Author’s note: Jameson Quinn and Jack Santucci have pointed out this method was proposed in 1884 as “The Gove Method.”

Here at Sightline, we’re fans of proportional representation, including multi-winner ranked-choice voting. We recently conducted focus groups to find out what voters in Oregon and Washington think about proportional representation. (Sightline director of strategic communications Anna Fahey will write more about these focus groups soon.) Overall, we found out that voters across the ideological spectrum:

1) think we need to change our broken systems,

2) like the idea of proportional representation, but

3) don’t like the methods for getting there.

They don’t like party list methods because: parties. And they don’t like ranked-choice methods for two reasons. These two reasons are the key political problems with getting ranked-choice voting (RCV) implemented. First, voters perceive RCV ballots as more complicated than “pick one” ballots—which they are, though not so much that voters do not easily master them when a jurisdiction switches to RCV, as Sightline’s Margaret Morales will write about soon. Second, to make the most of an RCV ballot, voters must be more knowledgeable. They don’t just pick one favorite; they can rank all or several of the candidates. This perception is also true, and it becomes more true in multi-winner races with more candidates on the ballot for voters to parse. Again, though, the vast majority of voters quickly adapt to RCV ballots and fill them out adequately, as Margaret will write about.

To adopt RCV in most Cascadian jurisdictions would require a vote of the people, so these perceptions could be deal breakers for the entire system. To overcome them, reformers might adopt two strategies. The first is to educate voters enough that their perceptions change and they support proportional representation—probably in its RCV form, because our focus groups were either split on or opposed to party lists. The second is to actually solve the problems with RCV: to make a voting system with a ballot that is simple and in which voters do not need to be more knowledgeable than they do under Cascadia’s prevailing “pick one” electoral method.

In most of my work, I’ve focused on the former of these two strategies: educating voters. But the focus groups made me think long and hard about the latter option. Is there a way to use a simple and familiar ballot to achieve proportional results?

Well, eureka! I’ve landed on something that fits the bill. Today, I am describing it and asking for your reactions.

The answer is a hybrid of “pick one” and ranked-choice voting. Or rather, it’s a way to get proportional results from a pick-one ballot. Let’s call it “delegated ranked-choice voting.” In delegated ranked-choice, voters choose their favorite candidate, but they do not rank the others. Therefore, voters don’t need to study all the candidates and figure out who is third and fourth and fifth—just pick their favorite, as they’re use to doing. Then, the candidates themselves rank-order all the other candidates and publish the list before the election. Each eliminated candidate’s votes transfer according to his or her published preferences. Voila! Proportional results from a “pick one” ballot.

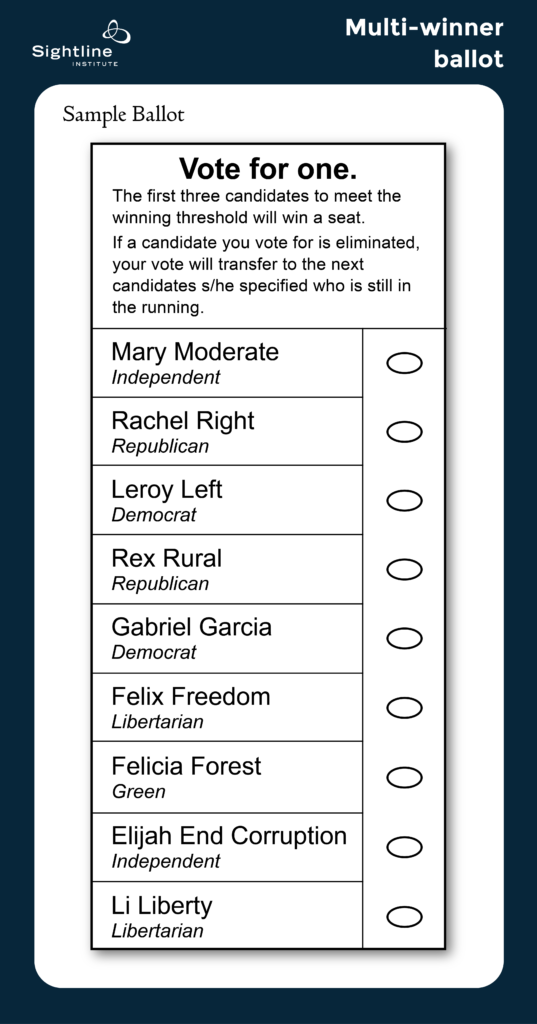

For example, imagine a three-winner Washington state legislative district with the fictional candidates on the sample ballot below. Your ballot looks exactly like it does now and you only have to pick one candidate, but you are free to choose your favorite even if he is not a front-runner, confident that you won’t waste your vote or spoil the race. You vote for Elijah End Corruption, but he gets the fewest number of votes—just 6 percent—and is eliminated. His votes transfer to the candidate he considered to be closest to him and whom he rank-ordered first—Mary Moderate. She already had 20 percent, so with Elijah’s transferred votes she passes the 25 percent threshold of exclusion for a three-winner district and wins one of the three seats.

