UPDATE, AUG 4: We added the first graph, below, to illustrate our analysis.

UPDATE, AUG 3: Friends have suggested that basing some of our analysis on the sum of state tax revenue unfairly biases it in favor of I-732, something we certainly didn’t intend. Our estimated $78 million average annual shortfall is just 0.37 percent of $21 billion in state tax revenue, but it is 3.9 percent of CarbonWA’s $2 billion tax swap. The Department of Revenue’s estimated $200 million average annual shortfall is less than 1 percent of state tax revenue but 10 percent of I-732’s carbon tax revenue. This feedback made us realize we were not clear about the underpinnings and main conclusion of our analysis. We endeavored to determine whether I-732 is as close to revenue neutral as a reasonable forecast can determine. We have added to the article to better frame our assertions and to make clear that our analysis holds whether total tax revenue or carbon-tax revenue is the basis for comparison.

Note from Alan: As I explained last time, Washington’s Initiative 732 has divided climate hawks so deeply that even writing about it is a task we undertake with trepidation. (Please read my full note of introduction to the series here for more background.) We endeavor to remain neutral, supporting action on climate but not siding with one action path over another. We strive, in this short series, to lay out a balanced analysis of the I-732 policy itself and arguments against and for it. We aim to set aside all questions of politics and strategy and just look at the factual arguments. In this article, we examine a major controversy: whether I-732 will create a budget shortfall.

—

Initiative 732, the carbon tax that will be on Washingtonians’ November ballot, is meant to be a revenue-neutral tax swap. A tax swap doesn’t change net state revenue; it just switches out one bit of revenue for another. I-732 would cut the state sales tax, give tax credits to working families, and cut taxes on manufacturers, replacing them, dollar for dollar, with a tax on pollution.

Despite I-732’s intent to be revenue neutral, the Washington Department of Revenue (we’ll refer to it as “the Department” for the rest of the article) estimates that it will actually be revenue-negative. Its tax cuts will outweigh the new carbon tax revenue, leaving the state with less money overall. The predicted budget deficit is the opposition’s number one complaint about I-732—which is understandable, since one of I-732’s big selling points is its revenue neutrality.

But it’s worth asking: How certain can the Department’s or anyone’s forecasts be about the exact budget impact? Are the Department’s estimates for the first four years accurate? How close to revenue neutral will I-732 be over the course of the decades it is written to last? What would it take to make a tax swap initiative revenue neutral over time?

Below, we weigh the evidence on each of these questions, test the logic of and evidence behind supporters’ and critics’ arguments and counterarguments, and go eyeball deep into the weeds of state budget forecasting. But here’s the upshot, in two paragraphs:

