Original Sightline Institute graphic, available under our free use policy.

In 2009, the citizen-driven Tea Party spread like wildfire, shocking the American political establishment and pundits. Overnight, well funded backers were leaping at the chance to harness this new display of public power. Eventually, hundreds of local Tea Party groups across the US translated their collective strength into substantial results, putting favored candidates into office and influencing the direction of local, regional, and national politics.

As a graduate student at the University of Washington, I studied how Americans develop political clout as “the public.” For my research, I attended Tea Party rallies and events around the country, interviewing dozens of members to find out what was driving them to take action.

It’s true that Tea Party anger sometimes came across as extreme. While they showed that citizen voices can impact American democracy, they may have also set the stage for increased divisiveness in American political culture. Given even sharper language in 2016, it’s perhaps more important than ever to understand that the movement’s success wasn’t dependent solely on hostility. Behind the scenes, the story is a bit more complex. And love them or hate them, the Tea Party showed that citizen voices really can add up to something big.

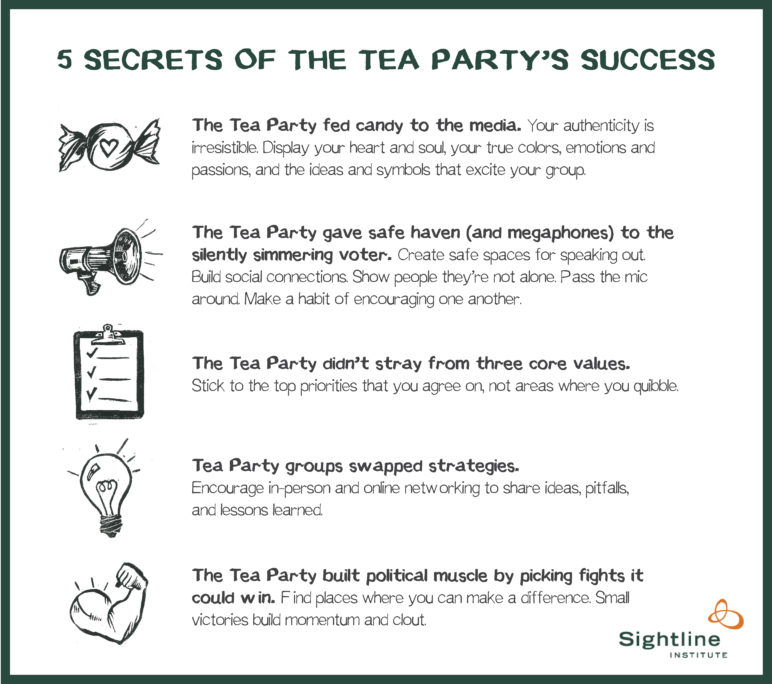

So, how did the Tea Party turn regular, even highly cynical, Americans into an army of engaged citizens? The political and cultural moment that launched Tea Party was unique, to be sure. But here are some strategies that set the Tea Party apart, gained it instant attention, and built—in short order—real power.

These strategies aren’t really secret, of course, or even necessarily new, but the Tea Party offers lessons that any grassroots group would be wise to review.

![]()

1. The Tea Party fed candy to the media

Tea Party protests were irresistible political theater for news media. Some of the early success was about novelty. The Tea Party was an unusual protest movement, featuring older, whiter, more conservative members who weren’t used to taking their views to the streets (that kind of action was considered by many Tea Partiers the domain of hippies and Lefties).

But beyond that, members’ intensity and authenticity were key factors: their heart and soul, their true colors were on display and the media couldn’t get enough. Tea Party protesters loudly embraced patriotic slogans and symbols, and most were extremely passionate and vocal. They demonstrated their commitment in authentic, home-spun ways that made great TV footage—that is, by chanting, dressing in costume, waving flags, and brandishing provocative signs. The attention they earned was tremendously exciting for participants, and when events garnered headlines, it encouraged others to join in and start groups of their own.

You won’t recreate the Tea Party’s particular brand of patriotic passion in your grassroots organizing, but you can stir up your own flavor of media “candy” by celebrating what is different about your group, encouraging individuals show their true colors, rallying around the symbols that excite and unite you as a group, and amplifying the most authentic and powerful resource that your recruits bring—namely, their own deepest personal and emotional reasons for showing up.