Original Sightline Institute graphic, available under our free use policy.

What it would mean for voters, compared with the current pick-one system

Compared with the current system of voting in most parts of Cascadia, voters’ ballots would be simple and familiar. You would only have to know your one favorite candidate. Even if you didn’t have time to research all the candidates or check all of their rank-ordered lists, if you know that Mary Moderate shares your values, you can trust she will transfer your vote to another candidate who shares your values. After all, who knows the other candidates better than Mary? She’s been debating them at forums and interviews for months.

Additionally, you would not have to strategize about whom to vote for based on how they are doing in the polls, because your vote would still have a chance to count even if your favorite got eliminated (meaning that all her votes would transfer to her preferred candidate who is still in the race) or even if she didn’t need your vote because she won in a landslide (meaning that her excess votes would transfer to her preferred candidate).

Finally, you would know that your vote for a minor-party candidate would give that candidate power in the election, even if he didn’t win. In other words, you get all the benefits of ranked-choice voting; you just don’t have to know as much. How would you feel, as a voter, with elections run in this way?

What it would mean for voters, compared to an RCV system

The upside of delegated RCV compared to regular RCV is the delegation: many voters do not know enough to rank all the candidates with confidence (as in regular RCV), and they might not trust a political party to transfer their vote to someone else in the party (as in Party List), but they might trust their favorite candidate to rank her competitors. The downside is also the delegation: compared with regular RCV, delegated RCV ties the hands of those voters who know exactly what they think about multiple candidates.

Imagine the 2016 US presidential election used delegated ranked-choice voting. You voted for Sanders, and he ranked Hillary as his first alternate. So, when Sanders was eliminated after the first round, your vote was transferred to Clinton. Now, if you thought that was fine, then delegated ranked-choice worked well—you picked your true favorite, and your vote still counted in the final round. But if you were one of the US voters who liked Bernie Sanders best and Donald Trump second, then you would not be happy about your vote transferring to Hillary Clinton, your least favorite candidate. In short, the upside for less-informed voters is a downside for super-informed voters, and the tradeoff seems inherent in the system. Is it a tradeoff worth making?

What it would mean for candidates

Just like in ranked-choice elections (and unlike the current predominant system in Cascadia), candidates would have an incentive to run positive, issue-oriented campaigns rather than negative campaigns. If they made their lists public before the election, candidates would likely negotiate with other candidates to form alliances during the campaign.

And just like in RCV, minor-party or independent candidates would not be shut out of elections. They could run because voters could vote for them without fear of wasting a vote. And even if a minor-party candidate didn’t have quite enough support to win a seat, she could still influence a more mainstream candidate’s agenda by insisting he commit to certain policies or principles before she would agree to rank him.

Variations: How many votes do you get?

In the simplest version, which I’ve been discussing so far, voters get just one vote so the ballot looks just like a plurality ballot. But some variants are also possible, and I’d love to hear your thoughts on them in the comments section at the end of the article.

In a multi-winner race, say, a five-winner district, you might be disgruntled to have to pick just one. Instead, you could get, say, three votes—not an overwhelming number, but enough to empower you to express your preferences. The ballot might look like the one below. Many Oregon voters already have a ballot that says “Vote for Three” in city races so this would be a familiar ballot for some Cascadians. Alternatively, you could get the same number of votes as there are seats available, so in a five-winner district, each voter would get five votes.

Original Sightline Institute graphic, available under our free use policy.

Using seven votes in one race could be overwhelming for some voters, but their options could be simplified by counting the ballot like Equal & Even Cumulative Voting (used in Peoria, Illinois): if a voter had three votes but only filled in one bubble for Mary, all three of her votes would go to Mary. (If that sounds like it is violating the principle of one person one vote, you can think of it as each voter has one vote but is allowed to split the vote three ways or just cast it all at once for one candidate.) If Mary got eliminated, all three of her votes (or her one entire vote) would transfer to Mary’s top-ranked candidate who is still in the running. It’s an elegant approach that ensures all voters have equal power, even if some voters feel strongly about one candidate or aren’t familiar with more candidates or just didn’t realize they could fill in more bubbles. What do you think about using this method?

Another possibility: use a ranked ballot and voters could rank if they want to. If their rankings are exhausted (all their ranked candidates get eliminated) then it switches to a delegated ballot, and their vote gets transferred based on their last-ranked candidate’s preferences. This would take away the benefit of the simple, familiar ballot. But perhaps the ballot could be limited to three rankings rather than enough to rank all candidates, so it would be simpler than it might otherwise be while still ensuring your vote would count even if your top three choices are all eliminated. It could go along with an education campaign letting people know they truly only have to rank one candidate and their vote will still count. It shifts the tradeoff towards the high-information voters. What do you think about that?