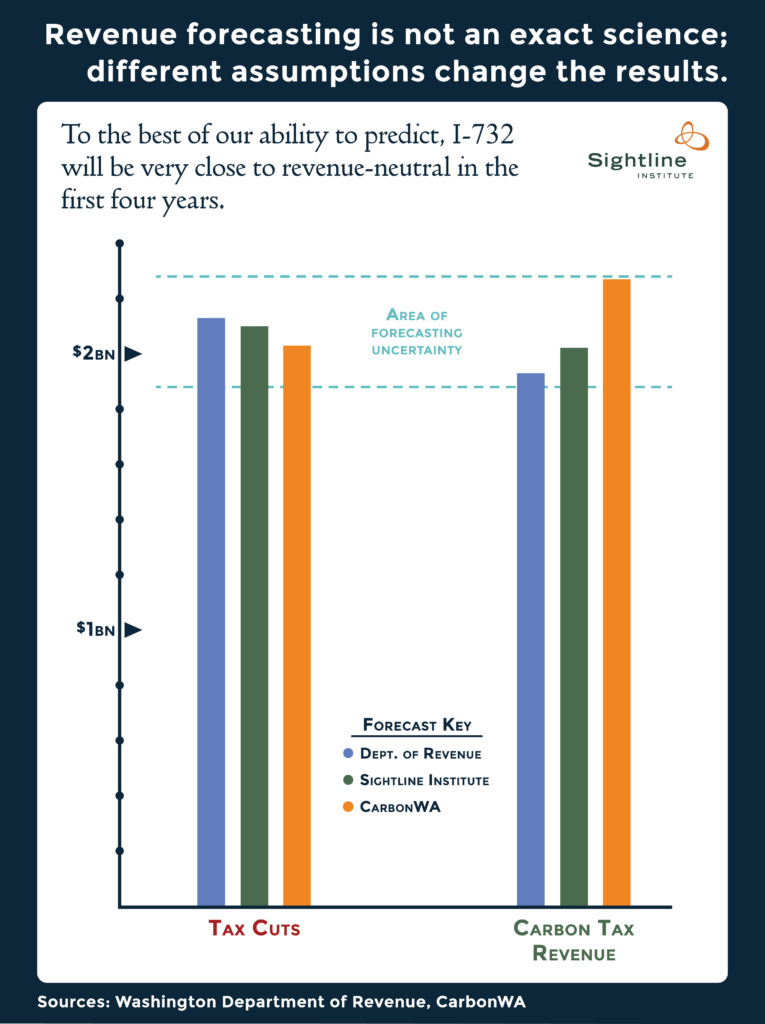

I-732 is revenue neutral, to the best of anyone’s ability to forecast it. The forecast depends on statewide carbon emissions and statewide sales tax revenue that could change by hundreds of millions of dollars a year, depending on how accurate the forecast’s assumptions turn out to be. Whether the revenue balance drifts positive or negative will depend on forces far beyond the drafters’ control: oil prices, growth rates of retail sales, shifts in population and consumer preferences, advances in technology, national energy policies, even the weather. Predicting such things with greater accuracy than a few hundred million dollars per year is impossible. Just as the Department adjusts budget forecasts by hundreds of millions of dollars every few months, and the legislature adjusts its budget every other year, sometimes by more than a billion dollars, the legislature will need to make small adjustments to keep I-732 as close to revenue neutral as possible over time.

In the short term, I-732 is likely to be much closer to revenue neutral than the Department’s forecast suggests. Correcting some errors of fact and logic in the Department’s estimates erases more than half of the Department’s alleged short-term revenue shortfall. We conservatively estimate I-732 will reduce state tax revenue by about $80 million per year in early years, but the limitations of forecasting mean that, for all anyone knows, I-732 could very well generate an $80 million surplus for the state budget. Or some other amount, positive or negative. We simply can’t forecast I-732’s impact with greater precision. But we can say that it is close, and that anyone who claims to know for certain that it will create a budget hole is more certain about the whims of forecasting than forecasting experience warrants. As an argument against I-732, therefore, the “revenue hole” case is a red herring. I-732 has weaknesses, but this isn’t one of them.

How accurately can we forecast revenue neutrality?

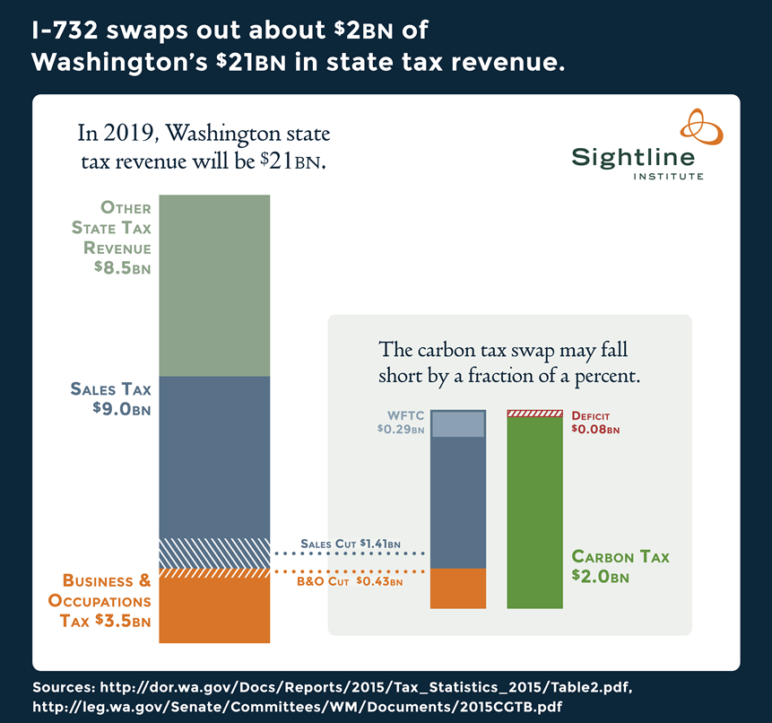

Forecasts often convey a false sense of precision. Revenue is difficult to predict and forecasts are really just estimates, based on elaborate sets of assumptions. They can go up or down several percent if assumptions change. I-732 swaps out about $2 billion of the state’s roughly $21 billion in state tax revenue (predicted in fiscal year 2019), which is one piece of the roughly $45 billion yearly state budget. Can anyone predict I-732’s annual impact down to one million dollars? Ten million? One hundred million? Some other digit?

State tax revenue projections fluctuate by hundreds of millions of dollars in just a few months. The Washington State Economic and Revenue Forecast Council updates its state Budget Outlook three times per year. For the past two years, with each new forecast, the Council has adjusted its predictions for the upcoming fiscal year by an average of $440 million, and has adjusted predictions for four years from now by an average of $1 billion.

