March 22 marked the first anniversary of the landslide in Oso, Washington. A water-logged mountain slope gave way, unleashing staggering volumes of earth and debris that swept across a small community and killed 43 people. Oso was an awful lesson in the destructive power of slides.

It’s a lesson that bears special consideration as the Northwest considers proposals to add dozens of hazardous coal and oil trains to coastal rail lines that are routinely plagued by slides.

We know that when oil trains derail they are prone to spills and catastrophic fires, mishaps that would be very challenging to address in many of the remote locations traversed by the main rail route along the northern shores of Puget Sound. Although the dry winter of 2014-15 maintained mostly stable earth along the rail lines, the region is not always so fortunate. During the wetter winter of 2012-13, for example, hillsides collapsed repeatedly over the tracks, forcing officials to cancel 206 passenger trains over 28 days. Prior winters had also yielded meaningful delays due to landslides.

Even if you’re not a north Sound commuter or an Amtrak rider, you may have heard about passengers’ frustration. Or maybe you saw the live video footage of a mudslide that took out a freight train between Seattle and Everett in December 2012.

If that landslide had struck one of the loaded oil trains that now run through that very same spot, the consequences could have been dire.

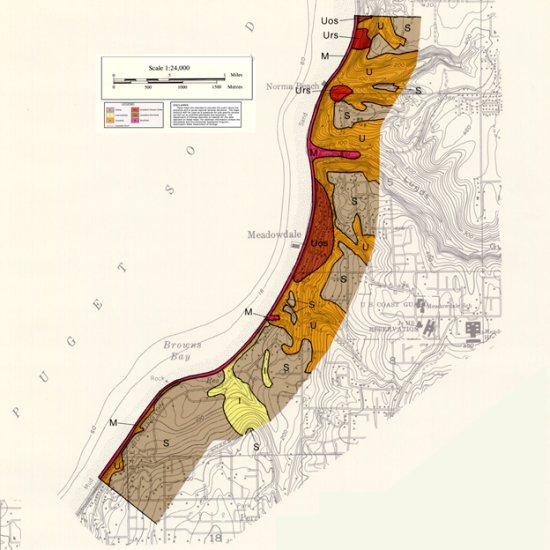

While 2012-13 was one of the worst slide seasons in a hundred years of record keeping, it was really just part of a natural geologic pattern of unstable Puget Sound bluffs eroding down to the beaches—the same beaches that now host the region’s major rail route. When these hills slide, they end up on the tracks more often than not. The Washington Department of Transportation calculates that from 1914 to 2001, more than 900 slides occurred on the slopes north of Seattle—with 80 percent leaving debris on the tracks.

Direct hits are not unheard of. Perhaps the most noteworthy instance of a landslide colliding with a train was in 1997 at Woodway, near Edmonds. A deep slide cut tens of feet into the slope and sent 60 Olympic-size swimming pools worth of earth slamming into a freight train, sweeping five rail cars into Puget Sound. It left debris standing 20 feet high on the tracks. Just hours earlier, an Amtrak passenger train with 650 people aboard had passed by.

The crude-by-rail facilities operating and proposed at northern Puget Sound refineries mean that several loaded oil trains run along those tracks every day.

Landslides share some common features, but it is nearly impossible to predict when they will occur over an entire rail corridor. Complicating matter is the sheer number of potential slide locations. In fact, geologists have identified hundreds of unstable slopes up and down the Puget Sound coastal rail routes.

BNSF spokesman Gus Melonas put it well: “Anytime a 300-mile corridor from Portland to Vancouver, BC, is lined on one side with water, and steep slopes on another, and we’re in the middle of this rain-forest area, slides are a reality.”

Rain is a key risk factor, and Northwest winters may become wetter as the climate changes, but the effects are not regular and they vary based on local conditions, such as drainage, vegetation, and slope gradient. In Woodway, for example, the slide area had not seen heavy rains for a couple weeks prior to the hillside giving way, and a second minor slide occurred the day after the major event. Earthquakes can also trigger landslides, especially when the soil is wet. A recent University of Washington study illustrated this point with historical evidence: the Nisqually earthquake of 2001 set off more than 100 slides. In the the past it was not uncommon for triggering earthquakes to send whole forests sliding into Lake Washington.

If there’s a fix for the landslide prone bluffs along the railway, it’s not an easy one. Washington has received some federal funds for mud control above railroad tracks, but it is essentially a multi-million dollar game of whack-a-mole, and the potential need dwarfs the few projects underway. In the meantime, the railroad continues to haul three-million-gallon oil trains along the route two or three times a day, on average.

After a slide, passenger trains face a railroad-imposed 48-hour waiting period, ostensibly in the name of public safety. Yet that policy does not apply to freight trains, not even those carrying dangerous or explosive cargoes. Former transportation analyst Larry Ehl, now Chief of Staff at the Port of Seattle, recommended that given the severity of the threat, the “safety first” position for passenger service would be to completely shut down for the rainy season. A similar policy would be wise for hazardous cargo like oil.

In the aftermath of the devastating Oso landslide, reporters at the Seattle Times tracked warnings going back decades. It’s all-too-similar to the repeated warnings about Puget Sound bluffs. And if a landslide like the one in Woodway knocks down an oil train or sweeps it into Puget Sound, the damage—whether from fire or spill or both—will be the stuff of unfortunate future headlines.

Comments are closed.