Changing to a more representative electoral system makes so much sense, and yet it can be such a heavy lift. After even Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau backed away from a public promise to end first-past-the-post voting in Canada, Cascadian reformers may despair of ever prying the cold dead hands of 18th century voting off of our democracy.

But there is hope! Like Canada, the United States, and other former British colonies, the country of New Zealand once elected legislative representatives from single-member districts, with the expected majoritarian results: two-party politics and underrepresentation of women and people of color. But in the 1990s, voters opted to switch to a fairer electoral system called Mixed Member Proportional (MMP). Immediately, they saw a more diverse, representative parliament.

Why MMP worked for NZ

Mixed Member Proportional Voting was attractive to New Zealanders because it is a hybrid of the system they were used to (single-member districts where voters can elect a geographically local representative) and a system with regional or national representatives selected from party lists. Voters get two votes: one for their local representative, and one for their favorite party (read more about it in Sightline’s Glossary).

Mixed Member Proportional, with its familiar local representatives and simple ballot, could be attractive to Cascadians voters, too. The Kiwis did it, and so can we. British Columbians especially, now pledged to complete electoral reform, may be keen to hear how New Zealanders designed and passed theirs.

A failing system prompted a study

In the late 1970s and early ‘80s, three New Zealand elections produced unfair results. In 1978 and 1981, one party won more votes, but the other party won more seats in the legislature (sound familiar?). In 1984, a small right-wing third party ran just to pull votes away from the right-wing major party. In all three elections, voters were feeling fed up with the two major parties (sound familiar, United States?), and many voted for third parties. Voters grew even more infuriated when their votes had no effect: despite winning between 16 and 21 percent of the vote, third parties only won one or two out of 95 seats each year.

Finally, legislators agreed to set up a commission to look into the problem of their unfair electoral system. In 1985, the Royal Commission on the Electoral Systems studied many alternative ways of voting, including Preferential Voting, Single Non-Transferable Vote, Cumulative Voting, Limited Voting, Approval Voting, Mixed Member Proportional, Supplemental Member, and Single Transferable Vote. The following year, the Commission issued its report, unanimously recommending Mixed Member Proportional Voting for New Zealand.

Legislators took the public’s temperature

A whopping 85 percent of voters said they wanted to change the system.

Unsurprisingly, neither of the two major parties was excited by the idea of changing the electoral system that elected them. But with the Royal Commission’s recommendations echoing in the public sphere, each party tried to outdo the other by promising, during the 1990 campaign, to hold a referendum on electoral reform if it gained power. Once the National Party won the election, it tried to walk back its electoral reform promises (sound familiar, Canada?), but public pressure persisted and the parliament grudgingly agreed to hold an “indicative” (non-binding) referendum in 1992.

The referendum asked voters if they wanted to retain First-Past-the-Post voting or change the system. The party in power promised that, if a majority of voters wanted to change, it would put a binding referendum on the ballot the next year. A whopping 85 percent of voters said they wanted to change the system.

The non-binding referendum also asked which of four systems voters would choose to replace first-past-the-post, and the party in power agreed to put the top vote-getter on the ballot the next year. Voters trusted the Royal Commission: 65 percent chose Mixed Member Proportional voting.

Voters had their say

Having faced an increasingly frustrated public for more than a decade, elected officials could drag their feet no longer. They finally delivered on their promise of a national binding referendum on electoral reform. New Zealand, like Canada but unlike the United States, allows the legislature to refer important issues to the people for a vote. (Thanks to the Citizens Initiated Referendum Act of 1993, New Zealand is one of just three countries in the world that also allows citizen-initiated referenda. The other two are Switzerland and Italy.)