Looking just at the $2-billion tax swap, rather than the entire state tax revenue stream of $21 billion, the forecast turns largely on how quickly carbon emissions shrink and how briskly state sales tax revenue grows. If we predict that, in the next four years, state tax revenue will grow at the same rate it did during the 4-year period 2011 through 2014, but it turns out revenue changes instead at the 2008-2011 rate, I-732 would generate $500 million per year more than we forecast. On the carbon-revenue side, if we predict carbon emissions will fall in the first four years as the economy responds to the tax, but instead a growing population means emissions stay flat, I-732 would generate $200 million more per year than we predicted.

The Department’s forecast of a $200 million per year shortfall is well within the range of uncertainty: different assumptions erase or increase it. And, as we explain in detail below, we believe the Department made some errors in its revenue forecast. By its own methods, we think the Department should have forecast a shortfall closer to $80 million per year, well within forecast variability. The Department, Sightline, and Carbon WA all predict I-732 will be within a few hundred million dollars of perfect revenue neutrality. So far as we are able to predict the vagaries of statewide emissions and statewide tax revenue, in its first four years, I-732 revenue balance will be within the limits of our ability to forecast.

Revenue neutrality in the short term

If passed, when fully implemented in 2019, I-732 would cut sales tax and business and occupation (B&O) tax revenue by around $2 billion per year and raise around $2 billion per year in carbon tax revenue, swapping out about 10 percent of the approximately $21 billion in state taxes Washington will likely collect in fiscal year 2019.

The Department estimates I-732’s tax revenue will fall short of the tax cuts by an average of $200 million per year in the first four years, impacting state tax revenue by less than 1 percent. (Another way to put $200 million per year in context: it’s about 4 percent of the additional $5 billion per year that plaintiffs say Washington needs to spend on K-12 education.) Even if the Department’s estimates are correct, I-732 will still be a rounding error, decreasing state tax revenue by less than 1 percent.

However, we conclude that the Department’s estimates are off. Giving the Department the benefit of the doubt on several modeling questions, we predict I-732 will have an impact on state tax revenue in early years of less than $80 million. Forecasts get buffeted by unpredictable forces, so we aren’t saying we know I-732 will have that impact. There’s almost as much chance that I-732 will be revenue positive by a similar amount. What we are saying is that, using the best predictions available, I-732’s divergence from perfect revenue balance is within $100 million, and unpredictable factors could bounce that number up or down. The only thing we or anyone can know for sure is that I-732 is either revenue neutral or close.

The Department of Revenue’s estimates vs. CarbonWA’s: Refereeing the blow-by-blow

The Department of Revenue has issued three fiscal notes for I-732: in December 2015 the Department estimated a $675 million deficit over 6 years; the following month, in January 2016, it issued an updated fiscal note estimating a $915 million deficit over 6 years; and in April 2016 it issued the fiscal impact statement that will go on the ballot, predicting a $797 million shortfall over six years. We use the most recent estimate and divide by four years instead of six (the six-year analysis runs from fiscal year 2016 through fiscal year 2021, but I-732 will only take effect in fiscal year 2018), for an average annual state tax deficit of $200 million for the first four years.

I-732 backers argue the Department made several errors in its estimates, and that correcting these errors would reveal that I-732 would actually be slightly revenue-positive in its first four years. In public comments filed in January, CarbonWA pointed out a list of errors. In February the Department responded, declining to make any changes to its estimates. The Department made other adjustments to its December estimates in April 2016, adding about $30 million more to its projected average annual deficit in the first four years of the program. (The fact that the Department’s forecasts bounced around by tens of millions of dollars underscores our point that forecasting is not an exact science. The best anyone can say for sure is whether I-732’s fiscal impact is within the margin of error of the forecasts.)

Below are CarbonWA’s claims and Sightline’s analysis of each.

CarbonWA Claim #1: The Washington carbon tax should apply to electricity exported out-of-state.

CarbonWA argued that the carbon tax should apply to electricity generated in Washington but consumed in another state. The Department disagreed, noting that Section 4 of the initiative only refers to electricity “consumed” within Washington, that Section 5 exempts exported fuels, and that the US Constitution forbids a state from taxing an activity, such as consumption of electricity, that occurs outside the state.

Two questions arise:

- Is electricity a “fuel”?

- Does Washington have the legal authority to tax exported electricity?

I-732 taxes carbon through two avenues: first, the carbon content of “fossil fuels sold or used in this state,” and second, “the carbon content inherent in electricity consumed within this state.” See Section 1(1) and Section 4(1).

