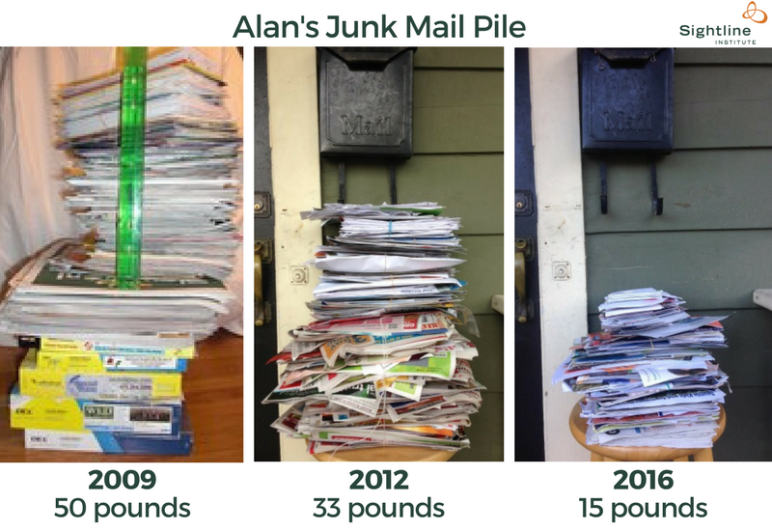

Fifteen pounds.

Thanks to Catalog Choice, Seattle’s phone book opt-out, and vigilance against Red Plum and other advertisers, I have purged and pinched my annual junk mail tally down to 15 pounds. Last time I weighed in, in 2013, it was 26 pounds; in 2012, it was 33 pounds (half of it from the hated Red Plum); and in 2009, the pile tipped the scale at 50 pounds. Just the phone books made up 15 pounds of it.

Time to declare victory? Nope. I am starting a new pile in January, and I’m hoping the deluge will wane to single digits during 2017.

Original Sightline Institute graphic, available under our free use policy.

Junk mail ads are 96 percent waste

Junk mail is not among Cascadia’s top environmental priorities, but it’s something, and it ought to be among the easiest to solve.

For one thing, junk mailers themselves crave better targeted mailing lists. If they could only mail catalogs and brochures and coupons to people inclined to buy, they’d make a lot more money. US companies spend about $46 billion mailing ads every year, but typically fewer than 4 percent of recipients respond. Junk mailers, that means, throw away more than $44 billion a year. The trouble is, they do not know which recipients are inclined to buy at any given time. By purging myself from the lists of merchants I’ll never buy from, I’m doing them a favor, saving myself time, and sparing the earth some grief.

The grief to the earth does add up. Direct mail advertising makes up approximately 2 percent of US municipal solid waste: in Seattle alone, it’s 18,000 tons of paper annually, and it boosts city waste hauling costs by about $400,000 a year. The larger environmental costs are in production, not disposal, of all that paper. A lot of forests fall, oil burns, and industrial inks are synthesized to print and deliver almost 80 billion unsolicited sales pitches per year to mail boxes in the United States.

The personal aggravation accumulates too. I shouldn’t have to spend time emailing credit card hawkers or warning every retailer from whom I request home delivery not to add me to a mailing list. I should just be able to opt out, once and for all, from unsolicited advertising carried by federal agents onto my property. As I’ve been saying, Cascadian jurisdictions should enact a Do Not Mail Registry.

Sadly, that doesn’t appear likely to happen soon.

Junk mail quantities have been dropping steadily

What is happening is that junk mail is waning on its own. Many people are, like me, fed up with it. Marketers are finding other ways to reach customers. And, above all, the internet is killing it.

Below is a figure of the total number of pieces of mail of all kinds handled by the US Postal Service each year since 1950. (Unfortunately, Cascadia-specific data are unavailable, so national numbers are the best we have to understand the trends.) Advertising mail drove the explosion of USPS deliveries starting in the late 1970s. After peaking in 2006, mail volume has fallen back to 1987 levels. The volume of mail has fallen 28 percent in the last 10 years, even as population and the economy have grown. The Great Recession likely triggered the collapse of ad mail, but other forces, mostly the internet, have sustained the decline. Canadian mail is declining too. It fell by a quarter from 2008 to 2012.

Original Sightline Institute graphic, available under our free use policy.

Measured per person, the shift away from paper mail is even more dramatic, as the next figure shows. Per-person mail volume almost doubled from 1977 to 1988, largely because of the explosion of junk mail. It zigzagged higher for a period, then plummeted in the Great Recession. The number of pieces of mail per person in the United States has dropped by a third in the last decade, from 14 to 9 per week. It’s now at a level last seen in 1981, the year Ronald Reagan moved into the White House.

