A new set of maps created by Neil Heller reveal a surprisingly dark pattern—and show it’s still shaping how the economic, social and natural wealth of our cities gets distributed.

Many Pacific Northwesterners know that duplexes, triplexes and other “gentle density” housing remain common in older parts of our cities even though they’re usually illegal to build today.

Less discussed is the fact that even in cities where building small detached homes used to be common, some of our older neighborhoods have few such housing options.

A new set of maps created by Portland housing-options advocate Neil Heller reveal some of this surprisingly dark history—and show it’s still shaping how the economic, social and natural wealth of our cities gets distributed.

Here’s a map of Portland with industrial, parkland and high-density areas grayed out. Each red dot is a building that includes between two and eight homes: a duplex, triplex, fourplex, or small apartment building.

“Gentle density” housing is clustered in Certain Portland neighborhoods.

Red dots are lots with two to eight homes. Residential and commercial areas are in white. Map by Neil Heller. Data source: Metro.

As we’d expect, these sorts of homes are clustered in older neighborhoods near the city center — but not in all the older neighborhoods.

Within the city’s vast expanses of residential neighborhoods, several areas almost seem airbrushed out. Red dots of duplexes, fourplexes and garden apartments surround them; within them, few dots appear.

I asked Neil if he could draw boxes around a few of these duplex deserts.

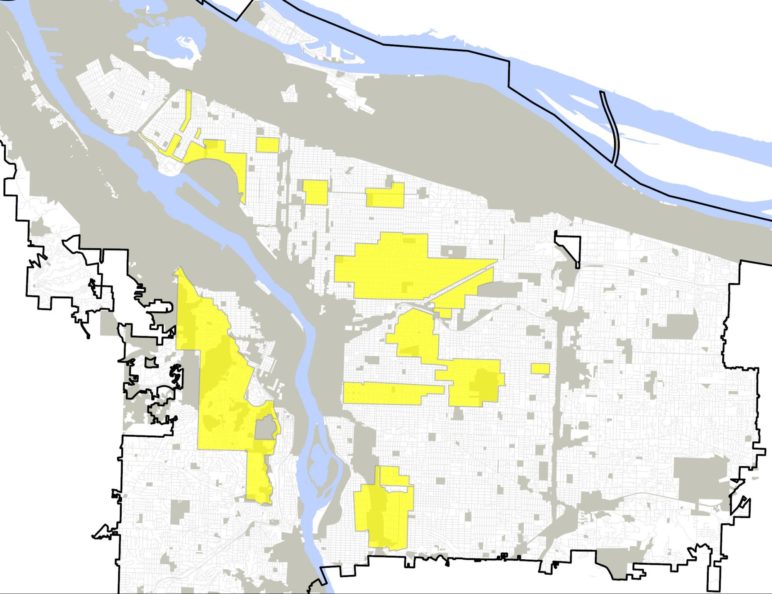

Some Portland neighborhoods have Many fewer small-scale housing options.

What’s going on in these areas to block duplexes and other smaller-scale housing options? Map by Neil Heller.

If you’re familiar with Portland, you might know these areas by name: the West Hills, Irvington, Alameda, Laurelhurst, Eastmoreland, Mount Tabor, Arbor Lodge.

What’s the deal?

The answer lies in 1924—the year Portlanders passed their first housing ban.

Portland’s first exclusionary zoning

It was in 1924 that Portland voters approved the city’s first zoning plan in a citywide vote, four years after having narrowly rejected the idea.

It was a turbulent moment in Oregon politics. In 1922, the resurgent Ku Klux Klan had swept to electoral victory across the state, putting its members in the governor’s mansion, the House speakership, and controlling the Multnomah County Commission. In 1923, the Klan-backed Alien Land Bill, banning Japanese nationals from owning property in Oregon, sailed through the Klansman-led state legislature with just one dissenting vote.