In 1993, a general election year in New Zealand, voters had the chance to vote on a binding national referendum on the voting system. Businesses poured money into a full-throated campaign against Mixed Member Proportional voting, with political and business leaders saying it would “bring chaos” and would be “a catastrophic disaster for democracy.” (The main opponents of proportional representation are typically the two major parties that benefit from winner-take-all, majoritarian elections, plus the interests—in this case, business—that benefit from their rule.) The pro-reform campaign had little cash but a populist wind at its back: voters disillusioned with the political class were ready for change (sound familiar, United States?). Eighty-five percent of voters came out to vote, and electoral reform won with 54 percent.

The National (right wing) party called another national referendum to get rid of Mixed Member Proportional voting in 2011, but 58 percent of voters wanted to keep it. Once given a taste of fairer voting, New Zealanders refused to go back.

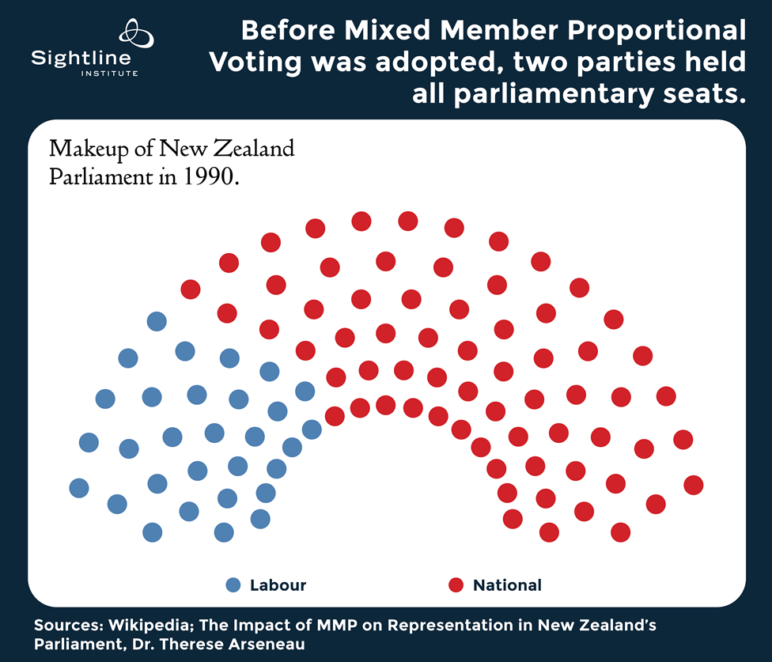

Parties proliferated

Political scientists have known for nearly a century that plurality voting in single-member districts leads to two-party domination. They even have a name for the phenomenon—Duverger’s Law. New Zealand was no exception; the Labour (left) and National (right) parties dominated the legislature.

Original Sightline Institute graphic, available under our free use policy.

As soon as the country moved away from first-past-the-post voting, Kiwis experienced a menu of party options, as well as confidence that they could vote for a smaller party without throwing their vote away. Instead of dominating nearly 100 percent of the seats, the two large parties now win around two-thirds together. The Green Party, the Maori party, the NZ First party (right-wing nationalists), and others together win around one-third of seats.

Original Sightline Institute graphic, available under our free use policy.

Maoris win more seats

Since the Maori Representation Act of 1867, Maori—the indigenous people of New Zealand, making up about 11 percent of the population—were guaranteed four seats (out of about 90) in the Parliament. Since 1975, Maori people can choose whether to enroll to vote for the Maori seats or for the general seats. (Prior to that, they could only vote for the designated Maori seats.) Some argued that the designated Maori seats should be eliminated when New Zealand moved to proportional voting, but the Maori managed to retain them. All voters now cast one vote for their district representative and one for their preferred party, meaning voters on the Maori rolls could cast a vote for their Maori district representative and one for the Maori Party, and voters on the general rolls could cast one vote for their district representative and one for their party. Proportional voting has helped them increase their share of Parliamentary seats from 4 or 5 percent before proportional voting to between 13 and 19 percent since.

Original Sightline Institute graphic, available under our free use policy.