More variations: How do candidates indicate their preference order?

My main idea is that candidates would publicly list their respective rank-orderings of candidates ahead of the election so that voters could see them. This approach offers several advantages. A super-informed voter could check to make sure he agrees with Mary’s choices for transferring his votes. A candidate’s ordered list could give that voter more information about how closely aligned she is with his interests, based on how high up on her list his other favorite candidates appear. Also, the votes could all be transferred and counted immediately after the election.

A second option is to allow candidates to use their votes to negotiate amongst themselves after the election. Electoral theorists Charles Dodgson (a.k.a. Lewis Carroll), Warren Smith, and Forest Simmons have all proposed this method, called Asset Voting, where each candidate uses his votes to horse-trade with other candidates after the election. For example, a candidate with a significant block of votes might exchange them for a promise that he will be appointed to a position he wants.

My guess is that Cascadian voters would balk at the idea of handing over their votes for politicians to barter with and would reject a system where they perceived politicians were choosing each other instead of voters deciding, but who knows? This method would also delay election results as candidates would need time to negotiate after the votes were in. Which of these approaches seems smarter to you?

What do you think?

Electoral reform will probably have to come from a vote of the people, since elected officials are usually loathe to change the rules that got them elected. Proposed reforms, therefore, need to appeal to a majority of voters. Party-based proportional representation definitely doesn’t. And ranked-choice voting faces a headwind. Could delegated RCV offer enough familiarity to most voters that an “delegated ranked-choice voting” initiative could garner a majority of votes? Is there a better name for it? Something less jargony?

At this point, delegated RCV is just a spitball with no empirical evidence about how voters or candidates would actually respond. Tell me: what pitfalls do you see? What am I missing? What opportunities can you imagine for road testing it in the real world to gather information about how it works in practice. Might high school and college student body elections give it a try? Professional organizations? Would someone build an online simulator so that membership groups could easily try it out?

Central to my inquiry, though, is this: Is this idea a better way forward to get proportional representation in North America? Or is it a dead end? I welcome your thoughts in the comments below.

Pete Ronai

I like your first alternative, with the candidates publishing in advance where their votes would go if they were to be eliminated.

Ken

Proportional representation has the effect of “locking in” the status quo. See New Zealand’s experience – their FPP, unicameral system allowed the Labor Party to enact sweeping (anti-labor) reforms in the 1980s, but the switch to an MMP system made it all but impossible to overturn those reforms.

*Any* system can be gamed. If you want to take on the major drivers of political dysfunction in the US, try looking at Sta Clara County v Southern Pacific Railroad, or Buckley v Valeo. These are far more insidious than whether we have two parties or twenty parties.

But that’s beside the point. I’m still trying to grasp why this entire issue area is within Sightline’s mission or vision. After all, having twenty parties doesn’t make anything inherently sustainable.

Rob Briggs

This voting and representation topic is much more complex and interesting than I had realized before this series. My response to Ken is: Democracies don’t engage in wars of aggression or drive themselves off of climate cliffs. Given the scale of corruption and dysfunction in our political system, restoring a functioning democracy appears to be a necessary precondition for success in pursuing almost every aspect of sustainability. This is some of Sightline’s most important work.

Rhys

So Ken, is it that the switch to MMP was kind of like suddenly stopping a pendulum, in the position it happened to be in? I guess I could imagine that scenario, where getting rid of the two party system suddenly would diminish the power of the one party that could have challanged the status quo. Is this what you ate saying?

Clark Cohen

Interesting ideas.

Even with “traditional” RCV counting rules, I like the idea of encouraging candidates to advise their supporters with recommended (non-binding) rankings for the other candidates. Voters would be free to take this cue directly thereby minimizing wasted votes or, alternatively, even select a different ranking order so as to “override” their candidates’ preferences should they have reason to do so. Some voters may prefer a given candidate yet have legitimate differences on who their colleagues should be.

Kristin Eberhard

Yes! In Australia the parties put out sample ballots encouraging voters to rank in a certain way. Another option could be that voters could rank all candidates if they wanted to, or they could just vote for one and let that candidate transfer their vote if they preferred that way. Then candidates could put out their preferred rankings and voters could choose what to do.

John Gear

I love that you are willing to think of an alternative and you have come up with a pretty interesting proposal that is creative indeed.

And I will think about it some more; however, my initial reaction was “Didn’t you just create a ‘candidate lists’ system rather than ‘Party List’?”

That is, instead of each party nominating candidate lists and filling them from the top down (up to the extent of the share of the votes), you have each candidate creating their own list, and if you vote for a candidate, you are really casting a vote for that candidate’s list. It’s a fascinating question, and maybe it works — but I wonder how voters will find that better.