A parallel national movement was afoot. A White House task force convened in 1921 was pushing US cities to pass zoning codes. The task force’s official documents never mentioned race, but its members were “outspoken segregationists” who (as documented by Richard Rothstein) wrote elsewhere that zoning could help segregate people by race.

This was the political environment when Portland’s real estate brokers brought a revised zoning plan back to voters for another try. Authored by H.E. Plummer, who served as a planning commissioner and head of the city’s bureau of buildings, the 1924 plan was approved with 60 percent of the vote, and formally separated industrial and residential development. And it introduced another idea, too: “single-family” zoning, which required households who wanted to live in certain parts of town to be able to pay not only for a home but for a certain minimum amount of land around it—at least 5,000 square feet in most cases. Other sorts of homes would be banned.

Who decided where the housing ban would apply? According to Lloyd Keefe’s history of Portland zoning, the city tried to refer the decision to “a majority of property owners” in each area by creating single-family zones whenever a petition or community club requested one.

Portland’s first 15 single-family zones, from which attached homes were banned at the request of property owners of the day, are featured in the map below.

Portland banned attached homes from 15 neighborhoods between 1924 and 1959.

The first 15 areas where duplexes or apartments were made illegal, put in place between 1924 and 1959. Map by Neil Heller.

Look familiar?

OK, I cheated. For the previous map, I didn’t really ask Neil to outline the areas without many dots—I just asked him to drop in the outlines of these zones from 1924. That’s because the correlation is striking. You can see the ban’s effects on every street in most of these areas today—94 years later, they have very little variety of housing at all. It’s one lawn and driveway after another.

A few duplexes, triplexes and small apartment buildings have sneaked into these areas since 1924, thanks to loopholes or upzones along major streets. But it’s nothing like the change outside their borders.

The impact of Portland’s 1924 zoning plan remains apparent to this day.

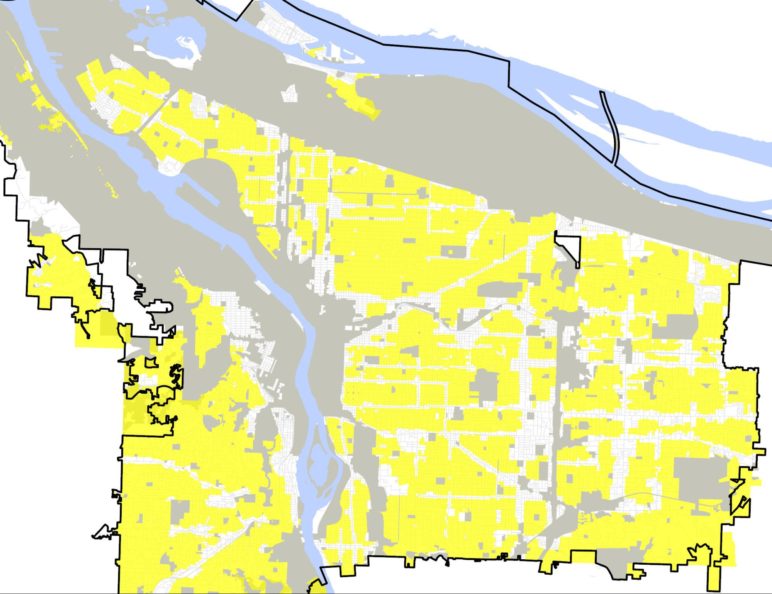

Then in 1959—incidentally, 11 years after the US Supreme Court declared “racial covenants,” race-restrictive clauses in housing deeds, “unenforceable”—Portland tried something even bigger. It expanded its ban on attached housing to almost every neighborhood. The map below displays where the ban applies today.

Portland expanded its ban on attached housing to cover most of the city.

As a result of Portland’s 1959 redefinition of low-density zones, duplexes and apartments are now banned from all the areas in yellow. Map by Neil Heller.

Today, this is more than just a matter of how neighborhoods look. Ninety-four years after the 1924 ban on attached homes, Portland’s first single-family zones are clearly visible in neighborhood income levels.

