[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Editor’s note, 5/10/19: An earlier version of this article featured maps of single-family zones in Seattle from 1923-2014 that had inaccurate information. The maps have been removed. We will publish corrected maps in the near future and link to them here.

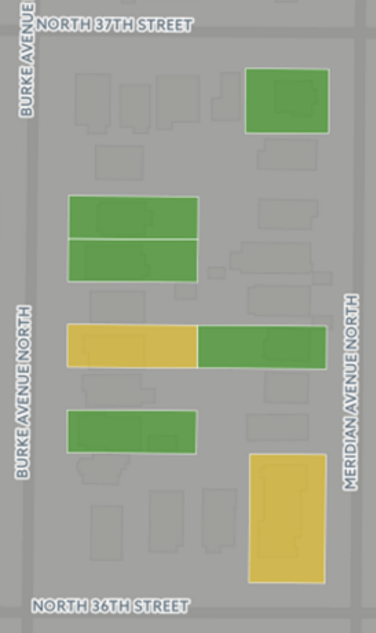

This is the story of a single city block in Seattle’s Wallingford neighborhood. It’s a picturesque, tree-lined rectangle, located just north of Gasworks Park. It’s bordered by North 36th and 37th Streets and Burke and Meridian Avenues.

[sightline-embed]

The city has zoned the block single-family, allowing only one detached home per lot (plus accessory dwelling units, should residents choose to build them). Under this zoning, this little block should only be able to host 24 households–one per parcel. Yet in reality, the block provides shelter for 37 households, more than one-and-a-half times its zoned capacity.

Under today’s zoning code, these thirteen additional households, likely including over 27 Seattleites, would have had to compete for housing elsewhere in the city or leave Seattle altogether, perhaps taking on longer commutes to hold down their jobs. Instead, members of these households can walk to Gasworks Park and the Burke-Gilman Trail, two of Seattle’s best-loved public spaces. They live within one block of an Italian restaurant, a salon, a church, and a local chocolatier, within two blocks of a bus stop, and within three blocks of a grocery store. Not only can they patronize these local businesses, supporting their neighborhood’s unique flavor and charm, they can do so on foot, allowing them to shrink their carbon footprint.

To what do these 13 households owe their housing in this coveted neighborhood?

To Seattle’s zoning history. The block includes 5 duplexes, a quadplex, and a 6-unit apartment building, which together host these 13 additional households.

Here’s the catch, though: none of these structures could be built today. They are remnants of the neighborhood’s more flexible zoning history, which permitted a greater diversity of housing types, making room for more people to enjoy and bring life to this corner of Seattle.

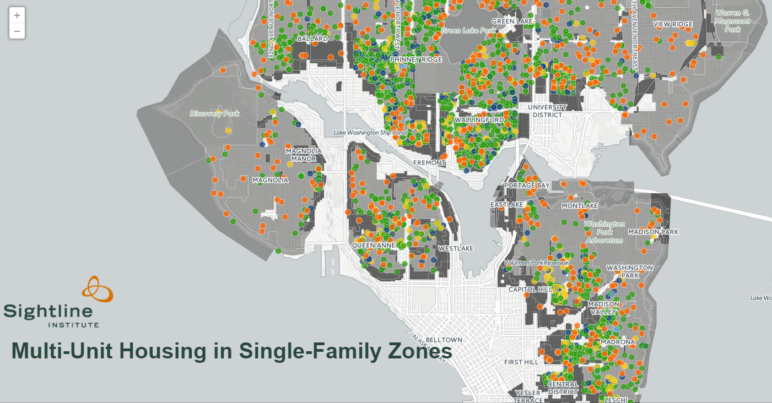

In December, Sightline published a map (also linked at the head of this article) displaying all of the multi-unit homes in Seattle’s single-family neighborhoods. These almost 10,000 homes include ‘plexes—duplexes, triplexes, and quadplexes—townhomes, and accessory dwelling units (ADUs), and they provide housing for about an additional 12,000 people who call the Emerald City home. Had these multi-family units not existed, these 12,000-odd people would be looking for housing elsewhere in the area, bidding up prices in an already expensive city.

Yet all but the ADUs are now illegal to build in single-family zones. As I pointed out in our accompanying article, most of the units on the map are relics of Seattle’s zoning past. In this article, I’ll trace the zoning history that made these homes possible. Multi-family homes already deeply ingrained in Seattle’s neighborhoods. But the irony of Seattle’s zoning history is that its zoning code has clamped down on the city’s housing capacity even while housing demand has skyrocketed.