Women win more seats and more leadership positions

Prior to proportional voting, women won between one and 16 percent of seats, except for a high of 21 percent in 1993, the year that voters approved a change to the electoral system and adopted citizen-led initiatives. Since New Zealand instituted proportional voting, women have consistently made up about one-third of Parliament. Much of women’s gains come from the Party List seats—more than 40 percent of representatives elected from party lists are women, compared with just 15 percent from the single-member districts. One of the reasons for the discrepancy is that small, left-leaning parties tend to put women in their top spots.

Original Sightline Institute graphic, available under our free use policy.

While one-third is not gender parity, it may have brought women to the critical mass where they start to have more power. Indeed, women have expanded their role on the leadership Cabinet from zero in most years before the referendum to seven, eight, or nine of 27 in recent years.

Original Sightline Institute graphic, available under our free use policy.

What Cascadia can learn

Change is hard, especially for those who benefit from the status quo, such as parties that are able to win more seats than their votes because of a flawed electoral system. Having a trusted commission study the problem can help instill confidence that a different system could work better.

British Columbia has already conducted a citizen-led study that recommended Single Transferable Vote. Oregon or Washington could similarly assemble a group of diverse citizens to carefully consider options for the states’ electoral methods and make recommendations.

Finally, because legislators are reluctant to change the system that elected them, the path to electoral reform is likely through a referendum or initiative. Once implemented, though, voters will see both more power in their vote and more diverse representation in their legislature—and they may never look back.

Kelly Gerling

Very good article Kristin. Brilliant!

One thing I would add, is simply to note that in 2011, 15 years after the first MMP Parliament assembled in 1996, there was another national referendum with two questions, enabling citizens of New Zealand to decide whether to go back to the older system, whether to keep the new system, or whether to change to a number of other possible multiparty systems. This process of a sovereign people of a sovereign country deciding to seize the inherent right to make such decisions has a level of importance for Americans that cannot be overestimated.

Exercising our popular sovereignty through citizen-led initiative and referendum is a necessary (but not sufficient) prerequisite for changing the system we have in America either at the state level or at the national level.

Key questions include:

What are the elements of a campaign for Washington state to get initiative and referendum for making constitutional amendments to create a new, modern multiparty legislature or legislatures?

How do we as a nation, both psychologically and politically, bring about our first ever national referendum initiated by American citizens to amend or replace our 1787 Constitution, as New Zealand changed theirs?

Ronald Shenberger

Excellent article. It was successful in relatively small political systems. I wonder what the possibility would be in a country the size of U.S. Perhaps it would be successful at the state level rather then national at this time. I also wonder about the influence of corporate money in the political process. Need to band non citizen money in the political process.

Erik Moeller

Ronald,

I think you’re right that it would be more likely to succeed at the state level in the US first. That would also be a good way for the US public to become familiar with different systems, and for local parties to grow in strength (and turn into more powerful lobbyists for change).

There’s a pretty solid proposal for how this could work in California, for example:

http://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1001&context=llr

In my home state of Oregon, the state constitution makes explicit allowances for proportional representation ( see https://ballotpedia.org/Article_II,_Oregon_Constitution ) thanks to a 1908 amendment. What’s lacking is popular momentum in favor of changing the system — the two main parties have no interest in competition from smaller parties, so this has to come from bottom-up mobilization.

Ken Cousins

First off, *every* system can be gamed. Second, New Zealand’s shift to MMP was a strategy of the National Party to “lock in” the country’s neoliberal reforms, since no party would be able to overturn the reforms on their own.

New Zealand’s reforms were more extreme than Chile’s.

This is a *wildly* naive interpretation of Kiwi politics and political history. I am appalled – Sightline is capable of so much more. So disappointing.

Kristin Eberhard

Hi Ken – Records indicate the National Party was not enthusiastic about the reform, and indeed it lost ground in parliament. It would be an odd strategy for a party to advocate for a reform that will cause it lose power in the future in an attempt to preserve its past actions.

But I’d be interested to know more—can you point me to evidence about this theory?

Eddy Saul

As a Kiwi I’d like to point out that Maori had the right to opt to vote on either the General or the Maori electoral roll, I had that choice. The inference that there was an apartheid system for votes operating is not justified.