To avoid double-counting fossil fuels burned in Washington to generate electricity consumed in Washington, Section 5(4) specifies the tax only applies once, to the fuel burned. Utilities don’t pay the tax for electricity consumed in Washington if they can show they already paid the tax on the fossil fuels burned to generate the power. Utilities will only pay the tax on electricity sold in Washington if the fossil fuel used to generate the electricity was not sold or used in Washington. In short: I-732 taxes all fossil fuels sold or used in Washington, whether to generate electricity or for any other purpose, and it also taxes electricity brought into the state that was generated by burning fossil fuels outside the state.

Section 5 exempts three categories of fuels from the tax: (a) fossil fuels inside the supply tank of a car, ship, train, or airplane; (b) fuels the state is constitutionally prohibited from taxing; and (c) fuel intended for export outside the state.

CarbonWA interprets “fuels” in Section 5(c) to mean “fossil fuels,” defined in Section 3(8) as including petroleum, coal, natural gas, propane, bunker fuel—but not electricity. The Department interprets “fuels” in Section 5(c) as an undefined term that includes electricity.

Unfortunately, the text is ambiguous. To enact CarbonWA’s interpretation, Section 5(c) should have said “fossil fuels” instead of “fuels.” Courts usually assume the drafters knew what they were doing, so if they said “fuels” instead of “fossil fuels,” they must have meant something different than “fossil fuels.” Since “fuels” is not defined in the text, the Department might look to the dictionary to determine how to interpret the term. The Merriam-Webster Dictionary defines “fuel” as “a material (such as coal, oil, or gas) that is burned to produce heat or power.” This suggests the usual interpretation of “fuels” is a material burned to create power, but not the power itself.

We believe the Department could reasonably define the term “fuels” in Section 5(c) as the standard dictionary definition of fuels and thus conclude that Section 5(c) does not exempt exported electricity.

CarbonWA’s interpretation has the added merit of simpler implementation. Under the Department’s interpretation, utilities would need to seek a rebate for the tax paid on fuels burned to generate electricity they ended up exporting. Under CarbonWA’s interpretation, a utility with a gas-fired plant would pay the tax for the natural gas, then submit a report to the Department, per Section 7, showing that it already paid the tax on the natural gas and so doesn’t have to pay it for any electricity its plant generated. Under the Department’s interpretation, the utility would do all that but also prove to the Department that it exported some portion of its electricity and so should get a rebate of the tax already paid on the natural gas burned to generate the portion of electricity it exported.

The Department’s argument about the US Constitution prohibiting a tax on exported electricity is confusing. Presumably the Department is referring to the dormant commerce clause—a legal doctrine prohibiting states from discriminating against interstate commerce by instituting policies to protect in-state industries at the expense of out-of-state competition. A classic example of a state violating the dormant commerce clause is when an Arizona law required all cantaloupes grown in Arizona to be packaged in Arizona as a way of protecting the Arizona packing industry against competition from California fruit packers. A federal court invalidated the protectionist law.

If Washington tried to levy a tax on power imported from other states but not on in-state power, a court might strike down that tax as an attempt to regulate activity outside the state in order to protect in-state power producers against out-of-state competitors. But I-732 imposes a tax on in-state activity—burning fossil fuels to generate electricity. If anything, taxing fossil fuels burned in-state to generate electricity sold out-of-state does the opposite of protecting in-state electricity generators; it makes Washington’s exported power more expensive than the non-Washington-produced power it is competing with in markets outside Washington.

We conclude that the structure of I-732 makes clear it is meant to tax all fuel used or sold in the state, whether to generate electricity for consumption or export or anything else, plus all imported electricity. The Department’s interpretation of the ambiguous term “fuels” conflicts with the dictionary definition and adds implementation complications. Applying the tax to all fuels used or sold in the state, without a carve-out for fuels used to generate electricity that is ultimately exported, would be more reasonable and straightforward. We conclude that I-732 should apply to exported electricity.

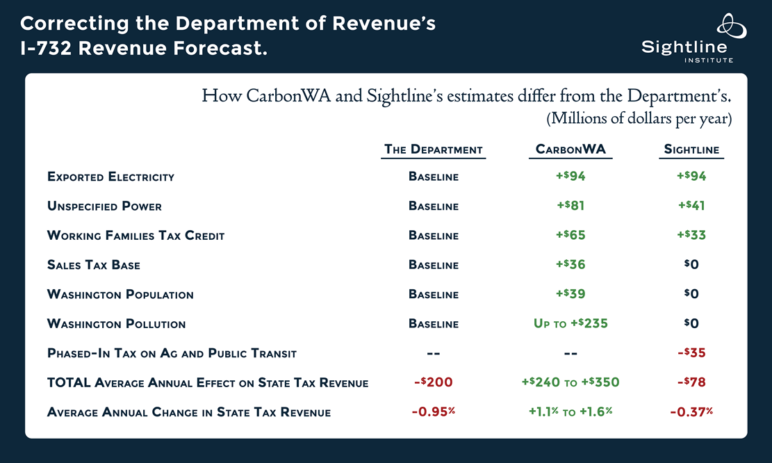

CarbonWA estimates that, if its claim that the tax applies to exported electricity is correct, this change would reduce the budget gap by almost half—about $94 million per year. Our interpretation is that the Department should tax exported power and add $94 million per year to its revenue forecast.