[button link='{“url”:”http://www.sightline.org/2016/12/12/seattles-single-family-neighborhoods-already-include-thousands-of-duplexes/”,”title”:”Related: Seattle|apos;s single-family neighborhoods already include thousands of duplexes.”,”target”:”1″}’ color=”green” is_full_width=”1″]

Why does this all matter? Because Seattle now has the chance to once again open its single-family zones to a broader mix of housing, including duplexes and triplexes. Returning the city to its more flexible zoning past could provide housing for thousands of additional families.

Memoir of a city block

The Wallingford block highlighted above—which is typical of its neighborhood, not an exception—hosted all but one of its multi-family structures prior to 1920. This reflects a larger pattern: Seattleites built over half of the three-thousand-odd ‘plexes currently standing in the city’s single-family zones prior to 1923. That was the year Seattle published its first zoning ordinance, placing the first of a long succession of restrictions on homebuilding across the city.

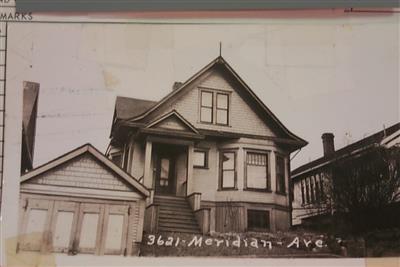

Here are early images of some of the street’s multi-family units from the King County Assessor’s archives:

This first zoning code was relatively simple, containing just six zoning types, only two of which were residential. It designated between a quarter and a third of the city as “first residence districts.” First residence districts were the predecessor to today’s single-family zone; within these districts, builders could only construct single-family, detached homes, and a few non-residential buildings (like schools, churches, and art galleries). City planners grandfathered existing ‘plexes into these newly designated areas, but prohibited new buildings of these types. The majority of first residence districts fell closer to the city’s north and south edges. (At the time, Seattle’s northern boundary was North 85th Street; it’s since moved north to 145th Street.)

[list_signup_button button_text=”Like what you|apos;re reading? Get our latest housing-related research straight to your inbox.” selected_lists='{“Housing Shortage Solutions”:”Housing Shortage Solutions”}’ align=”center”]

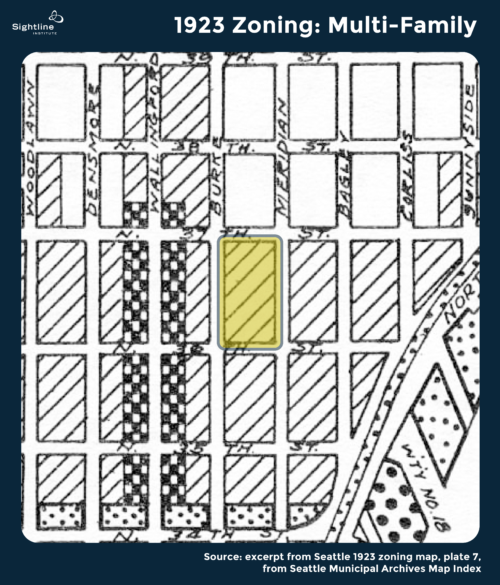

Our Wallingford block fell into the other residential zone category defined in this first zoning ordinance—the “second residence district.” This zone type covered less than a quarter of the city, but was much more flexible than the first residence district. Property owners could develop any type of residential dwelling in these areas, from single-family homes to duplexes to apartment buildings. Planners located almost all of this zoning type closer to the city’s downtown core. As a result, neighborhoods closer to the city center today have a much broader diversity of housing choices than neighborhoods located farther from downtown.

Here’s an image of our block from the city’s first zoning maps. The maps indicated second residence districts with diagonal hash marks.

In 1956, the block saw the construction of its last multi-family housing structure, the six-unit apartment building at the corner of 36th and Meridian. This building snuck in just under the wire, as the following year the city downzoned this block as part of its first major zoning code overhaul.

The 1957 zoning ordinance included a new set of zoning classifications, downzoned many second residence districts, and designated an even greater percentage of the city as exclusively available to single-family, detached homes.

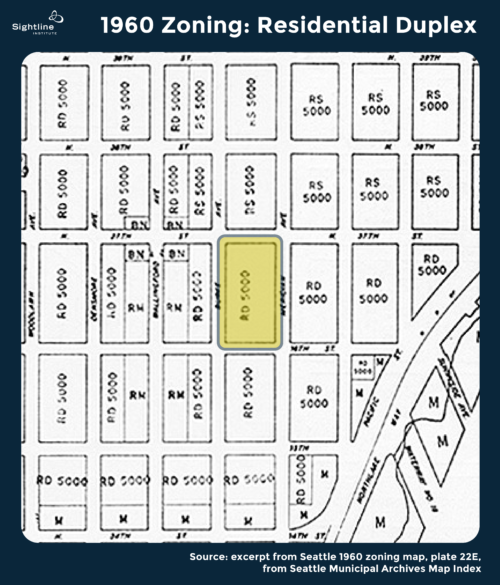

Our Wallingford block was a part of this city-wide downzoning process and was rezoned into a new zoning type called “residential duplex.” Duplex zones were a half-step between first and second residence zones, as they permitted duplexes and some triplexes, but not other multi-family housing, like small apartment buildings.