Eddy

Kristin Eberhard

Thanks Eddy – I added a sentence clarifying that, after the Labour Party introduced the “Maori electoral option” in 1975, voters had the choice. Prior to that, Maori were only allowed to enroll in the Maori rolls.

Parker Friedland

I am not the biggest fan of MMP, because while proportional voting methods are the most resistant voting methods to strategic voting due to their proportional nature, this is not the case with MMP. While every type of mixed member proportional systems is parented to have massive flaws in comparison to other voting systems, at least one type of MMP is superior to the other.

There are two main types of MMP:

MMP type 1 – you vote for 1 candidate and accountability seats are then awarded to make the seats each party receives more proportionate to the amount of votes that were cased to members of those parties.

MMP type 2 (the more stupid and commonly used version) – you vote for 1 candidate as well as your favorite party and accountability seats are then awarded to make the seats each party receives more proportionate to the amount of voters that identified each party as their favorite. However this form of Mixed Member “Proportional” Voting is NOT even proportional due to strategic voting. The way Germany attempts to mitigate the damage of this disastrous flaw in MMP2 is by baring smaller parties that don’t get a certain threshold of the vote.

Let’s say that there are three parties: Red, Green, and Blue (very similar to green.)

Election 1 (with honest voters):

50 Red Voters : vote for Red candidates and Red Party

50 Blue Voters : vote for Blue Candidates and Blue Party

Local Seat Results : 20 Red Candidates, 30 Blue Candidates, 0 Green Candidates

Accountability Seat Results: 30 Red Candidates, 20 Blue Candidates, 0 Green Candidates

Total Seat Results : 50 Red Candidates, 50 Blue Candidates, 0 Green Candidates

Red Coalition: 50 Seats

Blue Green Coalition: 50 Seats

Election 2 (with dishonest Blue voters):

50 Red Voters : vote for Red candidates and Red Party

50 Blue Voters : vote for Blue candidates and Green Party

Local Seat Results : 20 Red Candidates, 30 Blue Candidates, 0 Green Candidates

Accountability Seat Results: 15 Red Candidates, 0 Blue Candidate, 35 Green Candidates

Total Seat Results : 35 Red Candidates, 30 Blue Candidates, 35 Green Candidates

Red Coalition : 35 Seats

Blue Green Coalition : 65 Seats!!!!!! LANDSLIDE!!!!!!

I think it’s about time that we call this form of MMP2 what it really is : MMNP (Mixed Member Non Proportional)

Parker Friedland

Typo, at the top, I meant guaranteed, not parented.

Alan Zundel

Parker, both major parties could use the same tactic of voting for a minor party partner, balancing out any advantage. It would also have the effect of increasing minor party seats to compensate for their disadvantage in the candidate elections.

MMP2 in my view would have a much easier time passing politically because it would not take away seats from the candidate elections or increase the size of the legislature in an unpredictable way.

Parker Friedland

Yea, that is true, however when both parties deploy this tactic, MMP2 (what I refer to as MMNP) becomes only half proportional.

Let’s say each political party at the local level has an identical clone party at the proportional level for strategic purposes. In the example I listed above, the Green Party behaves as the Blue Party’s clone party. We shall refer to the original Blue party as Blue1 and the Green (Blue clone) party as Blue2. We shall refer to the local level Red party as Red1 and Red’s proportional level Red party as Red2.

In the original example I gave, half of the seats were elected locally and half are elected nationally. So if both the Blue and Red voters are 100% strategic, all 50 of the locally elected seats will be elected using the awful FPTP method and the other 50 proportional seats will be elected using party list proportionality.

However each party at the proportional level has an identical but legally different party at the local level, thus the two levels act independently of each other. Thus MMP2 devolves into voting for half of the legislature with FPTP districts and the other half with party list PR.

