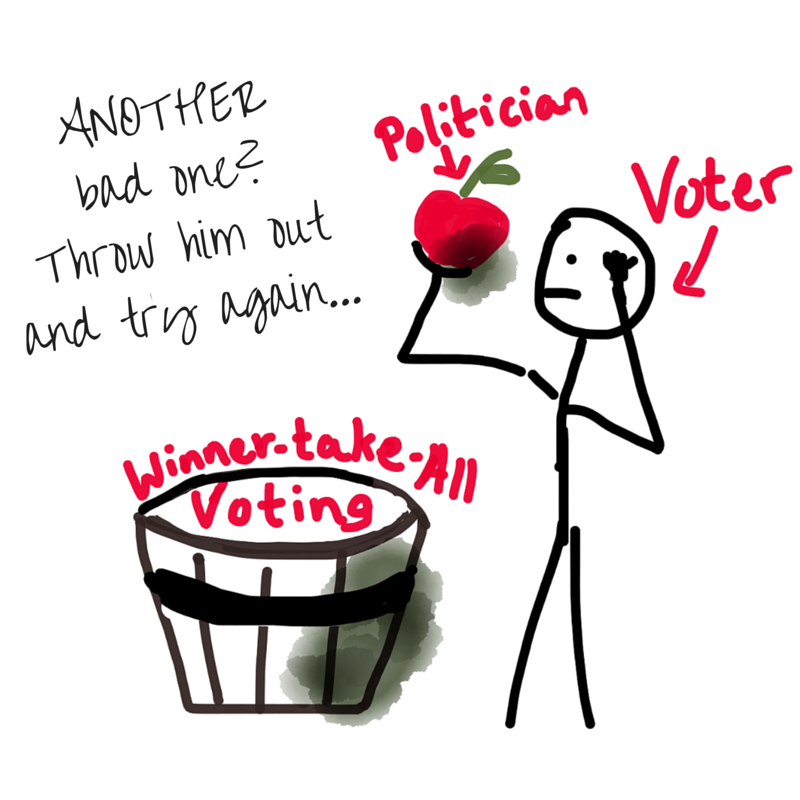

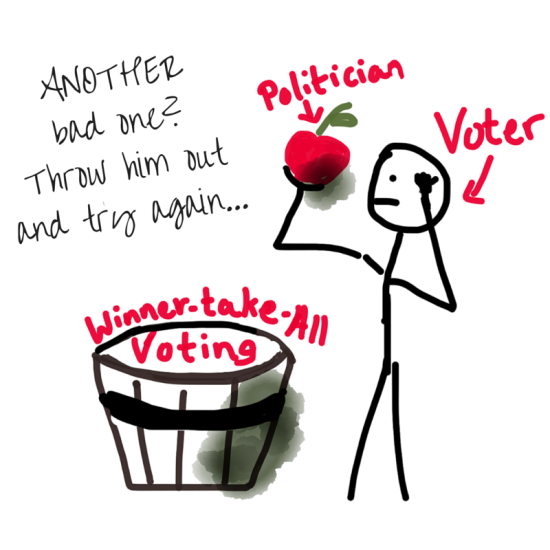

It’s tempting to think of politics in terms of personality problems: if only Obama were warmer, he might be able to break through Congressional gridlock. If only Dino Rossi weren’t such a hard-nose, he wouldn’t inspire such negative campaigns. But with wave after wave of negative campaigns, it seems the problem is not really politicians’ personalities. Maybe all politicians are not bad apples. Maybe our voting system is a bad barrel. The apples are fine when they go in; the barrel itself makes them rot.

In my last article, I explained the problems that winner-take-all voting creates: unrepresentative government that gives short shrift to women, racial minorities, and third parties, and the solution that multi-member districts and ranked-choice voting offers for generating proportional representation in which women, racial minorities, and political minorities have a voice in government proportional to their strength in the populace. In this article, I’ll show that winner-take-all voting spawns negative campaigns. But fair voting—multi-member districts with ranked-choice voting—creates more civil and engaging campaigns.

Problem: Campaigns are negative and divisive.

