Oregon’s Constitution holds a rude surprise for climate crusaders: Article IX prevents the state from investing revenue from transportation sector polluters—nearly half the potential climate pollution revenue in Oregon—in solar panels, bikes, and buses. The constitution funnels pollution revenue exclusively into the Highway Fund.

Using pollution revenue to build new highways that induce more driving, thus generating more pollution, would create… a climate-change facepalm. But this ominous constitutional cloud has a silver lining—using transportation pollution revenue to maintain local roads would be legal, would create local benefits, and could conceivably even be good for the climate.

Local agencies across the Beaver State struggle to find funding to maintain local streets, sometimes dipping into General Fund money that could instead be used for police, parks, and other local services, and often deferring maintenance and letting the potholes grow. If the state passed pollution revenue on to local agencies for street maintenance, however, the money would fill gaping financial holes in local budgets across the state, would not increase driving and pollution in the way that new highways would, might make it safer for people to walk and bike, and would create local jobs. Not bad…

The problem

Article IX, Section 3 of the Oregon Constitution requires “any tax levied on, with respect to, or measured by the storage, withdrawal, use, sale, distribution, importation or receipt of motor vehicle fuel” to be “used exclusively for the construction, reconstruction, improvement, repair, maintenance, operation and use of public highways, roads, streets and roadside rest areas.” The Oregon Supreme Court has interpreted this section broadly, saying that not only must “tax” revenue be funneled into the Highway Fund, “fees” and “assessments” also get siphoned to the Fund. Even revenue from an “underground storage tank assessment” and an “air pollution emissions fee” must be used exclusively for roads.

Usually, courts draw a distinction between “taxes” (collected from taxpayers generally and used for general government purposes) and “fees” or “special assessments” (collected only from those participating in a certain activity and used for specific purposes that relate to the activity). A California court recently honored this distinction when it classified California’s cap-and-trade revenue as a fee, not a tax, and Oregon courts have also distinguished taxes from “special assessments” in the past. But the Supreme Court of Oregon declined to apply the “special assessment” distinction in the context of Article IX, Section 3(a), because the “clear purpose” of that section “is to prevent diversion from the Highway Fund of money raised from burdens imposed on motor vehicle fuel.”

By the court’s logic, if Oregon institutes a law capping climate pollution, the revenue from motor vehicle fuel pollution will most likely be legally dedicated to the Highway Trust Fund. Pollution from motor vehicle fuels accounts for almost half of the pollution that a climate bill would cap, meaning that Oregon would dedicate nearly half of its carbon revenue to the Highway Fund. This influx of cash to the Highway Fund could enable Oregon Department of Transportation (ODOT)to expand highway capacity, which would counterproductively induce more driving. Or, increased revenue for the Highway Fund could motivate the legislature to decrease the state gas tax, negating or muting the pollution price signal in the transportation sector.

Both scenarios are antithetical to the goal of transitioning off of fossil fuels and onto clean energy. Fortunately, Oregon has two ways out of such a mess.

A plausible solution: Dedicate the funds to local road maintenance

Instead of using climate pollution revenue to build new highways, Oregon could use the money to maintain local roads. Oregon county road departments face a $500 million annual shortfall, and Oregon cities need about $300 million more per year just to maintain local pavement. A pollution price of $13 per ton (the current price in California and Quebec) would raise about $300 million from the transportation sector in the first year. Oregon could spend every cent of that $300 million on county and city road maintenance and still not fill all the potholes.

Well maintained local streets aren’t just a boon to drivers; they make communities more livable for everyone getting around, whether by car, bus, or bike. Buses need well maintained streets to run smoothly and on time, and cities must repave and re-stripe streets in order to install Bus Rapid Transit, so maintenance money benefits transit access.

And maintaining streets doesn’t just mean making them smooth; it can also mean making them safe. Cities and counties could prevent many traffic deaths by investing in safe streets: clearer signs and signals, more curb extensions and crosswalks, more and better marked bike lanes. Finally, if a city or county has enough transportation sector revenue to meet its maintenance needs, it can free up general taxpayer money for other things, like parks and police.

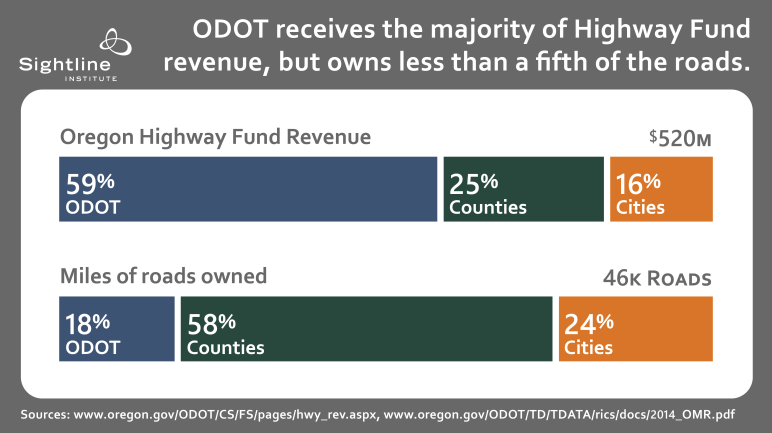

Currently, more than half of the $520 million Highway Fund goes to ODOT, about a quarter to counties, and the remainder to cities. This division of revenue is almost a complete inversion of the miles of road each entity pays to maintain: Counties own and maintain more than half of the roads in Oregon, cities about a quarter, and ODOT less than one-fifth. (Roads maintained by the US Forest Service, the Bureau of Land Management, and private entities are not included in this graph.) A cap on pollution will grow the Highway Fund pie, but if Oregon maintains the current division of funds, ODOT will receive most of the benefit.

Original Sightline Institute graphic, based on data by Oregon Department of Transportation, available under our free use policy.

As part of a pollution bill, the legislature could change these percentages to give local communities a fairer share of the funds, enhancing local maintenance budgets, filling potholes, and creating local jobs. Alternatively, the legislature could put all the pollution revenue in a subaccount of the Highway Fund and dedicate the subaccount exclusively to local maintenance. Cities, counties, and all their street maintenance contractors would happily lobby the legislature for a bill that sends $300 million their way, creating unexpected allies for climate activists.

A more distant solution: Amend the Oregon Constitution

It would make most sense to use pollution revenue from the transportation sector to invest in infrastructure that helps Oregonians get around without polluting. Oregon could expand transit options, add electric vehicle charging stations around the state, and build paths to make it safer for people to walk and bike in their communities. But first Oregon would have to legalize such a common-sense option by re-amending its constitution (a 1980 ballot initiative amended the constitution to add the current limitations on gas tax revenue).

Voters can amend the Oregon Constitution via direct petition or by approving a legislative referral to the ballot. And indeed, legislators and activists have made several runs at amending the Oregon Constitution to broaden the use of Highway Funds: in 2000, Measure 80 would have allowed funds to be used for increased highway policing; in 2013 and 2015, Representative Jules Bailey and Senator Michael Dembrow (respectively) introduced resolutions to allow funds to be used on projects that would help people get around by bus, bike, and foot. These efforts failed, but a Highway Fund bloated with polluter-pay revenue might provide the fateful spark.

Onward!

Oregon has a chance this year to cap climate pollution. If environmental, local, and public transportation advocates play their cards right, the resulting revenue could solve a major funding problem for local communities, save lives on safer streets, and create jobs locally. Not to mention boosting the creation of a stable source of funding for safe, low-pollution ways for all Oregonians to get around.

Comments