Indeed, here in insistently independent Oregon, I anticipate an immediate response of people saying “NO, I want to be able to vote for YOU but NOT see my vote transfer to x, y, or z” — which is easily handled with RCV, but it appears that your proposal offers no way for people to prevent a transfer to an alternate candidate.

What happens when A lists the transfers to others as “B, C, D” but B doesn’t?

That is, B’s list could be “D, C, A” — kind of suggests a real disconnect between them.

These are off-the-cuff responses and subject to revision on longer thought. Bravo to you for all your hard work on this series and to Sightline for recognizing that our environmental problems will not be solved until we can address our democracy problems, and for being willing to question your own precepts.

Kristin Eberhard

Yes, you could think of these as:

* Party list = party controls the rankings = least control for voters because votes can only transfer to other members of the same party

* Delegated RCV = candidates control the rankings = slightly more control for voters because they can pick a candidate who transfers to another party

* regular RCV = voter controls the rankings = most control for voters

And you are right, probably voters would want more control. But they also want a simple, familiar ballot, so maybe voters would like thise, or maybe you are right they wouldn’t like it because they wouldn’t like the way the candidate’s transfer their votes.

sharon feola

This work is very encouraging. The concern that voters needing to know more is a drawback, is actually the point: voters do need to know more. Procedural changes may help some, but unless civic engagement and accurate information is better distributed, it will be a tough slog. Please keep up this important work.

Van Anderson

What about ranked choice voting where you don’t have to rank them if you don’t want to? In an STV/ranked choice three seat race with five candidates A, B, C, D & E, there is no reason why a person who simply “checked” A, C and D couldn’t be counted as 1/6th of a vote for each of ACD, ADC, CAD, CDA, DAC and DCA. It’s STV ranked choice voting that works as approval voting at the voter’s discretion.

Kristin Eberhard

If each candidate got the same fraction of the vote no matter their ranking, that would be like cumulative voting, which gets more proportional results than plurality, but not as good as multi-winner RCV.

Van Anderson

No, candidates still get a whole vote IF the voter chooses to rank them. However, candidates get a fractional vote IF the voter chooses not to rank. Basically, an unranked ballot in the midst of other ranked ballots is treated as 1/X votes for each of the X permutations for how those candidates could be ordered. Voters can choose to vote for one candidate like they always have, approval vote for as many or as few as they like, or they can do ranked choice. This would even allow a ranked ballot to rank two candidates the same if they so chose.

No matter how the voter decides to fill it out, you count them as ranked choice, with unranked votes counted as 1/x votes for each of the ranking permutations. The point is that it is an expansion of the ways that a voter can choose to vote, but no one is forced to vote in any way more complicated than they do now.

Greg Cusack

Both Mr. Anderson and Mr. Gear state valid points, I believe.

I honestly believe your thoughts about just having persons for their preferred candidate, while allowing candidates with fewer votes to subsequently transfer their vote totals to their preferred alternative, is — while quite creative in concept — actually might well be harder for voters to swallow than ranked voting, as — as Mr. Gear argues — it introduces a wholly new concept.

Personally, I dislike any form that would result in weighted voting — where, for instance, a voter has the right to vote for five in ranked order but chooses, instead, to vote for just one person, knowing that this person then is given 5 votes.

Instead of ranked voting, why not just allow persons to vote for, say, three from a list of candidates. This is less complicated than ranked voting and is familiar to many of us in Oregon; it has the beneficial aspect of resulting in votes for more diverse candidates, too, since if “I” prefer a, say, white female as my first choice, but then have two more votes, “I” might well then decided to deliberately broaden representation by looking for a minority candidate or two to flesh out my ballot. This seems to what happens in Oregon where such multiple votes are allowed.

Bravo, Kristen, for continuing to devote much good thought to this important idea!

Kristin Eberhard

Thanks, Greg! You are right, Bloc Voting, which many Oregon cities use, elects more women, possibly because of the very logic you lay out. But, unfortunately, it doesn’t achieve proportional results.

Lisa Richmond

This system has worked exceptionally well in Australia, my former home, for many years. It prevents the calculus that we must go through here with a third party candidate, worrying that it’s a throwaway vote. And it’s more likely to result in alignment between the overall voting public and the policies of those who are ultimately elected. This is accompanied by another Australian requirement that I think is very powerful – compulsory voting. You don’t have to vote FOR anyone, but you do have to turn in a ballot or face a fine. These two changes together would radically increase participation and investment in democratic process.

Kristin Eberhard

Indeed!

Rob Briggs

I don’t know if Kristin has addressed the issue of mandatory voting in a previous post. I like it as a strategy to prevent voter disenfranchisement, but my brother, who is Australian, says it results in a block of uninformed voters who are easily swayed by mass media, resulting in a string of clowns as prime ministers.