Thus any advocates of MMP2 might as well advocate for electing just half of their legislature with party list proportionality and save themselves the hassle of dealing with the many forms of strategic voting that come with all MMP systems to begin with. However I wouldn’t call a legislative body proportional if only half of it were elected with a proportional method and nether should you.

G.H. Oliver

Friedland, that is called a Freudian Slip and not just a “typo.” Ha.

Are we concerned about coalitions forming with third parties?

Parker Friedland

No. That is not the problem. The problem is that when 100% of voters and political parties are strategic and each party has an identical but legally different clone party. When every voter votes for a party specifically for district elections, and a different party specifically for the added seats to create proportionality, the district seats and the proportional seats become 100% independent of each other. That means that under this system, when only half of the seats are seats to create proportionality, and half are seats from districts, the resulting legislature is only half proportional.

Example of what would happen as a result of MMP2 and strategic voters:

10% of voters – Democrat for local district, Green Party

25% of voters – Democrat for local district, Draft Bernie Party

15% of voters – Democrat for local district, Stronger Together Party

15% of voters – Republican for local district, Libertarian Party

25% of voters – Republican for local district, Make America Great Again Party

10% of voters – Republican for local district, Tea Party

District Elections :

Democratic Party – 0 Seats

Green Party – 22 Seats

Draft Bernie Party – 54 Seats

Stronger Together Party – 33 Seats

Libertarian Party – 33 Seats

Make America Great Again Party – 54 Seats

Tea Party – 22 Seats

Republican Party – 120 Seats

Seats to make the legislature “proportional” :

Democratic Party – 0 Seats

Green Party – 0 Seats

Draft Bernie Party – 0 Seats

Stronger Together Party – 0 Seats

Libertarian Party – 0 Seats

Make America Great Again Party – 0 Seats

Tea Party – 0 Seats

Republican Party – 120 Seats

The end result is a legislature that is only half party list proportional and half FPTP.

Parker Friedland

Wait. I messed up the thing above. Corrected version:

District Elections :

Democratic Party – 97 Seats

Green Party – 0 Seats

Draft Bernie Party – 0 Seats

Stronger Together Party – 0 Seats

Libertarian Party – 0 Seats

Make America Great Again Party – 0 Seats

Tea Party – 0 Seats

Republican Party – 120 Seats

Seats to make the legislature “proportional” :

Democratic Party – 0 Seats

Green Party – 22 Seats

Draft Bernie Party – 54 Seats

Stronger Together Party – 33 Seats

Libertarian Party – 33 Seats

Make America Great Again Party – 54 Seats

Tea Party – 22 Seats

Republican Party – 0 Seats

MMP2 will look like something similar to this when voters are 100% strategic where the results are half proportional. If your end goal is proportionality, why would you settle for half proportionality. And if you don’t mind half proportionality, then why not elect the district seats and added seats separately to avoid the many ways all MMP systems can be strategically gained.

Alan Zundel

Half party list proportional and half FPTP would be more proportional than just FPTP, to state the obvious. Full proportional won’t fly in the U.S. due to loss of candidate-district ties and its just too big a change. That’s my opinion, for what its worth.

Parker Friedland

But if you just want half-proportionality, then just argue half proportionality. Then you don’t have to worry about “grand theft political” (which I will explain) or party overloads.

“grand theft political” – when candidates from an opposing ideology runs in your party to steal seats.

Example – Original Results

District Elections :

Democratic Party – 97 Seats

Green Party – 0 Seats

Draft Bernie Party – 0 Seats

Stronger Together Party – 0 Seats

Libertarian Party – 0 Seats

Make America Great Again Party – 0 Seats

Tea Party – 0 Seats

Republican Party – 120 Seats

Seats to make the legislature “proportional” :

Democratic Party – 0 Seats

Green Party – 22 Seats

Draft Bernie Party – 54 Seats

Stronger Together Party – 33 Seats

Libertarian Party – 33 Seats

Make America Great Again Party – 54 Seats

Tea Party – 22 Seats

Republican Party – 0 Seats

Now let’s say that some right wing candidates (surprisingly) got clever and ran in your Draft Bernie Party at the local level in the deep south and got their supporters to vote for them. These candidates and their voters are attempting to try the

“grand theft political” strategy in order to rob the Draft Bernie Party.

