In a nutshell: regional cap-and-trade programs matter because the threat of disjointed regional action is one of the single biggest drivers of climate policy at the federal level. Though it’s often overlooked, the presence of regional programs is a central reason why the nation’s biggest polluters—and biggest opponents to pricing or capping carbon — are coming to the bargaining table now.

Consider this article from Environment & Energy Daily (subscription only):

The [Waxman-Markey] legislation as written would prohibit states and localities from implementing or enforcing their own caps on greenhouse gas emissions from 2012 through 2017.

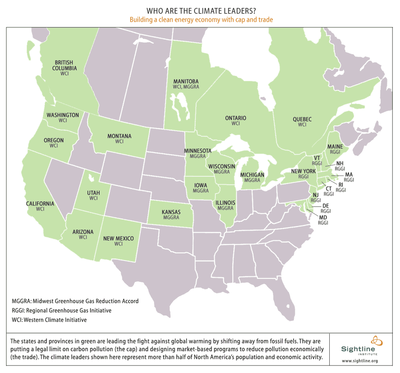

The provision would effectively dissolve state and regional programs like the Northeastern Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative, the Western Climate Initiative and the Midwest Greenhouse Gas Reduction Accord.

Industry groups, however, are hopeful that a federal climate program will eliminate a patchwork of state and regional regulatory programs.

William Kovacs, the U.S. Chamber of Commerce’s vice president for environment, technology and regulatory affairs, told Markey’s panel that the bill should go even further by permanently pre-empting state and regional climate programs.

Not that the bill should promise to eliminate regional programs. But as a negotiating tactic—as a way to bring big polluters to the table—it’s exactly right.

Check out this map of regional cap and trade programs. This gives a fair idea of the fragmented policy world that’s confronting North America’s biggest carbon emigtters.

At this point, more than half of North America’s economy and population is seriously considering cap and trade. (Bigger versions for free download are available here.) It’s no wonder industry would prefer a single policy for the continent. (It’s almost assured, by the way, that Canadian national policy will closely track US policy.)

Plus, if US federal climate policy turns out to be robust, fair, and efficient, then it probably really would be best to have just one unified program rather than many smaller disparate ones. But if regional cap and trade goes away, you can be pretty sure that polluters’ interest in unified federal policy will wane.

Of course, pushing polluters toward federal climate policy is not the only reason why regional programs matter. They matter in their own right because they can set the terms of good (or bad) policy. And if federal action sputters, or if it’s weaker than it should be, regional programs should take up the torch of good policy.

Michael Andersen

Agitating for regional policies that we know are going to be inferior to a similar national policy is an interesting tactic.At one extreme, you’ve got a bad-on-the-merits regional policy that’s easy to pass. Given a limited amount of political capital available to environmentalists, that’d be a waste of effort. At the other extreme, there’s a highly efficient national policy that’s very hard to pass.I suppose there must be a sweet spot in between—a regional policy that’s mediocre but doable, and therefore has the incremental advantages you describe.Also, the interesting implication is that there won’t be much pressure for any worldwide regulatory system (in carbon or any area of economic regulation) until there are many companies who do business in multiple countries.