Sightline Estimated Average Annual State Tax Revenue Impact: +$94 M

CarbonWA Claim #2: I-732 would tax unspecified power at a higher rate.

CarbonWA claimed that the Department used the wrong tax rate for unspecified power. The Department used the default emissions rate in the Carbon Tax Assessment Model (CTAM), the “Northwest Power Pool Net System Fuel Mix,” which is the average emissions rate of all electricity that is known to be a part of the Northwest Power Pool but is not specifically claimed by a utility. CTAM calculates The Net System Fuel Mix to be 38 percent coal, 14 percent natural gas, and 48 percent non-fossil-fuel resources, or an average of less than half as much carbon pollution as a coal plant.

However, I-732 would tax unspecified power as if it all came from a coal plant. Section 7 of the initiative orders the Department to assign unspecified power an emissions rate of “one metric ton of carbon dioxide per megawatt hour.” One metric ton is 2,205 pounds, or about the same level of emissions as a coal-fired power plant, more than double the Net System Fuel Mix emissions rate in CTAM.

The Department argued that utilities would be motivated to identify the sources of all non-coal unspecified power to avoid paying the carbon tax as if all that power were coal. Because utilities would specify the sources of 100 percent of their previously unspecified non-coal power, CTAM’s Net System Fuel Mix rate is correct.

Unspecified power generally comes from four sources: the spot market, bilateral agreements between utilities, utilities that choose not to specify, and null power (the power that remains when someone else has purchased the power’s renewable attributes). Utilities will be able to specify sources in bilateral agreements and sources of power they simply chose not to specify. They will not be able to specify sources of spot market purchases nor sources of null power. The spot market is an integral part of the Western grid, and unless Washington utilities cease purchasing any power on the spot market, the Department is incorrect to assume that 100 percent of non-coal unspecified power will become specified.

Where the Department assumes 100 percent of non-coal unspecified power will become specified in fiscal year 2018, CarbonWA estimates that 36 percent of non-coal unspecified power will become specified in fiscal years 2018 and 2019 and 73 percent will become specified in fiscal years 2020 and 2021. This change to the Department’s assumptions would increase revenue by about $81 million per year. We adopt a stance halfway between the Department and CarbonWA, assuming that 68 percent and then 86 percent of currently unspecified non-coal power will become specified. Under this assumption, the Department should add $40.5 million per year to its revenue estimates.

Sightline Estimated Average Annual State Tax Revenue Impact: +$40.5 M

CarbonWA Claim #3: The four-year forecast should only include four years of Working Families Tax Credits.

Because the state budget runs on fiscal years (July 1 through June 30) and the Working Families Tax Credit is payable anytime during the calendar year (January 1 through December 31), the Department must choose a method of reconciling timelines in order to issue an estimate of revenue neutrality over any particular period. The Department’s four-year forecast, the one that has been the center of controversy, chooses the method for reconciling timelines that makes I-732 look the worst for the state budget.

The Department’s four-year analysis includes four years of carbon tax revenue and five years of Working Families Tax Credits. The Department assumes that 100 percent of 2021 tax credits will be paid by June 30, 2021, just slipping under the wire for inclusion as a fifth year of credits in the four-year forecast. If the Department had chosen to account for those payments one day later, on July 1, 2021, $65 million per year would have disappeared from the Department’s projected shortfall—more than one-third of the estimated deficit. Alternatively, had the Department allocated its expected 2021 tax credit payments in equal increments across the months of calendar year 2021, $32.5 million per year would have vanished from the shortfall.

We split the difference on this question, assuming the four-year forecast should include four-and-a-half years of tax credits and removing half of the estimated liability for 2021 tax credits from the tally.

Sightline Estimated Average Annual State Tax Revenue Impact: +$32.5 M

CarbonWA Claim #4: The reduced sales tax would increase the sales tax base.

CarbonWA explained that people will respond to sales tax savings by spending slightly more. The Department said its model already accounted for this.

We can’t tell whether the Department’s model properly took demand elasticity into account or not. CarbonWA estimates that, if its claim is correct, this change would reduce the budget gap by about $35 million per year.

We gave the benefit of the doubt to the Department.

Sightline Estimated Average Annual State Tax Revenue Impact: $0

CarbonWA Claim #5: The Department didn’t differentiate Washington from the Pacific Region in the model.