Original Sightline Institute graphic, available under our free use policy.

The steepest decline, among major categories of mail, has been first-class letters with stamps. They’re down more than half in the past decade. Advertising mail has declined less, but it’s still down by a third per household over the last decade, as the next figure shows, from 18 to 12 pieces per household per week. (Note that the previous figure was per person and this one is per household.)

Original Sightline Institute graphic, available under our free use policy.

My own junk mail, by the numbers

My own junk mail has diminished much faster than the US average, dropping by two-thirds over seven years. But, of course, I’ve been stemming the tide aggressively.

In my most recent 12 months of junk mail, unlike in past years, I found no single category of egregious offense: no phone books or Red Plum. Most of the catalogs and repeat mailers I purged in the past stayed purged. But new things crept in, most of them addressed not to me but to my now-adult children (who rarely live at home). My eldest son’s alumni association sent him a dozen pleas for contributions. My daughter got five catalogs from Aerie, a subsidiary of American Eagle. (We asked American Eagle to stop sending its catalogs last go-round, which it did, but it started sending Aerie catalogs instead.) My youngest son, meanwhile, took the medal for most pieces from a single mailer: he received 17 appeals from Planned Parenthood.

Between us, we got 20 mileage plan offers, most of them pushing credit cards. United Airlines, the previous worst offender in this category, ceased and desisted, as I requested in 2013, but others (I’m looking at you, Delta) piled on, mostly targeting my children. Ten other credit card offers also rained down on them, absent mileage plan offerings. US Bank, which used to bother me but stopped when I asked, was the main hawker.

Personally, though, I did get 16 mailings from the Wall Street behemoth Chase, all of them marketing offers for credit cards or bank accounts. Eight of them were a succession of the exact same glossy brochure, dispatched every few weeks to my mail box.

Some formerly dominant categories of junk mail in my pile shrank: Broadband marketers finally listened to my pleas and spared me their relentless junk. Cell phone companies only sent six measly postcards this year. The New York Times, however, still hasn’t honored my twice-made request to stop pitching me a(nother) subscription.

The remainder was election mailers and a miscellany of one- and two-time pieces: local shoppers; coupons from carpet cleaners and eyeglass makers and health-food vendors; two mailings from a mattress company to my ex-wife, who moved out nine years ago; announcements of art openings, theater performances, and community festivals; utility promotional offers; and announcements of new businesses, such as pizza parlors.

I’ve just completed another round of pleading for respite, firing up Catalog Choice again and emailing other advertisers directly. On January 1, I’ll start a new pile, and we’ll see if 2017 is the year that the junk mail poundage stays in single digits.

But as I’ve said, it shouldn’t be this hard. A Do Not Mail Registry would let me opt out once and for all. Unfortunately, the near-term odds of enacting such a legally binding mail box filter are slim. Here’s why.

Why the US has a “Do Not Call” registry, but not a “Do Not Mail” one

The history of the US national Do Not Call Registry sketches the most likely path to a Do Not Mail Registry. It also spotlights what a hard path it is to follow.

When the 1990s began, telemarketers were placing about 18 million calls per day to US phones; by 2002, that number had more than quintupled to 104 million—about one call per household per night. The people picking up those receivers were not happy. They complained, in growing numbers, to the Federal Trade Commission (FTC). From 1998 to 2002 alone, complaints multiplied tenfold. In response, Congress established the Do Not Call Registry in 2003, creating a way for telephone owners to opt out. It was wildly popular. Americans registered more than 10 million numbers in the first four days. By the end of 2015, the registry totaled 222 million.

Unfortunately, telemarketing companies, led by the Direct Marketing Association (DMA), succeeded in slowing implementation of the Do Not Call Registry for more than a decade. The DMA argued that the registry would damage the economy and result in 2 million lost jobs (see page 4,631). Further, it claimed the industry could effectively regulate itself with its own opt-out list (the now-defunct Telephone Preference Service).

Similar to the telemarketers of the 1990s, ad mailers today send daily doses of advertising into US homes and workplaces: two pieces per day on average. Postal customers want a Do Not Mail Registry: in fact, a 2007 Zogby poll reported that 89 percent of Americans wanted one. Nevertheless, the public is not as incensed by junk mail as it was about telemarketing; for one thing, mailings do not interrupt family dinners. The FTC gets lots of junk mail complaints but not as many.

