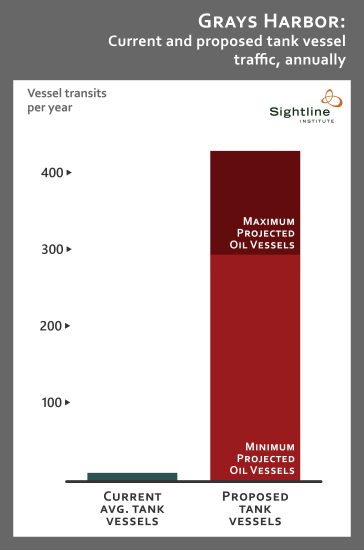

Of all the places in the Northwest that would be affected by a ramp-up in oil transport, none stands to be as profoundly transformed as Grays Harbor. A trio of proposed crude-by-rail-to-vessel schemes at the Port would result in staggering increases in oil-bearing vessels moving in and out of the bay.

Based on figures in the the Washington Department of Ecology’s “Vessel Transit and Entry Counts” database, it is possible to contrast the average volume of ship and barge traffic over the last decade to the number of vessel trips that would be induced by planned oil sites on Grays Harbor. The most direct comparison—the number of current to potential future tank vessel—reveals that the three sites could multiply laden oil tankers and barges by 44 times.

Original Sightline Institute graphic, available under our free use policy.

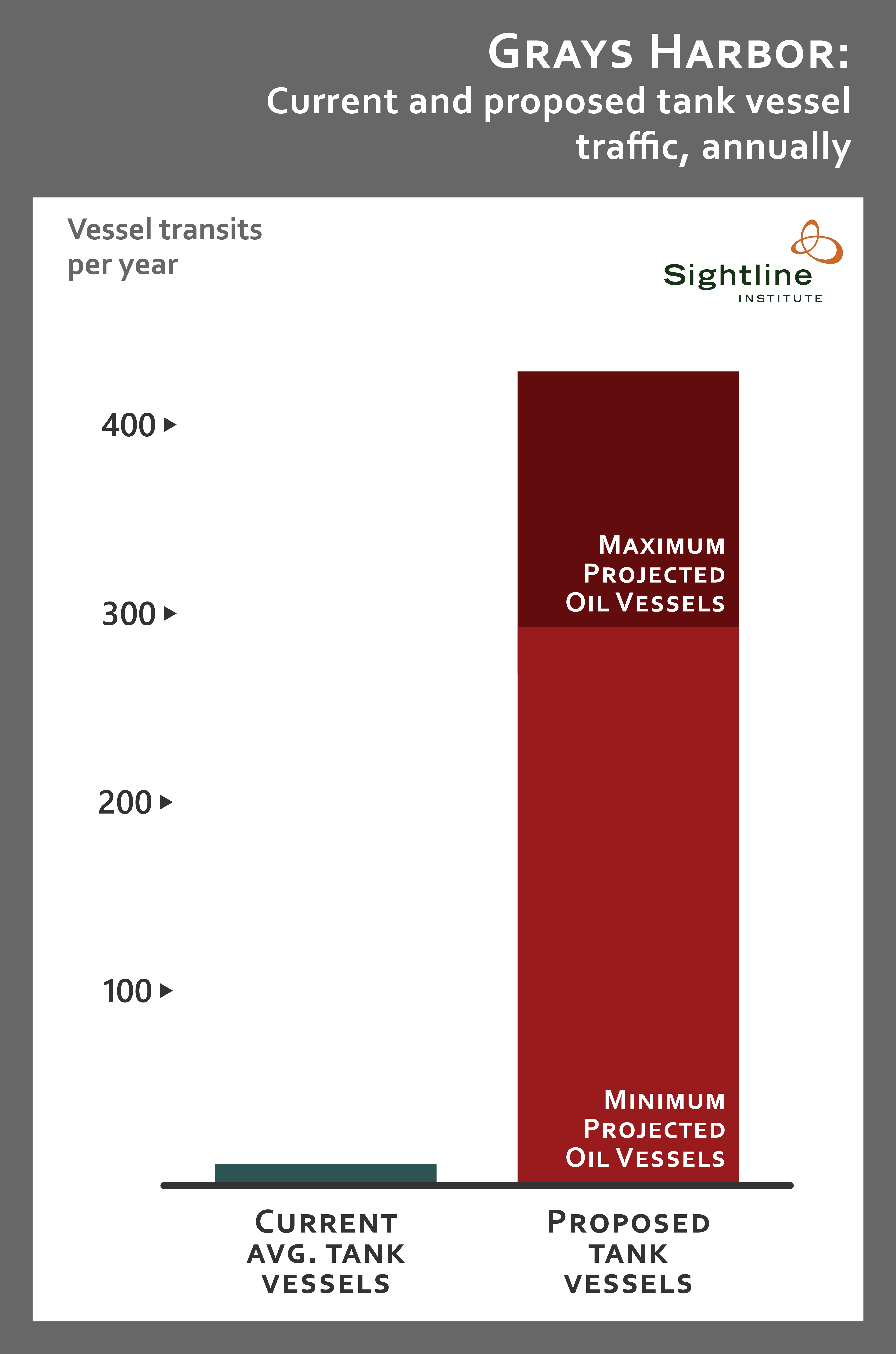

A closer look at ship traffic trends in the harbor reveals that the trips induced by the oil depots would dwarf not only existing tanker and tank barge movements, but all major vessels.

Original Sightline Institute graphic, available under our free use policy.

In fact, the three sites alone could easily increase overall vessel transits in Grays Harbor by more than five times beyond average levels of the past decade. And our estimates are likely too conservative because we do not count ancillary vessel trips induced by these fossil fuel projects, such as the refueling (“bunkering“) vessels that would be required to serve ocean-going cargo ships.