Later zoning ordinances further downzoned most of these duplex zones, until the code completely did away with the evolved version of this zoning type, the lowrise duplex/triplex zone, in 2011. Here is an image of our Wallingford block wearing its new residential duplex zone (RD) label in the city’s 1960 zoning maps.

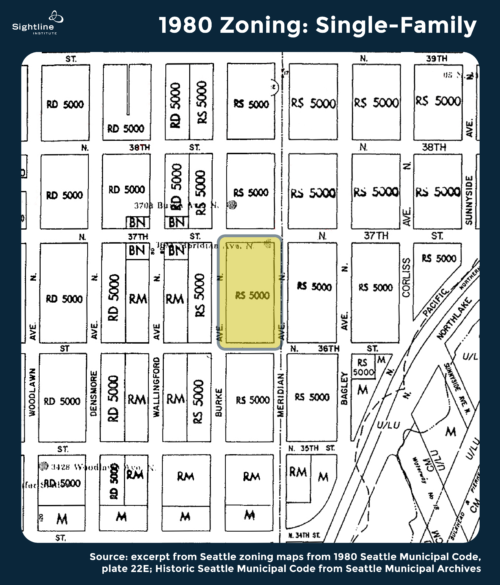

The story ends in 1980 when our block received its final downzone, this time to its current zoning classification: single-family. This corresponded with the city council’s second major facelift to the city’s zoning. That year, the council updated the requirements for many of the zoning types and continued to expand the share of the city limited to single-family houses.

Since 1980, the block’s housing capacity has remained fixed, despite a nearly 40 percent increase in the city’s population. Though the city permits the construction of ADUs in the neighborhood, none of the block’s residents has chosen to build one yet. They’ve likely been discouraged by the complex regulations that govern ADU construction in Seattle. The housing story of this single block mirrors Seattle’s broader housing story, in which ever more complicated zoning regulations have progressively strangled housing choices and capacity for the increasing number of families and individuals who need them more than ever.

The 90-year creep of single-family zoning across Seattle

The Emerald City has witnessed a slow but steady creep of single-family zoning across its landscape. In 1923, single-family zoning covered roughly one-third of the (geographically smaller) city. Today, this zoning type consumes more than half of Seattle. As the city council downzoned larger and larger tracts of Seattle to single-family status, it grandfathered existing multi-family buildings into these areas but prohibited the construction of any more of them.

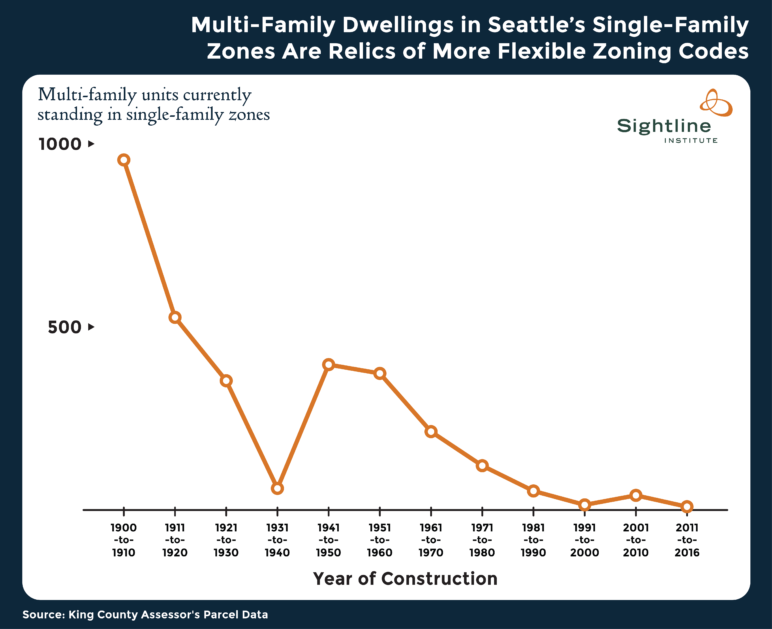

The graph below sorts the multi-family dwellings currently standing in Seattle’s single-family zones, excluding ADUs, by the year in which they were built. With the exception of a spike during World War II, the number of multi-family dwellings standing today in single-family zones that date from each decade drops over time, as zoning became ever more restrictive across the city. These numbers understate how many were built, especially in earlier decades, because they ignore ‘plexes that were subsequently torn down. Every one torn down had to be replaced with the only thing legal: a single-family house.