CarbonWA said the Department’s model assumes Washington has a fixed share of the Pacific Region’s emissions (the Pacific Region includes California, Oregon, Washington, Alaska, and Hawaii). But Washington’s share of emissions within the region will actually grow in the near term, for two reasons: first, Washington’s population is growing faster than the regional average; and second, Washington’s baseline emissions will grow faster (or shrink more slowly) than California’s in the next four years because California already has many policies in place to reduce global warming pollution.

On the first point, the Department didn’t make a satisfactory response to the difference in population growth, and we can’t tell whether the Department’s model properly took different population growth rates into account or not. CarbonWA estimates that, if its claim is correct, this change would reduce the budget gap by about $39 million per year.

Regarding the second point, the Department said its model already did account for California’s pollution reduction policies. But here again, we can’t tell whether the Department’s model properly accounted for different pollution reduction policies. CarbonWA estimates that, if its claim is correct, this change alone would add about $235 million per year, reversing the budget gap and making I-732 slightly revenue-positive in its first four years.

We found the Department’s responses unsatisfactory, but still gave it the benefit of the doubt. We hope that any future updates to the Department’s model will address this issue directly.

Sightline Estimated Average Annual State Tax Revenue Impact: $0

Bonus: Phased-in taxes

The Department’s analysis did not account for the fact that Section 5(2)(a) phases in the tax slowly over time for fuel use by farmers and public transit. Fossil fuel use by agricultural equipment and public transit account for roughly 2 percent of Washington’s fossil fuel consumption, or about $40 million per year in revenue. They will be taxed at a rate of 5 percent in 2018 and 2019 and 10 percent in 2020 and 2021, for an average annual tax loss of around $35 million per year in the first four years.

Sightline Estimated Average Annual State Tax Revenue Impact: -$35 M

Adding it up

The table below shows how each of CarbonWA’s claims and Sightline’s evaluation of those claims differ from the Department’s. It also shows the difference from the phase-in of fuels in the agricultural and public transit sectors. To read the table, for example, the first line shows that CarbonWA argues the Department understated revenue from exported electricity by $94 million a year. Sightline concurs.

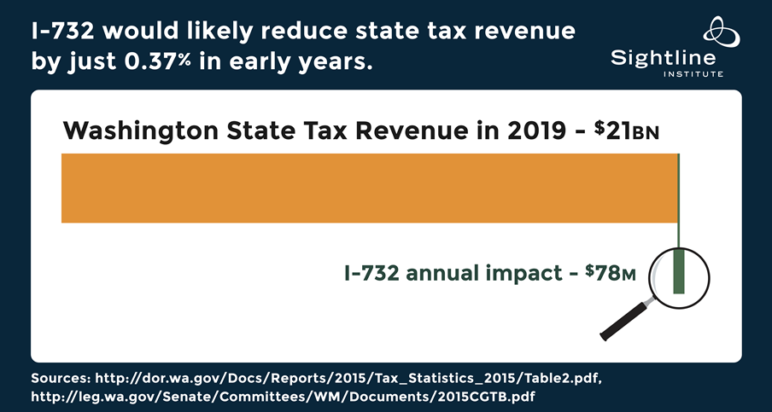

Overall, the Department estimates that I-732 will decrease state tax revenue by just under 1 percent in the next four years. CarbonWA estimates that I-732 will increase state tax revenue by 1.1 to 1.6 percent. Correcting for some errors in the Department’s logic and giving the benefit of the doubt to the Department on several modeling questions, Sightline estimates that I-732 would decrease state tax revenue by 0.37 percent in the next four years—an estimate about two-fifths the size of the Department’s.

As we explained above, economic changes or variable carbon emissions can change forecasts by hundreds of millions of dollars per year. Our forecast shows I-732 is as close to revenue neutral as our forecasting tools can predict. It’s a tiny fraction of the normal quarterly variations in revenue forecasts that the state routinely adjusts to as economic trends shift. Certainly we could not point to this forecast as evidence that I-732 creates a “budget hole.”

Adjusting over time, via state legislature

British Columbia’s revenue neutral carbon tax didn’t promise to have exactly zero budget impact every year with no adjustments. Instead, the BC Carbon Tax Act requires the Minister of Finance to prepare a carbon tax plan every year that reviews the previous two years of carbon tax revenue and tax cuts, forecasts the next three years of revenue and tax cuts, and makes adjustments as necessary to keep the program as close to revenue neutral as possible.

Part 2(2) of the Act defines revenue neutral to mean that the tax revenue is “less than or equal to” the tax cuts, meaning the minister must ensure the carbon tax revenue only funds tax cuts and not any other programs or initiatives. In other words: if the agency can’t adjust tax cuts to make the program perfectly revenue neutral, it should err on the side of being revenue-negative. In its most recent report, the Minister of Finance confirmed that tax cuts would slightly exceed carbon tax revenues.