The DMA has launched a spirited defense of ad mail. It has claimed that a Do Not Mail Registry will damage the economy and has shed crocodile tears for the future of jobs for letter carriers. It has again argued for industry-led regulation through its own direct mail opt-out list DMAChoice. The DMA has even set up its own political coalition, Mail Moves America, to block Do Not Mail.

State action helped nudge forward federal action on Do Not Call. By the time Congress established the national Registry in 2003, some 19 states had already set up their own. A similar number of states have attempted to establish Do Not Mail legislation, but not one has yet succeeded. Seattle attempted to prompt a Washington State Do Not Mail list in 2010, and it created a city-wide opt-out registry for phone books. Spokane considered a similar initiative that year, but it did not pass the city council. Unfortunately, Yellow Pages successfully sued Seattle two years later, arguing the ordinance violated its First Amendment rights, an argument that had been ineffective for the DNCR.

Canada’s anti-junk mail solution: A simple red dot

The situation in northern Cascadia, British Columbia, is somewhat better.

Although Canada does not have a national Do Not Mail list, it does have—like Australia, the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom—a program allowing individuals to opt out not of all junk mail but of one major category of it: unaddressed mailings. Sometimes referred to as “saturation mailings,” these ads are delivered to every resident in an area (think RedPlum).

British Columbians who want to quit receiving unaddressed advertisements can put a red dot on their mail boxes, telling their letter carrier to withhold unaddressed paper-spam. Thanks to this program, among other things, Canadians get dramatically less paper in their mail boxes than Americans do: about five pieces per person per week, on average, rather than nine.

To win a Red Dot counterpart in the US parts of Cascadia would require action from USPS headquarters in Washington, DC, and probably from Congress, which seems no more likely in the near term than winning a Do Not Mail Registry. And states, which could in principle approve Do Not Mail Registries, do not have jurisdiction to require letter carriers to mind Red Dots.

So none of these approaches seems likely to come quickly. Public anger is not intense. Junk mail is dwindling anyway. Conservative legislators tend to heed the lobbying of the Direct Marketing Association and its ad-mail propagators; progressive legislators tend to heed the lobbying of the postal unions. Both the marketers and the letter carriers prefer to keep ads flooding our mail boxes, for their own near-term self-interest. The public interest—a mile wide but an inch deep—has few advocates.

The prospects for junk mail to jump to digital

If policy stagnation seems likely, technological stagnation does not. And information technology will no doubt keep suppressing junk mail, especially if one particular thing comes to pass. A fundamental barrier to direct mail marketers leaping the barrier from physical to digital is that email addresses are private, while physical addresses are not.

At present, for example, a new local restaurant has no way to send digital messages to homes in its neighborhood: it can only send physical mail. Unfortunately, the US Congress has banned the Post Office from creating virtual mail boxes for each address, and the one private company that tried, called Zumbox, foundered and sank in the start-up phase.

Still, postal services and private companies (here, here here, here, here, here) keep trying to hybridize mail and email, in hopes of hurrying the wanted messages onward without so much unwanted paper. And as soon as someone figures out how to give every physical address a virtual counterpart, a substantial share of marketers will stop paying for expensive paper and start sending almost-free email. Once that comes to pass, which seems inevitable given the speed of technical change, opting-out will be as easy as clicking “unsubscribe.” This change would not doom all junk mail, but it would take a big bite out of it.

How soon? I wish I knew. I’ll keep watching info tech chip away at junk mail’s domain. I’ll keep wishing for a Do Not Mail Registry. I’ll keep stacking my junk mail, and, with Catalog Choice’s help, appealing to its purveyors to cut me a break. And I’ll tally my mail again after another year has passed, because 15 pounds is 15 pounds too much.

P.S. A post-junk mail postal service

Every time I write about junk mail, a handful of readers object that stopping junk mail will lead to unemployed letter carriers. So let me preempt the objection: the financial troubles at the USPS are largely caused by Congress, which micromanages postal rates and constrains the service’s choices. Granted even a modicum of independence, the Post Office would do just fine. Canada Post broke even year after year, more or less, on not much more than half the mail volume per customer as the USPS, despite much longer distances to travel.

USPS postal rates, furthermore, are much lower than they could be. As Devin Leonard, author of a new history of the US Postal Service, writes:

U.S. postal rates are among the lowest in the industrialized world. In 2015, according to the USPS, it cost 96¢ to mail a 1-ounce letter in Britain and $1.51 to send one in Denmark, which is about 200 miles across at its widest, roughly 3,800 miles less than the distance from Anchorage to Palm Beach. Until recently, Spain was the only nation in the developed world that charged less; now the U.S. and Spain are tied at the bottom.