ADUs: More homes… if less red tape

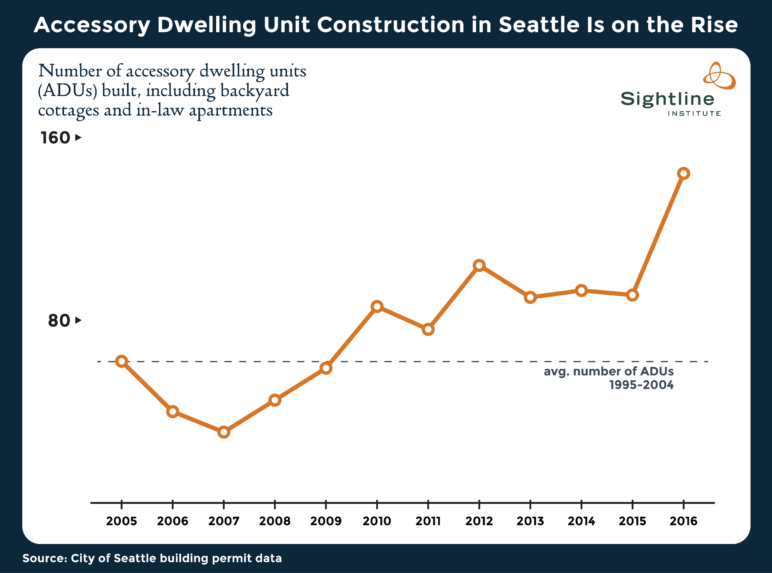

Accessory dwelling units (ADUs) are the only additional dwelling unit the city currently permits on lots in single-family zones. The city permits the construction of ADUs inside or alongside detached, single-family homes. The city legalized attached ADUs in 1994 and brought detached ones (DADUs) into the fold in 2009. Since 1995, homeowners have added nearly 1,500 of them to the city’s housing supply. Over this two-decade period, building of ADUs has trended upward.

Still, regulatory barriers thwart much ADU construction, and growth in this type of multi-family dwelling has been glacial. Though the 1,500 additional homes property owners have added to the city through ADU construction have brought a range of benefits to those lucky enough to call them home, barely one percent of the city’s single-family lots have a secondary unit, lagging far behind Vancouver, BC, where more than a third of single-family homes make space for another tenant.

The real promise of reopening single-family zones

Seattle’s Housing Affordability and Livability Agenda (HALA) recommends reopening Seattle’s single-family zones to a broader mix of housing, including duplexes, triplexes, and rowhouses. Some Seattle residents have viewed this recommendation as a threat to the character of Seattle’s single-family neighborhoods. Yet, as we’ve seen in the history of a typical block in the Wallingford neighborhood, duplexes, triplexes, and other multi-family homes have been a part of many of Seattle’s single-family neighborhoods for much longer than some of their single-family homes—and far longer than most residents. Indeed, the city grew up with these housing choices.

The HALA report also recommends increasing the supply of ADUs and DADUs by removing code barriers that hinder construction of these units. Though ADU construction has been gradually on the rise over the last two decades, Seattle lags far behind other Cascadian cities in incorporating this housing type into its landscape. As we covered in a previous article, ADUs allowed many neighborhoods in Vancouver, BC, to achieve a density at which neighborhood stores could thrive, more transit options became viable, and car ownership became less necessary—all while preserving the architectural feel of the neighborhood. Take a look at the street view images of some of the ADUs on the map and you’ll see the same: the ADUs are hard to see from the street, yet each one has given another person or family access to a neighborhood blooming with potential.

Reopening some of Seattle’s single-family zoned land to these housing choices would offer people more options when looking for housing, making this Wallingford block a model for the future of the Emerald City. As in this corner of the city, duplexes, triplexes, and ADUs could offer residents the ability to choose a smaller space and still enjoy the benefits of a walkable neighborhood. They could offer more families access to the city’s top schools and parks, most of which are in exclusive, single-family neighborhoods. These housing options could also grow the vibrancy of many neighborhoods, permitting them to house enough residents to support local businesses, restaurants, and frequent transit. Housing choices benefit not just those they shelter by meeting a range of housing needs, but also the neighborhoods they become a part of, bringing diversity and vibrancy to their communities.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

Thanks to map maker Jeffrey Linn of Spatialities for his tireless work to make this map as accurate as possible.

Also thank you to CartoDB for providing Sightline with a grant to use its map hosting services.

Note 3/9/17: The four maps showing the growth of single-family zoning in Seattle since 1923 show the overarching story of this zoning type in the Emerald City, but may not be precise down to the city-block level. We are currently working on a block-by-block review of the city’s zoning history. Stay tuned for publication of this piece later this year.”

Comments are closed.