Highlighted in blue in the map below is every Census block group in Portland with a median income over $60,000 (darker blue blocks have median incomes over $95,000).

There is a striking correlation between Portland’s zoning and median incomes.

Blue areas are Census block groups with median incomes over $60,000. Dark blue are blocks with median incomes over $95,000. Map by Neil Heller. Data source: U.S. Census Bureau.

Again, the similarity is striking. There are a few ways for a neighborhood in the Portland of 2018 to be reserved mostly for the well-off. But one of the most effective ways seems to be “ban attached housing in 1924.”

Portland’s first exclusionary zones and high-income areas overlap.

Portland’s highest-income Census block groups mapped against its first 15 exclusionary zones. Map by Neil Heller. Median income data: Census American Community Survey.

It turns out that when you make it illegal for someone to live in an area without also paying for an entire city lot of land, the only people who can live in that area are the richer ones.

Does this exclusion persist because Portland homeowners sympathize with the Klan? Of course not.

Here’s how it works: The classist and possibly racist impulses that convinced a majority of Portland voters to start banning certain types of housing in the 1920s carved patterns of segregation into city laws and, eventually, into unconscious assumptions about what is and isn’t normal in a city. Indeed, I bet almost all of us Cascadians now unconsciously assume it’s normal for large swaths of a city to have nothing except detached homes surrounded by yards.

You don’t have to be racist or classist to live in a neighborhood shaped by racism and classism.

But whoever you are and whatever neighborhood you live in, your life is still being shaped by the ways these forces shaped your neighborhood.

Portland may partially reverse its 1924 and 1959 mistakes

As we’ve been reporting, Portland (like Minneapolis) is currently considering an end to this ban on duplexes and other gentle density citywide—not only in the parts of the city where attached housing was legal until 1959, but also in the parts of the city that have almost no attached homes because they were banned in 1924.

Among those backing this re-legalization at the planning commission this month were some Portlanders whose ancestors, if they’d lived in Oregon, would have been forbidden to own property.

One was Danell Norby of Anti-Displacement PDX. She spoke on behalf of her part of town, East Portland. Re-legalizing small attached housing there, she said, would both allow “outer areas the density needed to support additional amenities” and give nonprofit developers more tools for preventing displacement.

“These policies will help determine whether or not Portland’s spoken commitment to racial and economic diversity is actualized,” Norby said. “The current proposal blocks the development of badly needed, comparatively affordable infill housing even as market forces displace families from these neighborhoods to Gresham, Vancouver, Washington County, and beyond.”

And Chris Chen, currently a homeowner in the Eastmoreland neighborhood, spoke on behalf of his own personal history — how he’d built his life as a young Portlander by living in the sort of small, attached homes that the city started banning in 1924.

“Over 10 years ago I moved into my first Portland home, a courtyard studio apartment on Northwest 20th Avenue,” he said. “Later I moved to a garden apartment by Balch Creek, and then to a four-plex where I watched the Chapman Swifts from my living room window. And every breakfast featured the sounds of families walking their kids to school. The irony of this Portland story is that the structures I used to call home are illegal to build today.”

Chen said Portland has a chance to “deliver transformative justice by re-legalizing and providing diverse housing choices for a diverse population — and in so doing, begin to reverse a century of exclusionary policy.”

As clearly as Heller’s maps, Norby and Chen’s testimony showed why zoning maps are moral issues, shaping local lives for generations to come.

But by mentioning the benefits of gently denser neighborhoods, Norby and Chen also highlighted what Portlanders, like all Cascadians, have to gain by re-legalizing small attached homes everywhere.

In the end, it’s the difference between requiring neighborhoods to look like this:

And making it legal for them to eventually look more like this:

The first house on the left has one unit inside; the second is a duplex. Buckman neighborhood in Portland. By Michael Andersen, used with permission.

For most Cascadians, is this really a difficult choice?