In Washington, state agencies don’t have the authority to tinker with state taxes; only the legislature does. I-732 would give the legislature the opportunity to make adjustments if the swap gets too far from equal, based on required annual Department reporting about the overall net gain or loss in state revenue due to the tax swap. For example, the legislature could better tailor the tax breaks for manufacturers to ensure they are combatting the competitive impacts of the carbon tax and no more. The Department of Ecology has already been working on identifying the energy intensive, trade-exposed businesses that need assistance to remain competitive with out-of-state companies that don’t pay a carbon price. The legislature could ask Ecology to recommend ways to better tailor the B&O tax breaks and fulfill I-732’s stated intents to remain revenue-neutral and to keep manufacturers in the state.

For most programs, it would be reasonable for a citizens’ initiative to express the will of the people and for agencies to implement the new law in a way that carries out the people’s intent. For example, if Washington voters pass I-732, then the Department of Revenue would implement it in a way that carries out the people’s intent to impose a revenue-neutral carbon tax. However, because Washingtonians only entrust voters and elected legislators with adjusting taxes, it will be up to the legislature to fine-tune tax cuts to maintain revenue neutrality.

Revenue neutrality over the longer term

The analysis above shows how hard it is to know whether a tax swap will perfectly pencil out in the next few years. Extrapolating the same analysis out over decades and expecting it to be accurate within a fraction of a percentage point every year without course corrections is downright Herculean. I-732’s drafters used past sales tax revenue growth to estimate how much of a tax cut the new carbon tax revenue could fund. But will future sales tax revenue follow past patterns? Patterns reaching how far back?

In the analyses below, we assume, for simplicity, that Washington meets its greenhouse gas pollution reduction goals through 2050. The carbon tax alone may not bring Washington all the way to its target of a 50 percent reduction below 1990 levels by 2050, so for this assumption to hold true, Washington will need additional pollution-busting policies.

If Washington over pollutes, the state will bring in more carbon tax revenue than the analysis below assumes. But if the Evergreen State succeeds in meeting its pollution reduction goals, then I-732’s net revenue will be intensely sensitive to changes in sales tax revenue.