Ralph Nader has advocated mandatory voting but suggest we include “None of the Above” as an option for each office to fend off constitutional challenges. When “None of the Above” wins, the previous slate is ineligible and incumbents are retained until the election can be rerun. Perhaps “None of the Above” could provide a better outlet for voter anger and revulsion at available choices, than electing clowns. It would need to be accompanied by ranked-choice voting, otherwise voting for “None of the Above” would entail strategic risk.

Pete Kaslik

I’m glad you have regular articles about voting, but am frustrated by the continued emphasis on RCV. It would be nice if you found three or four potentially good voting systems and shared strengths and weaknesses of all of them, rather than only writing about the one you like best. They all have strengths and weaknesses, including RCV.

There is a group in Oregon that has attempted to address some of the problems with RCV while maintaining similar goals – achieve proportional representation but have a process that is sufficiently easy, both for the voter and for determining the winner. Determining the winner with RCV can look too mysterious to those who do not understand the mechanics of it and showing the public why a certain person won is far more difficult than with other voting methods. The organization in Oregon is called Equal Vote and can be found at http://www.equal.vote/. The voting system is called STAR – Score Then Automatic Runoff. Determining the winner is easier than RCV and is done in a way that people can understand. It is a form of range voting and theoretically, it is less subject to strategic voting than is RCV.

There are lots of theories about the benefits of each voting system. It is questionable whether all the claims are valid. Given all the locations where voting is done, it would be nice if different methods were used in different places and researchers could compare results and test the claims (e.g. negative campaigning, strategic voting). Then, perhaps, we could find a voting system that people like, trust, and results in better government.

Jameson Quinn

STAR voting is a single-winner reform, while this is a multi-winner proposal; separate issues.

Kristin Eberhard

Thanks for reading, Pete. We think the most important changes can come from a more representative legislature, which is why we write more about proportional representation methods for electing a legislature, and less about methods for electing a single office holder such as president. We support any voting system that leads to proportional results, including but not limited to multi-winner RCV. For example, I’ve written about New Zealand’s proportional method here: http://www.sightline.org/2017/06/19/this-is-how-new-zealand-fixed-its-voting-system/

STAR voting would not achieve proportional representation, but we do think it is a promising method for single-winner races like president.

You might be interested in these articles:

* Different methods for electing a multi-member legislative body: http://www.sightline.org/2017/05/18/glossary-of-methods-for-electing-legislative-bodies/

* Why we think proportional methods are better than majoritarian methods: http://www.sightline.org/2017/05/18/sightlines-guide-to-methods-for-electing-legislative-bodies/

* Different methods for electing a single-member office: http://www.sightline.org/2017/05/09/glossary-of-executive-officer-voting-systems/

* Why we think single-winner RCV is the most proven method and Equal Vote’s proposal deserves experimentation http://www.sightline.org/2017/05/09/sightlines-guide-to-voting-systems-for-electing-an-executive-officer/

llllllllllllllllllllllllllll

Score Voting systems can be adapted to multiwinner systems such as with reweighted range voting.

Proportional Representation isn’t the magic bullet people necessarily think it is. Much like the Condorcet voting method is actually worse at electing the “Condorcet Winner” than Score Voting is, many proportional representation systems introduce issues into the selection process that make them worse at obtaining practical, proportional representation of the public. It’s actually thought that a strong, democratic single-winner system performs as well if not better than a proportional system, because it’s not susceptible to issues like party ticket problems, where the electorate cannot hold candidates on the party ticket individually accountable.

RCV / Instant Runoff Voting, where there is an automatic runoff or transfer of votes, quite frankly sucks. It’s been shown mathematically to perform no better than first past the post and leads to 2-party domination. We know this because there’s several places such as Australia (which uses a mishmash of systems at different levels of government) where IRV has enforced 2-party domination for years. It’s also worth noting that most places that have introduced IRV, especially in America, have almost immediately repealed it, due to poor function as well as political reasons.

Andrew Roberts

I’m a strong supporter of ranked choice voting (RCV) and I’m glad you’re looking for ways to speed its adoption. However, I believe your alternatives do not succeed at simplifying the concept or the act of participating in a ranked choice vote.

I am hard pressed to understand how RCV could be more difficult to explain. Order the candidates by preference. If your first choice does not win, your second place vote is counted, etc. RCV does not *require* voters to rank all candidates, nor should voters be required to. (There may well be a limited number of candidates I consider viable in a race.)

Further, all forms of delegated choice in voting make me *extremely* uncomfortable, as they could result in my having contributed a vote to someone I directly oppose. Delegation treats voters as commodities to be traded and sold – particularly the supporters of minor candidates.

I urge you to re-train your focus on Instant-Runoff as the attainable derivative of true multi-winner RCV. It’s not proportional, but it eliminates strategic voting, and it puts citizens on the path to supporting proper Single Transferable Vote.