![]()

2. The Tea Party gave safe haven (and megaphones) to the silently simmering voter

In 2009, many conservatives, especially many consumers of right-wing news media, were anxious about longstanding cultural shifts they felt were occurring in the US, as well as about what they saw as the political corruption of Presidents Bush and Obama. But for these conservatives, speaking their minds in public was daunting and unfamiliar. Tea Party events prompted many people to protest or speak out in public for the first time. People who had felt shut out, misunderstood, and alienated were encouraged to vent their frustrations and talk about themselves, their families, and what they wanted—and into a microphone, no less!

While Tea Party protests were often very public, participants felt safe. They were among friends. They had found “their people.” Their voices finally mattered. They spoke from the heart, rather than from a press release, often in front of a cheering crowd.

Most importantly, speaking out made them feel like proper, boisterous Americans having their say. Instead of “screaming at the TV,” they were suddenly living the role of upstart rebels, real citizens in the long, noble mythology of American history. Rather than being ignored or left behind, they were raising their voices, taking action, and making a difference. And once they experienced that, they were hooked.

How can you create similar safe spaces for speaking out? Pass the mic around. Ask for people’s personal stories. Show people they’re not alone. Celebrate what sets you apart. Make your events into social occasions. Make a habit of encouraging one another. And rather than simply asking people to share a post, sign a petition, or make a contribution, find ways to invite them into the bold, raucous, joyful tradition of American politics!

![]()

3. The Tea Party didn’t stray from three core values

Across the country, Tea Party groups were laser-focused on what they called their “three core values”: individual liberty, fiscal responsibility, and Constitutionally limited government. From local meetups to the national Tea Party Patriots network, there was virtually lockstep agreement that these issues—and only these—were their primary focus.

Motivated largely by opposition to the TARP economic bailout, the three core values gave members a well structured case against what they saw as government overreach. These values resonated powerfully with conservatives and represented a shared agenda that any group could buy into. By sticking to these values, they avoided getting bogged down in arguments over more contentious issues that could divide, delay, or sidetrack groups.

Keeping a clear and narrow focus invites more people in and avoids alienating others over inevitable differences. By experimenting with this stripped-down approach, you may be able to avoid quibbles about top priorities and fast-forward to high-impact campaign activities. Note: This is not to recommend that groups simplify to such a degree that they ignore important voices and vulnerable populations. A group’s priorities are most meaningful when they bubble up from the bottom rather than come down from the top. The point is to stick to the few you’ve identified that unite your coalition.

![]()

4. Tea Party groups swapped strategies

Individual Tea Party groups were often made up of first-time political activists. But as the movement grew, these scattered, local groups stayed in touch, shared good and bad experiences, and built up their expertise.

A significant number of Tea Party groups in 2009-10 were started by one person who simply had caught wind of other protests on the news. It’s true that there were national organizations in the Republican establishment that provided training (e.g., Americans for Prosperity and FreedomWorks, both of which are backed by the conservative Koch brothers).

But the overriding pattern was that rag-tag local groups organized themselves and rejected any top-down direction. It was through local-to-local networking where groups learned the ropes. Rather than reinventing the wheel in each location, these networks became pipelines for sharing strategies and lessons learned, helping groups become more and more effective in, for example, mobilizing volunteers, spreading news about candidates, and getting media attention.

What’s the lesson here? Nothing beats in-person connections, but technology (some of it free) is perfect for networking and sharing ideas across groups. Post good ideas and debrief bad ones. This not only streamlines processes and boosts effectiveness but also can empower participants as emerging leaders and make people feel a part of something bigger.

![]()

5. The Tea Party built political muscle by picking fights it could win

While the rhetoric of the Tea Party favored sweeping national change, their actual achievements were often local, practical, and even downright modest. They figured out where they could have an immediate impact and put their energies into small wins.

The Tea Party has always been a balance of local and national groups. But the local level is where they had their first and most significant impacts. Many groups chose one or two local-level elections (such as a candidate for the state legislature) or a state-level bill (such as Arizona’s SB 1070, increasing immigration restrictions), and then they worked relentlessly toward that goal. Occasionally, a handful of local groups worked together to elect a candidate to Congress. They focused on sleepy primaries where nobody expected much of a fight. This way, the Tea Party scored some early dramatic wins in 2010. For example, Republican Senator Bob Bennett of Utah, the “establishment” favorite, was ousted that year by Tea Party-backed Mike Lee, who still holds that seat today.

Small wins gave groups the taste of victory and built momentum. And all the little victories tallied around the country added up to a greater voice for Tea Party conservatives in Congress and a deeper “bench” for the hard right in state and local politics.

