three points below the national average. Unemployment is 3.1 percent, thanks in part to successful local employers like LPFK and others.

But for its companies to keep thriving, they need to be able to fill new positions, said Linda Moholt, executive director of Tualatin’s chamber of commerce. And that requires more housing than Tualatin and its neighbor cities have been building.

“If you have housing, talent will come for the jobs we have,” Moholt said.

Tualatin and its neighbors around Washington County have a lot of jobs. Since 2000, the county has added 82,000 new jobs, but only 42,000 new homes. In all, the job growth rate has been 37 percent faster than housing growth over those two full business cycles.

All that has left employers like Schmidt stuck, trying to convince young professionals to either spend 90 minutes in the car every day or else pay a premium to live in the sort of neighborhoods they don’t seem to prefer.

“They like to live in Southeast Portland or something like this,” Schmidt said. “Commuting here from Southeast Portland is not a pretty picture.”

Tualatin is already rewriting its zoning code—it could rethink it, too

An example of Tualatin’s code rewrite process. Photo courtesy of City of Tualatin, used with permission.

Tualatin has a few big opportunities coming up to tackle this problem. One: more land is on the way to opening for development. Another: the city is rewriting and simplifying its zoning code for the first time in almost 40 years. After that’s done, in 2019, Tualatin is planning to rethink and tweak the policies behind its code, too.

“All the zoning right now is designed around a single style of housing,” Bachhuber said. “And I think that across the board, bringing in more housing options wherever you can is going to be the only ticket out.”

More options might mean taller apartment buildings, or legalizing “missing middle” housing like duplexes and triplexes in soon-to-develop areas.

Bachhuber and Moholt also say they’re interested in a newer solution: Finding ways to disperse more homes around the city in converted garages and backyards. A 2017 state law made accessory dwelling units legal in Tualatin and most other Oregon cities, but it’s up to cities to set all-important details that determine whether they actually get built.

ADU reform is hot in Cascadia right now. Places from Bellingham to North Vancouver to unincorporated Longview have been considering changes to legalize or encourage them. Moholt even sees them as something that could help her own family.

“We have an oversized lot,” she said. “The kids would move into ours when they’re ready for children, and we could move into the little one.”

Bachhuber doesn’t see ADUs as enough to solve a regional housing shortage on their own. “Like many complex social challenges, there aren’t any ‘silver bullets,'” he wrote last month. Instead, they’d need to be part of a sheaf of new ideas for growing Tualatin without growing into something the city’s residents would dislike.

But the truth is that change is probably coming to Tualatin one way or another. Either it’ll keep getting more and more dependent on out-of-town commuters and the endless roadway expansions to move them in and out; or it’ll find a way to let more people share Tualatin’s prosperity directly.

And if Tualatin can chart that second course, it’ll once again be more than just another well-to-do suburb. It’ll be a guide to the possible future of the Pacific Northwest.