Greg Dennis

I’ve seen versions of this idea proposed before. Jameson Quinn has a similar idea baked into his “PLACE” voting scheme, although it’s obscured by a bunch of other ad hoc rules. Tim Roth’s “Pre-ranked IRV” suggestion is very similar. It would be like taking Australia’s RCV ballot, keeping the “above-the-line” option but lopping off everything below, kind of.

Ultimately, I think we need to keep an option that allows voters be voters and rank as they wish. It’s healthier to encourage voters to think, for one. If you know the rankings in advance, the system is also more prone to strategy and negative campaigning, two of the RCV selling points. Also the political opposition to this idea pretty much writes itself: someone else is going to choose how your vote is cast!

The scare-factor of a “complicated” ranked ballot seems to dissipate once voters actually use it. In the jurisdictions that use RCV, voters “get” it and like it, so let’s have more of that.

Jameson Quinn

Eberhard’s proposal is multi-member STV with delegation, where the delegated preferences are assigned post-election.

PLACE voting is at-large STV with:

* Partial delegation, where the delegated preferences are predeclared.

* Biproportionality — a guarantee of one winner per single-seat district

* An individual, local threshold of 25%, to ensure winners have some breadth of appeal and discourage excessive party-splitting

* Post-election territory assignment, so each voter can point to “their” representative from the party they most supported.

Are these rules “ad hoc”? You decide. Here’s the reasoning behind each of the differences from Kristin’s “delegated RCV”. Each one of these can be read as a criticism or potential problem I see with DRCV. Of course, I realize that complexity is an issue too, and for each of these points you could reasonably argue that the problem it fixes is not big enough to justify the additional complexity.

In my mind, the most important difference between PLACE and DRCV isn’t one of my four bullet points above, but the fact that PLACE is at-large and DRCV is restricted to multimember districts. This means DRCV offers voters less choice. Say I’m a voter focused on an issue that puts me in a minority. This could be anything — ethnicity, ideology, occupation, hobby, age, whatever. On that issue, in a state like WA (with 10 seats in the US House), there’s probably going to be just 1 candidate statewide whom I’m really excited about. In PLACE, I’m guaranteed to be able to vote for that candidate; in DRCV, there’s a 50/50 chance that I’ll be in the wrong district. The difference would be even bigger for bigger states or state legislative elections. That means, I believe, that PLACE would do even better than DRCV at increasing voter engagement, turnout, and ultimately, power.

Now I come to the 4 additional rules in PLACE:

* Partial, predeclared delegation (as opposed to full delegation with post-election assignment in DRCV). This means that in PLACE, candidates do not declare a full preference order, but just group other candidates into three general preference levels: “faction allies” who must be from the same party, those who are in the same party but aren’t faction allies, and “coalition allies” from other parties. Within each of those levels, preference order is determined by the voting outcome (descending order of direct votes); that is to say, by other ideologically-similar voters.

Keeping delegation partial as opposed to total helps ensure that party wheeler-dealers can’t insulate themselves from accountability to voters. With full delegation, a candidate who manages to convince many others to give him second preference could win with almost no votes directly from voters; with partial delegation, such an outcome is essentially impossible. So partial delegation is insurance against “smoke-filled rooms”, while still ensuring that each vote keeps as much of its original “ideological flavor” as possible.

* Biproportionality — PLACE’s guarantee that there will be one winner per district. This helps address voters’ desire to have local representation. It also makes PLACE a less-disruptive change as compared to the current FPTP system, which means a better chance to get support (or at least, avoid opposition) from incumbent politicians.

* 25% local threshold by candidate. To illustrate how this would work, look at the 2017 election in British Columbia, where they elected the 87 members of the legislative assembly. The Green party got about 17% of the votes, so their proportional share would have been about 15 seats; but under FPTP they just won 3. In PLACE, they would likely have gotten more votes, because voters would not have had to use “lesser evil” strategy; but for the sake of argument, let’s say there was a PLACE election where they got that same 17% of the vote. They only passed the 25% threshold in 10 ridings, so they would have gotten 10 seats (11.5% proportional); and the extra 5 seats worth of votes would have transferred to their “faction allies”, that is, probably to their choice of strong independent or NDP candidates. This would mean that NDP candidates would have a strong reason to court Green support. Greens would get 7 more seats than under FPTP and 5 seats of “pull” within their larger party ally.

So a fringe party with 5% would probably win no seats directly, but would still get 5% “pull” through vote transfers; they might win their first seat around 10-12%; with 17%, as in the example above, they’d get most of their proportional seats; and by the time they reached around 20-22%, they’d win a full proportional share. In every one of those cases, their supporters could vote honestly, so they’d be able to grow without a constant uphill battle against the “wasted votes” argument.

This means that the overall outcome would have 3 or 4 sizeable parties, with a smattering of single seats won by independents or smaller parties. This is a healthy balance, where the parties have to have a comprehensive platform and can’t just splinter into myopic single-issue parties (as arguably happens in Israel), but smaller groups still have a fair voice and a chance to grow (unlike in the current US system).