Most organizations have broad, high-level goals, but it’s worth remembering that every small victory can help pave the way in the direction you’re going. In fact, you may want to purposefully pick a small, winnable fight, especially as you’re getting started.

The bottom line: Restore Americans’ trust in their own democratic power

So many people in the US feel isolated, frustrated, and powerless. In spite of this, no matter how cynical or checked out they get, and no matter how divisive things seem, the vast majority of Americans still have faith in a foundational part of the American story: the belief that We the People—the public—have a special, almost sacred, power in our democracy.

Whatever you think of the Tea Party, one thing it did was restore trust in this story, showing that the grassroots—the public—can make a difference. Regular people who had long felt shut out of the process flexed their civic muscle in the Tea Party, and they saw quick and enormously satisfying results.

Many Tea Party groups that formed in 2010 are still meeting each week, still vetting candidates, and still finding ways to influence receptive politicians. If any groups can borrow a few pages from their playbook and get more people participating and feeling a sense of efficacy, then that’s a big win for all Americans—and for democracy itself.

Download and share the graphic here.

Note from Anna Fahey: Sightline Fellow Colin Lingle studied the Tea Party for his doctoral dissertation in political communication from University of Washington—that’s where I met him. Often, PhD dissertations sit on the shelf gathering dust. But wouldn’t it be great if we could extract practical applications from all that ethnographic research and qualitative analysis? That’s what we did here! For all its faults, we thought it would be valuable to share some of the ways the Tea Party exemplifies how the “public” can have a bigger influence in American democracy. If many more groups elevated voters’ voices this way it would certainly be a win for participation and many of the issues we care about. Colin has also been pitching in on Sightline’s messaging research on housing affordability and democracy reform projects. He received an MA from the School of Journalism and Mass Communication at CU-Boulder and a BA in American Studies from Yale.

Noah Pardo-Friedman

Mr. Lingle, do you think the preponderance of relatively affluent white people in the membership of the Tea Party movement helped them succeed where other, more diverse, and presumably less privileged groups may have a more difficult time scoring victories? And if so, do you think that has to alter the approach that such a group takes?

Colin Lingle, PhD

Hi, Noah. Thanks for those questions. Race is a relevant dimension of the Tea Party story, and I think it’s more than reasonable to suspect that the general legitimization of white versus black voices in our political culture had a role to play in their success, at least in terms of garnering media attention. As we noted above, they were an unusual demographic for protesting, but this was a combination of race, age, and income. In other research I’ve done, the Tea Party was actually subject to a good deal of criticism that media direct toward all protesters (in that study, we compared it to anti-Iraq-war protests and immigration policy protests). So, they didn’t enjoy a completely free pass.

For a superb look at the question of race and the Tea Party, I’d point everyone to the 2014 book by two top-notch UW scholars, “Change They Can’t Believe In: The Tea Party and Reactionary Politics in America,” by Dr. Christopher Parker and Dr. Matt Barreto. [http://press.princeton.edu/titles/9954.html] (The other early, well-established resource on the movement is “The Tea Party and the Remaking of Republican Conservatism,” by Dr. Theda Skocpol and Dr. Vanessa Williamson.[https://global.oup.com/academic/product/the-tea-party-and-the-remaking-of-republican-conservatism-9780199832637]) For more on how media treat protesters generally, you can explore the sub-field of research under the name “Protest Paradigm,” including my colleague Dr. Damon Di Cicco’s work which expanded our understanding to include the “Public Nuisance Paradigm.”

Groups that don’t have that particular built-in advantage might still consider all the steps above. And of course, there are many media outlets that serve a range of diverse communities. Back in February of this year, for example, there was a fantastic panel discussion on “Seattle’s Vibrant Ethnic Media,” hosted by Sightline, the Communications Hub at Fuse, Washington CAN, and Crosscut.com. This was a great discussion about reaching diverse communities and building bridges where traditional media often fail to connect. This is the kind of conversation that many communities are eager to have and would benefit greatly from, I think. Here are a couple of links recapping some of the discussion, and you can join any of these mailing lists to learn about the next time this happens, as well as other great events: [http://latinacreativeagency.com/seattles-vibrant-ethnic-media-panel-discussion-the-first-of-many/][http://washingtoncan.org/wordpress/tag/seattles-vibrant-ethnic-media-panel-discussion/]

In short, our media systems should reflect who we are more broadly (that’s on the establishment media outlets themselves), and we should all support and consume more diverse media as well (that’s on us, as readers, viewers, listeners, and organizers). Thanks again, Noah.

Matt McCloud

A great reminder on the principle of focusing on what works.