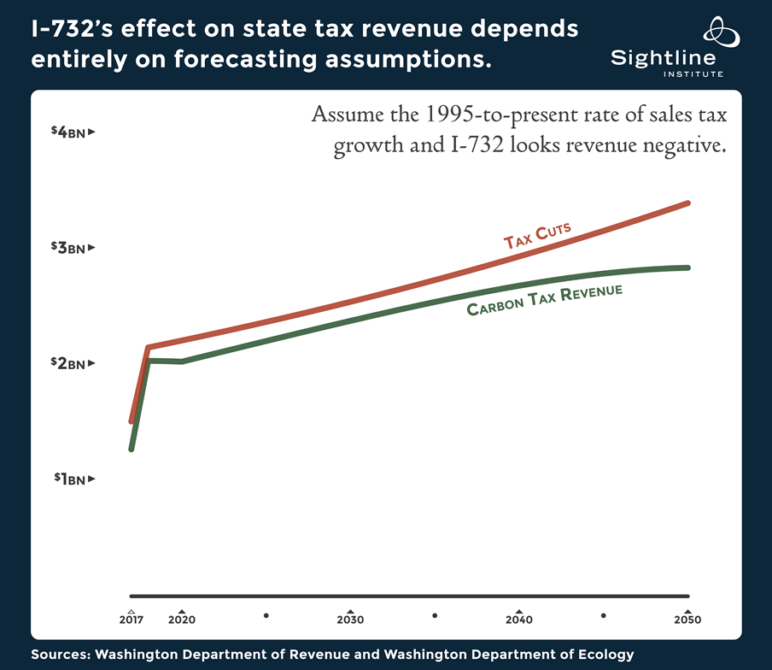

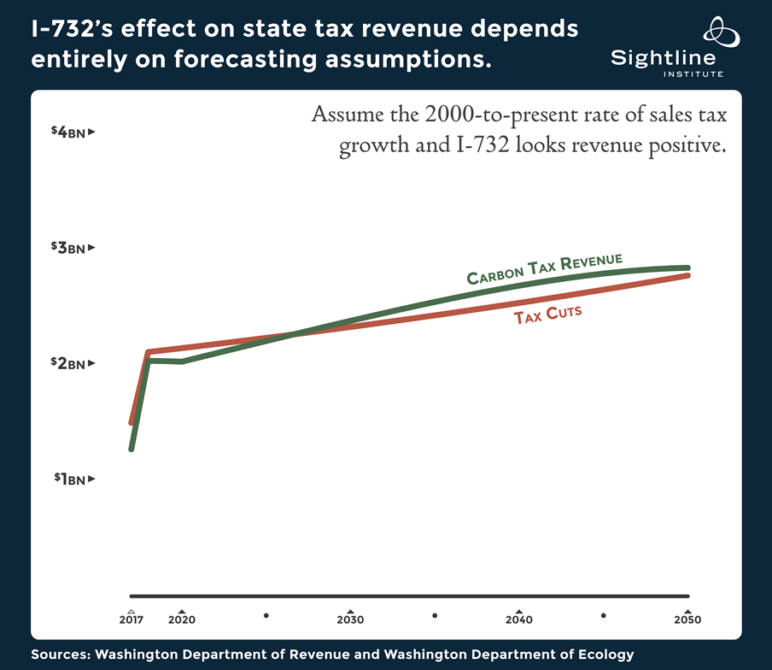

If state sales tax revenue increases at the same rate it has increased in the 20 years since 1995—4.0 percent per year, or 1.6 percent in inflation-adjusted terms—then I-732 will leave shortfalls of less than 1 percent of state tax revenue, around $150 million per year, through the early 2030s. The shortfalls will grow to more than 1 percent of state tax revenue, $200 to $300 million per year, in mid-century.

On the other hand, if state sales tax revenue increases at the same rate it has increased in the 15 years since 2000—3.0 percent per year, or 0.6 percent after inflation—then I-732 will be within a fraction of a percent of revenue neutral during the 2020s and will generate $100 to $150 million in surplus revenue per year in the 2030s and 2040s, adding less than a percent to state tax revenue during those years.

Again: shortening the baseline from 20 years to 15 years of sales tax revenue growth completely flips the forecast from budget hole to budget surplus. That’s just one of many ways in which the long-term revenue implications of I-732’s provisions are unknowable. A few other ways:

- If fuel prices rise one year, fuel consumption will decline, as will carbon tax revenue, pushing the balance toward revenue-negative.

- If a winter is unusually cold, furnaces will burn more fuel, increasing carbon tax revenue, pushing the balance toward revenue-positive.

- If electric vehicle technology sweeps carbon pollution out of the transportation sector faster than required by the state’s carbon pollution goals, carbon tax revenue will drop, and sales tax revenue (and thus sales tax cuts) will rise: revenue-negative.

- If the economy runs off the rails, both carbon tax and sales tax revenue will diminish—sales taxes likely faster than carbon taxes, pushing the balance toward revenue-positive.

To keep the tax swap neutral, the legislature will need to take the Department of Revenue’s annual report into account and make adjustments. As mentioned, the legislature could tighten the B&O tax cuts to keep I-732 from being revenue-negative. Or, if I-732 becomes revenue-positive, the legislature could increase the Working Families Tax Credit, rebalancing revenue and putting more money in the pockets of working families.

So the main answer to the question of whether I-732 is revenue neutral is, to the degree that any short-and-simple initiative can balance tax cuts and a carbon pollution tax over decades, yes. It’s revenue neutral. Even by the Department’s estimate, it’s within 1 percent of neutrality in the near term. By Sightline’s estimate, it’s within 0.37 percent. And as time goes on, the legislature could honor the will of voters to keep it neutral.

Conclusions

Balancing a big package of tax cuts with a new and innovative pollution tax with zero impact on the budget is nearly impossible. I-732 gets extremely close, though.

Even if the Department’s four-year analysis is correct, I-732 creates a 0.95 percent budget shortfall. Correcting some errors in the Department’s analysis—taxing exported electricity, assuming 14 to 32 percent of currently unspecified non-coal power remains unspecified, and including just four-and-a-half years of tax credits in the four-year forecast—and subtracting the revenue lost by phasing in taxes that the Department didn’t account for, we estimate that I-732’s likely budget shortfall for the first four years would actually be just 0.37 percent, or $78 million per year, rather than the Department’s most recent estimate of $200 million per year. Despite the seeming precision of these estimates, they just point in the right direction because any number of factors could shift and change them again. But careful analysis suggests that I-732’s net impact on state tax revenue is almost certainly within the margin where all we can say for sure is it is very close to revenue neutral.

As time goes on, the net revenue will depend on how quickly Washington State reduces its pollution and how briskly state sales tax revenue increases in future years. By current estimates, I-732 will likely have less than a 1 percent impact on state tax revenue for decades. If the Department’s annual report shows the swap drifting too far from neutral, it will be the legislature’s job to tweak the tax cuts so as to carry out the people’s intent of a revenue neutral carbon tax.

[list_signup_button button_text=”Like what you|apos;re reading? Get the latest Sightline carbon pricing research to your inbox.” form_title=”Making Polluters Pay Newsletter” selected_lists='{“Carbon Pricing & Making Polluters Pay”:”Carbon Pricing |amp; Making Polluters Pay”}’ align=”center”]

Comments are closed.