* After winners are decided, PLACE assigns each a multi-district territory, so that each district is in the territory of one rep per party. This strengthens the link between voters and “their” representative: even if you strongly disagree with the rep who was elected from your district, there will be a nearby rep from a party you support whose job it is to listen to you. This is different from DRCV, where the one-to-many rep-to-voter link is obscured by the mechanics of STV.

So, overall, I think DRCV is a good idea (and it was a good idea when it was proposed in 1894 in Massachusetts and called the “Gove method”), but I’ve designed PLACE to be even better. Feel free to take any of these ideas that you think are worthwhile.

John Gear

I don’t want to threadjack, but I really want to highlight Lisa’s comment above about what I have called “compulsory ballot return.”

I think that is the first, most attainable reform we can get and might very well pave the way for greater interest in better ways to vote that ballot that must be returned.

I think the arguments for compulsory ballot return are strong, especially in mail-balloting states:

1) We’re not saying you have to vote. You can vote the ballot if you want, but you do have to return it either way, with your info updated if it has changed.

You have to return your ballot because that’s the accountability check on the whole system (ensuring the bureaucracy does its job), ensuring that the state

a) Got the voter rolls right; and

b) Got you your ballot.

2) Given the not-insignificant cost of elections, printed and mailed voter guides, printed and mailed ballots, to allow people to simply ignore the ballot and refuse to return it wastes the money.

We should require that people return the ballot (voted or not) because that means all the effort and the money wasn’t wasted. Even if they don’t vote the ballot, the money was not wasted because we delivered the opportunity to exercise the franchise.

3) It ensures that the voter rolls are constantly groomed and updated, which is important to confidence in outcomes.

There is actually little to no retail voter fraud in America — but there is a fairly high concern about it (some genuine, some phony to justify disenfranchising disfavored groups). Compulsory ballot return gives us an opportunity to ensure that the voting rolls and addresses are constantly kept current and correct.

Steve Erickson

I’m (somewhat) agnostic on which system is best, but I expect people will automatically reject any system where they don’t get as many votes as the number of seats up for election. So, 3 votes to elect 5 members for a district is a non-starter. Also, I expect that people will vehemently reject having anyone other than the voter determine who gets their votes, so vote transfer according to parties or candidates choice is probably a non-starter.

Marian Beddill

My greatest concern is for integrity of the vote-tally. This might be OK for elections which are totally in ONE jurisdiction (County) – that’s how we do it now.

BUT – for positions which get elected by voters in MULTIPLE counties, that means that votes get cast in several counties, then are “transferred” to another county to be “changed” before the totals can be counted. That transfer, and the loss of control by the original jurisdiction, opens a gate for corruption – either while the sending and receiving is in process – or after the original vote-records have landed in “that other place”, where OUR staff does NOT have access to double-checking!

Say “NO” to RCV – of any variant.

Andrew Roberts

Hi Marian!

When you refer to “positions which get elected by voters in MULTIPLE counties”, are you referring to state-level positions? Or something else?

I ask because I don’t understand the “loss of control” you refer to. I presume any “delegated” or “transferred” votes would be re-counted by the same county that issued the ballots in those cases…

Thanks for clarifying!

Jameson Quinn

This is an issue of “summability”… whether winners can be found by adding up simple precinct-level totals. Regular RCV is non-summable; you need to know how to transfer each ballot. Kristen’s proposed DRCV is summable; just knowing the totals for each candidate tells you the full transfer order for each ballot. So yours is actually an important concern for RCV, but not for this DRCV proposal.

Jeremy Faludi

These are all good ideas, potentially. Hashing them out in conversation this way lacks rigor, though. As a professor of design, I suggest the Stanford / IDEO method of “human centered design” or “design thinking”: Put together 3 – 5 prototypes side by side, then getting 30 – 50 normal voters from a broad demographic (not the hyper-aware and activist group that reads these posts, much less comments) to test them, and get their feedback on the positives and negatives of each prototype. Then use that feedback to iterate the design, with another set of 3 – 5 prototypes, do another round of user testing, and keep iterating until you converge on a solution. I’d also suggest analysts go through each prototype to simulate a variety of voting scenarios to assess what unintended consequences might result from each (as some of the comments above have mentioned).

Jeff Smith

Why such a long boring name? Why not simply “ranking”? It’s what sportswriters use routinely to choose the top team in college football. If they can do it without over-complicating, how come the left can’t? Maybe do some physical labor to get too tired to drag things out?

asdf2

Ideally, I would like a candidates preference among opponents to be publicly stated, and published in the voter’s guide. However, I can easily imagine some candidates refusing to state their preferences, under the theory that simply ranking the opponents, in and of itself, runs counter to the campaign rhetoric that the opponents are all the same and that they’re the one and only savior.