Comedian Kathleen Madigan hilariously illustrates this point: you can walk into a Post Office anywhere in the United States, hand over an envelope, pay 47 cents, and say “take this to Alaska!”

The postal service employed enormous numbers of people before the junk-mail surge that started in the late 1970s. It can still employ huge numbers in its next incarnation, in a world in which much less communication travels as paper but much more shopping takes place online. What is most valuable in postal services is not their ability to deliver pound after pound of unsolicited advertising pap to each mail box each year but their massive infrastructure for delivering other things: things of greater value, whether love letters, mail-in ballots, or parcels.

The US Postal Service is particularly impressive. It handles 40 percent of all items mailed worldwide each year, and it does so remarkably well—more efficiently and quickly than most national postal services, despite the breadth and diversity of the country it serves. Its logistics, mail sorting, and information technology are, if the butt of many jokes, nonetheless unrivaled. (Did you know that it already takes a picture of every letter and package it handles?)

The USPS physically touches almost every business and home address in the United States almost every day of the week. In its earliest decades, most of what it delivered was newspapers, and it received direct public subsidies most years for almost two centuries. Today, it relies heavily on junk mail. In the future, it may become principally a super-efficient delivery service for online purchases, perhaps even for countless recyclable artifacts 3D printed locally to consumers’ specifications. Who knows? Employment levels will probably change, but postal service itself will endure. Congress’s micro-management, not the crusade to let people say “no” to junk mail, is the real threat to the US Postal Service.

Thanks to Margaret Morales, who provided much of the research for this article, and to Devin Porter of GoodMeasures, who designed the figures.

Notes on Methods and Sources:

We estimate that marketers produce 4,882,000 tons of junk mail paper annually in the United States. This estimate is based on the 2012 USPS Diary Study (see page 40) which states that 86 percent of advertising mail is Standard Mail and 13.8 percent is sent First Class. Using these rates, we added estimates of municipal solid waste categories by weight from the EPA’s 2013 Materials Management Report (see page 39). This report states that 4,150,000 tons of standard mail is disposed of annually, indicating that approximately 732,000 tons of advertising mail is sent First Class.

The charts in this article are based on data from this US Postal Service information page, US Census Bureau population data, and several editions of the annual USPS publication “Household Diary Study” especially those for 2014 and 2015. Canada’s mail volume (9 total billion pieces in 2015 from Wikipedia’s entry on Canada Post), divided by Canada’s 2015 population from Statistics Canada (here), suggests 4.8 pieces of mail per capita per week.

Cass Martinez

Everyone should know that Congressional micro-managing includes the 2006 requirement that USPS create a fund for retiree health care— pre-paying for the next 75 years.

This hidden tax on postage has created quite a lot of pocket money for Congress, and has the added benefit (to the movement to privatize public non-profits) of putting every postal budget since 2012 in the red, since the postal service could not make the last four payments and carries these over on their accounting.

In the meantime, Congress has legislation in the works mandating that postal retirees be moved from the Federal Employee Health Benefits Plan to Medicare, which all postal employees also pay into.

Keep an eye on this $30 + billion slush fund under Congress’s control. If postal employees transfer to Medicare coverage, should the $30B be reimbursed to customers, or should it be used to make USPS’ vehicle fleet electric, or will it be used to shore up Medicare?

Andy Kerr

I had very good luck with https://www.41pounds.org, a paid service that contacts mailers on your behalf. Where they can’t they fill out postcards for you to send to the others.

Steve Erickson

“Once that comes to pass, which seems inevitable given the speed of technical change, opting-out will be as easy as clicking “unsubscribe.” ”

I gave up on clicking unsubscribe because it took way longer than simply hitting delete for the crap that got past my spam filter. Most annoying was the political spam that required me to go to their website and then required me to respond to a follow up email confirming that I was opting-out. Whoever came up with that annoyance should be in jail for a class A felony.

Karen

Advice, please? I’m on a paid site called Classmates. After the first year, I tried to unsubscribe. No luck–even after several letters to them. I tried again after the second year. Same thing. I recently learned that others are having the same problem. How do we resolve this?

Thanks!

Car-Free Lady

“…announcements of art openings, theater performances, and community festivals; utility promotional offers; and announcements of new businesses, such as pizza parlors.”

I wouldn’t consider these as junk mail. But, I guess one person’s ‘junk’ is another person’s ‘treasure.’ 🙂