Jim Labbe

Michael: This is an amazing, revealing piece of writing and research. Thanks again. I have made this plug to you before, but I am curious, how the politics of zoning evolved from the single/land tax tax politics of the previous decade in Oregon. Oregonians voted on measures for or toward a single tax on land via ballot measure at almost every election after (1908, 1910, 1912, 1916, 1920, and 1922). After pioneering the establishment of the initiative and referendum system in 1902, Oregon in general and Portland in particular became ground zero for the national movement for a Georgist single tax debate. As historian Robert Johnson notes in his book “The Radical Middle Class” on progressive-era Portland, “in every election nearly one of four Portlanders voted for the single tax , and at times that figure reached much higher.” There are lots of interesting overlap in the precinct maps on these votes (detailed in Johnson’s book) and the early zoning maps you reveal in this article.

Michael Andersen

Jim, thanks so much. I still love this idea and now that my scope is a bit broader, I’m hoping to be able to get into it eventually.

Fact Man

The “history” you cite is about 50% false, as is the neighborhoods you try to shame. Try looking at your maps a little closer and you will realize that some of the ones you named don’t match your maps, or your weird and false narrative.

Michael Andersen

I’m not trying to shame the residents of the neighborhoods, only their history. But which ones are you talking about? The 1924 borders aren’t identical to today’s official neighborhood boundaries, of course.

Obviously I want to correct any errors quickly, so it would be great if you could let me know what you think is wrong.

Nick Olson

Great work thank you for the reporting

Christopher Wilson

I live in Laurelhurst. It was founded in 1910 and had restrictions on the types of structures that could be built. Only single family, schools, and churches. 1924 had no effect here. There aren’t a whole lot of duplexes and triplexes but there are converted basement apartments and ADU’s in garages that are rentable to the general public. In just one block of my house I have one brand new basement apartment, and 4 garage conversions. The upcoming historic district doesn’t say no to any of this density. Keeping the houses, garages, and trees while adding people. Tearing everything down to add in 1 more house here and one more there isn’t a solution. It’s just greed from developers. The majority of house demolition in Portland is one for one.

Michael Andersen

As discussed in the piece, laws and people not intended to be racist or classist can have effects that strengthen racism and classism. It’s great that Laurelhurst has added some housing variety in the form of ADUs, etc. But other, less exclusive areas immediately outside Laurelhurst are able to add more variety. And further away, along 82nd Avenue for example, the city has allowed great variety of housing types (and as a result expects quite a bit of demolition under the status quo).

But for good and for bad, legalizing fourplexes (or whatever other small-scale housing) wouldn’t mean that everything suddenly gets replaced by fourplexes. Portland legalized corner duplexes in 1991, with a de facto building size cap of more than 6,000 square feet. In the 28 years since, only 3.5 percent of affected corner lots have developed as duplexes. Portland’s re-legalization would almost certainly have an even smaller effect, because building sizes, even for fourplexes, would be capped much lower than that.

This is mostly a conversation about what happens to buildings when they reach the end of their natural life: either they’ll be replaced by one bigger home or by a few smaller homes.

Kris Bakouros

Development of lots is dictated by the zoning designation applied to the lot by the Dept of Land Use: see Zoning Code. Most developers would prefer to build on CM3 lots v. R5. However Land Use Review appeals are hugely expensive and uncertain. The arbitrary and unfitting zoning designations on many inner city lots are ultimately damaging if the goal is to create “gentle density”.

Mark Bello

Do you want to preserve Portland’s tree canopy? Then please consider where the trees grow, if the the only yards left are five foot strips along property lines?

Portland’s problem is a lack of site review, that balances needed density with opportunites for nature to thrive.

These can be non discretionary regulations like mandatory minimum yards dimensions rather than car parking. That avoids design review and delays to the developer.

Comprehensive reform includes site design as well as loosening maximum density standards in my opinion.

Thanks for a thoughtful argument.

Mark Bello

PS I remember downzoning Buckman neighborhood and considereing that a victory for the people.