Parker Friedland

If you are going to require candidates to chose who to delegate their votes to before election day, then you should show the candidates that a voter’s vote might be delegated to on the ballot.

Example:

Elijah End Corruption – I

(in small print) Leory Left > Felicia Forest > Gabriel Garcia

And then in the instructions, you could explain what the small print means to voters.

Stoney Bird

Thanks, as always, Kristin, for creative ideas.

I have to confess that the difficulty of ranking choices was a disincentive for voters. In general, the response that I’ve heard – and I’ve been talking about this with people for about ten years – is, “Oh, I like that; it’s the way I think.”

Another point to consider is that in an RCV system, no one has to rank more than one candidate. In other words, if this is the voter’s preference, the voter can treat the ballot as a non-ranking ballot. No one, so far as I know is required to put a mark beside more than one candidate.

And lastly, there may be elections where someone really only wants his or her vote to be counted in relation to one candidate. In the example, you gave, I would not have wanted my vote to be passed either to Clinton or Trump, and if Bernie had put down Hilary as his second choice, that decision would have been taken out of my hands. I imagine there are quite a few situations like this, depending on the voter.

So I’m back to conventional RCV. Long may it live – once it comes to life, that is!

Kristin Eberhard

Thanks for your years of work on this, Stoney!

Sara Wolf

This sounds a lot like Jameson Quinn’s “PLACE Voting” system, but with a few less features. PLACE lets voters opt to use their own rankings if desired.

https://medium.com/@jameson.quinn/place-voting-explained-129e65cbb625

Another option is the STAR-PR system which functions much like the Australian system but let’s voters use the 5 star ballot just like with single winner STAR Voting.

http://equal.vote

There are a number of ways to do effective proportional representation with different ballots and systems. For me it makes sense to pick the multi-winner system that uses the same ballot as our best single winner voting system- STAR Voting. That way we can elect as many or as few candidates as needed and voters can just use one consistent ballot.

Jack Santucci

Kristin, you have rediscovered what was known in 1894 as “the Gove system.” The Proportional Representation League considered this alongside “the Free List” (what we know as open-list PR) and “the Hare system” (what we know as multi-winner RCV), ultimately settling on multi-winner RCV. As you know, 24 cities later used that system, 1893-1962, with Cambridge (MA) still using it today.

As best I can tell, the anti-party faction of the PR movement did not like “Free List” for obvious reasons (party-created lists). It also did not like the “Gove system” because it thought that parties would game the nominating process — field a set of candidates with strategically delegated transfer orderings (to use your terminology).

Jameson Quinn

PLACE is designed to minimize the power of insiders to create “strategically delegated transfer orderings”, for instance to ensure a given candidate wins a seat. In PLACE, delegation is only partially to a candidate, and partially to other same-party voters, so insiders can’t pre-fix the outcome.

Kristin Eberhard

Thanks, Jack and Jameson for the history and for the clarification of how PLACE relates!

DAB

your suggestion would invite corruption with candidates and their designated alternate choices up for sale. people should be able to grasp and embrace simple RCV – we just need leadership and strong communication / improved voter user interfaces – and it can work.

Lee Mortimer

I’m late checking in and need to do better at keeping up with Sightline’s work on this issue. Kristen has offered an intriguing proposal that deserves serious consideration. A variation on Peoria IL’s “equal and even” cumulative voting or even just limited voting are also viable possibilities. But most important will be finding something that can be implemented seamlessly into a state’s existing election machinery.

Conventional ranked-choice voting, proposed for statewide elections in Maine, exemplifies the implementation challenges and potentially expensive retrofits when RCV is extended across multiple autonomous election jurisdictions and different voting equipment types. Rather than a model for other states, Maine could hand political gate-keepers the justification they seek to resist reform and stick with the status quo.

https://www.ellsworthamerican.com/maine-news/political-news/rcv-ball-back-legislatures-court/

Lee Mortimer

I’m late checking in and need to do better at keeping up with Sightline’s work on this issue. Kristen has offered an intriguing proposal that deserves serious consideration. A variation on Peoria IL’s “equal and even” cumulative voting or even just limited voting are also viable possibilities. But most important will be finding something that can work seamlessly into a state’s existing election machinery.

Conventional ranked-choice voting, proposed for statewide elections in Maine, exemplifies the implementation challenges and potentially expensive retrofits when RCV is extended across multiple autonomous election jurisdictions and different voting equipment types. Rather than a model for other states, Maine could hand political gate-keepers the justification they seek to resist reform and stick with the status quo.

https://www.ellsworthamerican.com/maine-news/political-news/rcv-ball-back-legislatures-court/

Jonah Mann

Hi Kristin,

I think I stumbled upon this same system! In my variation, the eliminated candidate in each round is the one with the most last-choice votes. https://twitter.com/jonahmann/status/1432133792831926272