District Elections :

Democratic Party – 97 Seats

Green Party – 0 Seats

Draft Bernie Party – 50 Seats (+50 Fake Draft Bernie Party Seats)

Stronger Together Party – 0 Seats

Libertarian Party – 0 Seats

Make America Great Again Party – 0 Seats

Tea Party – 0 Seats

Republican Party – 70 Seats (-50 Seats)

Seats to make the legislature “proportional” :

Democratic Party – 0 Seats

Green Party – 27 Seats (+5 Seats)

Draft Bernie Party – 17 Seats (-37 Seats)

Stronger Together Party – 40 (+7 Seats)

Libertarian Party – 40 Seats (+7 Seats)

Make America Great Again Party – 67 Seats (+13 Seats)

Tea Party – 27 Seats (+5 Seats)

Republican Party – 0 Seats

Look at what happened!

Every voter who voted for a left leaning candidate last election still voted for a left leaning candidate this election and every voter who voted for a right leaning candidate last election still voted for a right leaning candidate this election. And everyone also voted for the exact same party they voted for last time as well.

However despite this fact, the left lost 25 Seats in congress and the right gained 25 seats in congress. So congress was only half proportional to begin with and now it is even less proportional. And while overall Draft Bernie Party now has 67 Seats, only 17 of those individuals actually represent the Draft Bernie Party.

In Reality though this wouldn’t happen. If Draft Bernie voters were strategic and knew what was going on ahead of time, they would give their party vote to the Green Party in order to counteract the right wing tactics. However the Draft Bernie Party would still be destroyed in the process.

Unfortunately this strategy is still effective enough to non-strategic voters that Germany requires the political parties themselves to chose which candidate from their party are allowed to run in each district. In this way, local races in Germany are like assigned seating in kindergarten.

To make matters worse, Germany requires any political party to get 5% of the vote to even win any seats at all. The idea behind this is that smaller parties are more vulnerable to tactical voting and Germany hasn’t 100% devolved into half-proportional elections yet, so they can still maintain a bit more then half proportionality if there are a small number of parties. However the result of this is that Germany is forever locked into a 5 party system where political parties get to assign politicians to districts like in kindergarten: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bundestag

Parker Friedland

Also, the local district seats in New Zealand’s parliament are slowly devolving back into a two party system (probably because voters are beginning to take advantage of the strategies a talked about). Here, look at New Zealand’s most recent parliament: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:New_Zealand_Parliament_seats,_2017.svg

Doug Wright

Nice article Kirsten.

As you wrote, “Changing to a more representative system makes so much sense….”

The main drawback of New Zealand’s Mixed Member Proportional Voting system is the Party List proportional representation voting component. The Party List ensures 100% of voters fail to directly elect candidates of choice. As a result, the Party List dilutes and reduces the total proportion of legislative assembly members that are directly elected as representatives of choice.

To be more representative; electoral reform should enable large majorities of voters to directly elect party candidates of choice, not just parties of choice.

Proportional representation electoral systems have been developed to enable close to 100% of voters to directly elect candidates of choice. This enables voters to exert far more control over representatives they elect than the Mixed Member Proportional Voting system of New Zealand.

Additional information is available at Election Districts Voting. The website covers new first-past-the-post, alternative vote (also known as instant-runoff voting or ranked-choice voting) and single transferable vote proportional representation electoral systems. These systems strengthen voting power, create a strong connection between voters and representatives, provide more diverse representation and improve the quality of representative government.

Sara Wolf

Super interesting. Thanks for the history! With the US being such a large country our voting system has a few unique considerations to be factored in but I see a huge benefit to electing a statewide legislature by a proportional representation method, for starters. What if the State Reps were elected by local district and then the State Senate was proportional? That could be a balance of local and then also demographic representation.