North Americans have a long history of outrageously negative campaigns, reaching back to 1800 when John Adams’ campaign called Thomas Jefferson a “mean-spirited low-lived fellow, the son of a half-breed Indian squaw, sired by a Virginia mulatto father” all the way to a more recent campaign in which Canada’s Conservative Party opened its home page with an animated puffin defecating on the opposition leader’s shoulder. It isn’t because North Americans are uniquely antagonistic; it is because winner-take-all elections inherently reward negativity.

In a “winner-take-all” or “first-past-the-post” election, one candidate with the most votes wins, so each candidate’s goal is to get more votes than the other guy. The contest for each vote is a zero-sum game: the voter is either with you or against you. As a result, elections are as much (or more) about besmirching the other candidates’ reputations as they are about selling voters your own positive vision. There is no harm in offending your opponents’ supporters because they weren’t going to vote for you anyway. But if you can convince some undecided voters that the other candidate is a foreigner, a Muslim, a mulatto, a criminal, an alcoholic, or a sworn agent of the Pope, no matter how false or divisive the rumor, disgusted voters will turn away from the tarnished candidate and fall right into the arms of the rumor-mongering candidate. Attacking your opponent is a winning strategy in winner-take-all.

A recent Cascadian example: in British Columbia’s 2013 election, New Democratic Party candidate Adrian Dix pledged not to run any negative or personal attack ads against candidate Christy Clark; in contrast, independent groups supporting Clark spent $1 million in character attacks against Dix, and voters perceived the Clark campaign to be the more negative. Clark won the election.

Even if negative ads aren’t successful at convincing voters to vote for the candidate running the ads, they might convince undecided voters not to vote at all, which can work for the negative campaigners. Hostile campaigns can turn out their base supporters while convincing everyone else to stay home. Recent elections show that antipathy to the opposing party is a powerful motivator for partisan voters—particularly Republican voters—to turn out to vote. If a campaign is sufficiently nasty, more moderate voters—including Democrat-leaning voters—will wash their hands of it and not vote at all. The more voters stay home, the fewer voters a candidate has to win over to get elected. Negative campaigns are often a winning strategy.

Solution: Reward positive, inclusive, and informative campaigns.

With proportional representation and ranked-choice voting, the contest for each vote is not a zero-sum game: if a voter ranks Candidate A first, all is not lost for you, Candidate B! The voter could still rank you second. Attacking Candidate A might turn the voter off, causing her to skip you and instead rank Candidate C second. Focusing on the issues you care about—not on bashing—can win you a second-ranked vote.

Indeed, Minneapolis Mayor Betsy Hodges, running in a ranked-choice system, explicitly asked voters who preferred another candidate to make her their second or third choice. (Watch her explain in this video.) The incentive to seek second- and third-place rankings meant she spoke with voters she would have written off in in a winner-take-all race. There would have been no point in continuing to talk to voters who had already selected another candidate as their first choice.

Ranked-choice voting in Oakland allowed Mayor Jean Quan to pursue the same successful strategy. She explained: “We talked to everybody, and if you had a sign for Joe Tuman or Rebecca Kaplan or Don Perata, we wanted their number two.” Winner-take-all voting rewards candidates for alienating some voters; ranked-choice voting rewards candidates for engaging more voters.

Ranked-choice campaigns focus more on positivity and policy issues and less on character attacks and mudslinging. Candidates in ranked-choice races find that they have something to gain by being positive about other candidates and something to lose by being negative. Mike Brennan, who was elected mayor of Portland, Maine, under ranked-choice voting, explained: “You don’t spend a whole lot of time saying things about your opponent that might be construed as being negative because whoever votes for them as number one might vote for you as number two.”

In San Francisco, candidates in ranked-choice elections positively support other candidates, hoping to win second-ranked votes. Candidates in Oakland have also found there is a cost to mudslinging in ranked-choice elections: the fear of losing voters’ second- or third-choice ranking motivated them to put down the mud and pick up the issues. Oakland Mayor Jean Quan “ran a very focused campaign to be the second-place candidate for a lot of [voters]. She never spoke ill of anyone.”