My main concerns with MMP are the party aspect which is problematic because FPTP has already created such non-representative and internally fractured parties. I would much prefer to vote on candidates, not nebulous and controversial party platforms.

Second, I just don’t think that vote-for-one candidate systems are expressive enough. What do you do if you support multiple candidates? Forcing voters to choose sets us up for skewed and non-representative outcomes. It also doesn’t let us show degree of support and the problems are magnified the more candidates are in the race.

I’d love to see more attention given to proportional representation using a 5 Star ballot and then tabulating using a form of Re-weighted Range Voting or Star Voting-PR. This would pair well with the most accurate and representative single winner method and give voters one user-friendly package that effectively covers all types of elections that might be needed from single winner, multi-winner, and fully proportional. For single winner elections Star Voting (SRV) is the clear best option overall and the benefits translate perfectly to PR. http://www.equal.vote

Hilda Highground

A very naive article based on the presupposition that diversity and representativeness are inherently good. The most important virtue of a democracy is the ability to decisively remove a corrupt government peacefully. Proportional representation makes that more difficult.

It also places immense power into the hands of party leaders. And there is nothing inherently wrong with a two party system like the US has – the current toxic political environment is a function of many things, but the two party dynamic can’t account for much.

Alan Zundel

Representativeness is not inherently good? I would see that as the main point of electing representatives. If a government represents the public, it won’t be corrupt. I don’t see how PR makes removing a corrupt gov’t more difficult, but in any event MMP is not pure PR. MMP does not place that kind of power in party leaders either.

And I would say lots of problems in the US political system are traceable to the two party system. People feeling unrepresented. Easier for big money to buy two parties than eight. Polarization. Policy seesaws. Donald Trump.

Alan Zundel

http://www.rcvoregon.org/mixed_member_elections_for_the_oregon_legislature

Richard Lung

Commenters seem to know how bad MMP is, despite this starry-eyed article. The NZ Royal Commission took their cue from the UK Labour Plant report. Labour is an anything-but-STV party, because of the “intra-party competition” and high turn-over of MPs in Irish elections. The democratic audacity of STV in-built primaries alarmed the Preliminary Plant report, also noting that AMS/MMP did not so threaten their incumbency.

So much is this the case that the Richard report on the Welsh Assembly denounced AMS (aka MMP) as denying the voters the fundamental right to reject candidates.

MMP is a doubly safe-seat system of dual candidature. Even FPTP is only a singly safe-seat system of local monopoly representation.

As a previous commenter exemplified, MMP is also potentially a winner-takes-all majoritarian system, as the dominant parties in single member districts can put out “fake parties” to win more seats from party lists.

The real mischief of this gaming the system is not that politicians might deliberately do this, as in the case of Berlusconi’s party creating an extra “fake party”, Forza Italia, for the list vote, they were not proportionally justified in having. The real mischief is that MMP puts any independent party in temptation to effectively become a fake party, to satisfy their hunger for office.

Comments cannot do anything like justice to the monumental mess-up of this system, whose FPTP component is nullified by its second-chance list seats for candidates. And whose party proportional component is undone by its entrenching the larger parties in the fewer and therefore even more disproportionate single member constituencies.

Frequently MMP supporters closed minds are as closed as their party lists, and their claims for MMP as unjustified as the claims that so-called “Open” lists are open. And they often find fault with critics of MMP rather than admit what a dead-end for democracy and science, that MMP really is.

By the way, I wholly support the BC Citizens Assembly recommendation of the Single Transferable Vote, whose explanatory power to the people is as great, as that of MMP is dismal.

Richard Lung. “Democracy Science.”

Nico

Great article, however these images were very misleading for myself to read (I’m from NZ). The Labour Party’s colour is red, and National is Blue, these pictures just look so silly to me.

Kristin Eberhard

Thanks for reading! Yes, I changed the colors to speak to my American audience, where we associate blue with the more progressive party and red with conservative.