Voters feel the difference in ranked-choice campaigns. Voters in American cities that used ranked-choice voting, such as Minneapolis, Minnesota, and Cambridge, Massachusetts, were one-third more likely to report less negative campaigns, compared with voters in winner-take-all cities. Voters in winner-take-all cities were 70 percent more likely to say campaigns were more negative. Most voters in winner-take-all cities said that candidates criticized each other some or a lot, whereas 81 percent of voters in ranked-choice cities said candidates did not criticize each other much or at all. Across all demographic categories, voters perceive ranked-choice campaigns to be less negative.

Original Sightline Institute graphic, available under our free use policy.

A Better Barrel

Many Cascadians yearn for a more engaging political process, sometimes wishing candidates could just focus on reaching out to voters about the issues, instead of attacking each other. But as long as winner-take-all voting creates zero-sum games, politicians are left little choice but to mudsling. Multi-member districts and ranked-choice voting can create intrinsic incentives for candidates to focus on engaging voters, not smearing other candidates.

Thanks to FairVote for its decades of research on proportional representation and ranked-choice voting. This article relies heavily on that research.

John Gear

Yes, exactly. The voting and counting rules are the unrecognized DNA of our election features, and ours produce a monstrous, ravenous for cash, zero-sum creature perfectly suited to producing a political landscape like World War I Belgium, with competing armies completely locked into defending miles of trenches that became hellish sewers, which were still better than daring to advance and being mowed down by the enemy.

For every thousand hacking at the branches of a problem, only one strikes at the root. You have hit the root cleanly — until we adopt election rules that avoid zero-sum, expecting any improvement in our politics (or our policies, which are determined by our politics) is like expecting the unicorn stampede. Thank you for bringing this important issue to a broader audience.

RDPence

Thanks for the continued good work on the Single Transferable Vote. I’d like to see a thorough report that documents all the US jurisdictions that use the system, particularly those that use it to elect multi-member bodies such as city councils. Cambridge MA used to be the only one of those.

Pierce County used it for, I believe, one election before voters took it out of the county charter. The big problem of course is explaining the new system to voters and why it’s a good thing. Fail that and we risk repeating the Pierce County experience.

Joe

Some of us rather like accountability campaigns where the truth shakes out, instead of letting candidates blather on and on about how great they are. It’s called getting to the truth.

Adrian Dix wanted to kill jobs in BC.

Dino Rossi ran a slick, polished campaign – it was Gregoire who ran a negative campaign and LIED about her plans to raise taxes WITHOUT voter consent.

John Koster – a Republican – would have squeaked by if not for some of the hard muckraking done against him.

Food for thought.

Kristin Eberhard

Thanks for your thoughts, Joe.

I think there is a difference between accountability and mudslinging. John Adams wasn’t aiming to “get to the truth” by calling Jefferson a “mean-spirited low-lived fellow”; showing a puffin defecating on someone’s shoulder isn’t “getting to the truth” of her policy plans. A 30 second TV ad can convey emotionally powerful messages, but not a big dose of truth.

Putting down the mud and picking up the issues means focusing on policy issues over gratuitous negativity. In the campaigns mentioned above, it is not that no one ever criticized other candidate’s policy positions – of course they tried to distinguish their positions for voters – they just focused on policy rather than character attacks.

Joe

Thanks Kristin for clearing it up. I don’t think John Adams had to go after Thomas Jefferson like that.

I think if voters rewarded those who focused on issues instead of emotional appeals we’d all be better off. But that means putting down the video games and sitcoms and tuning into TVW, C-SPAN and political debates again!

Steve

Vote No on I -122 I have found after doing homework that I -122

has parts that have been ruled unconstitutional by the US Supreme

Court. This was poorly written and the campaign against this

will be honest. It covers more than one subject and is written

just like a Tim Eyman I and will be ruled un-constitutional

and if for some god knows the reason it might pass it will cost

the city plenty of money loseing in Court.

Steve

James D'Angelo

This is an insanely important topic and no one has covered it better than Kristin does here. I’ve been working on the statistics and elementary math of this assumption and it is jaw dropping. If we don’t clean this plurality-winner-takes-all mistake up, we will continue to pay the price. Brava Kristin.