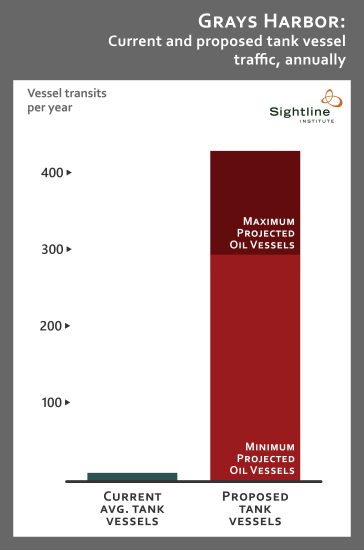

Not only would the plans yield huge increases in tank vessels, but they would dramatically increase the amount of oil stored at shoreline facilities in Grays Harbor.

Original Sightline Institute graphic, available under our free use policy.

Two of the three sites—Westway and the Imperium biodiesel site—already store around one million barrels of fuels and liquids like methanol, biodiesel, and canola oil. Their oil expansion plans, plus those of US Development nearby, would more than triple the amount of storage tank capacity for crude.

For a more complete accounting of fossil fuel vessel traffic serving these oil sites, see the graphic below.

Original Sightline Institute graphic, available under our free use policy.

In previous installments of our vessel traffic analysis, we’ve looked at the potential increase in oil tankers and barges on the Columbia River and in the Salish Sea, both home to invaluable ecological resources that in turn support substantial economic activity. Though less well-known, Grays Harbor is no different.

The 1,500-acre Grays Harbor National Wildlife Refuge hosts huge quantities of migratory birds. In fact, the Grays Harbor ecosystem is designated a site of “Hemispheric Importance” by the Western Hemisphere Shorebird Reserve Network because over 500,000 shorebirds roost and forage in the area annually. And oil vessels calling at Grays Harbor would also jeopardize other natural refuges that are home to endangered species, including the nearby Olympic National Park and Olympic National Marine Sanctuary to the north, as well as the Willapa National Wildlife Refuge to the south.

In addition, the Quinault Nation has call the Grays Harbor home for thousands of years. Culturally and economically reliant on the region’s rivers, estuaries, and saltwater, an unprecedented boom in oil transport would endangered the very foundation of the tribe, even as the plans likely represent an abrogation of the Quinault treaty rights under US law.

Update 3/11/15: Paul Query, spokesperson for the Westway and Imperium projects, provided additional data from the Port of Grays Harbor that show annual vessel calls from 1960 to 2013, a much longer period than is covered by Ecology’s VEAT data that we report here. (The two data sets are roughly consistent for the years they count in common.) During the period from 1960 to 1999—that is, the years prior to the trend line in our chart above—the Port’s data show an average of 220 vessel calls per year with a high of 313 in 1968 and a low of 103 in 1989.

Notes and methods. The data we report here come from the Washington Department of Ecology’s “Vessel Transit and Entry Counts” database that we parsed into three regions: Puget Sound, the Columbia River, and Grays Harbor. Our figures refer to “transits,” which are ship movements, rather than “vessels,” which refer to unique ships. A vessel may make multiple transits in a given year, so estimating vessel traffic is best done using transit numbers. There are, however, some methodological wrinkles in the VEAT data, such as an apparent discrepancy in the way that barges and ships are counted. Barge transits are defined as “any significant move between two locations, via Washington State waters, while transporting oil or chemicals,” while ship transits are defined as “the passage of a vessel from sea or from Canadian waters into Washington waters…the trip back to sea is not counted.” In other words, a movement by a barge (between, say, two ports on the Columbia River) would be counted as a barge transit, while a similar movement by a ship would not be counted as a ship transit. Our estimates of future vessel traffic strive for consistency with VEAT’s method of tracking barge and ship movements.

Data for the Imperium project come from Imperium’s permit documents, here; and Port of Grays Harbor project documents, here.

Data for the Westway project come from Washington Department of Ecology, Determination of Significance, here; and Port of Grays Harbor project documents, here.

Data for the US Development project come from the City of Hoquiam’s SEPA Checklist, here; and US Development FAQs here.

For the three terminals, we also used data in Sightline’s report, “The Northwest’s Pipeline on Rails,” as well as in the Washington Department of Ecology’s report, “2014 Marine and Rail Oil Transportation Study.” We made two estimates for oil from trains: the high estimate assumes that all oil is transported by tank barges carrying 150,000 barrels each. Tank barge capacities can vary widely, from as small as 10,000 to as large as 327,000 barrels;

We estimated that barges would have a capacity of 150,000 barrels per vessel, based on Imperium’s SEPA Checklist, and corroborated by descriptions of the other Grays Harbor proposals. (It seems to be slightly larger than typical tank barge average capacity, so our assumption therefore represents a somewhat conservative account of induced barge traffic.) The low estimate assumes that all oil is transported in Panamax tankers carrying roughly 360,000 barrrels each, a figure that is consistent the throughput volumes and estimated vessel numbers for the Tesoro-Savage proposal at Vancouver, Washington on the Columbia River.

Robert McDonald

As a former News Director at KBKW (back in the day when the station was on the bank of the Wishka River) LOG carriers and CHIP carriers from Aberdeen and Cosmopolis would run aground, right off the pier at Aberdeen.

The Port will require a funding for constant dredging of this mud filled bay. It was like pulling teeth “back in the day” which resulted in the shuttering of Raymond.

The current cast of mis-fits in DC can’t even keep Homeland Security Funded, never mind asking for funds to dredge mud!

David Moore

Seems like the Bakken crude from North Dakota should be saved for current and future US use and not used to endanger the salmon, crab, razor clams, sturgeon and birds of Grays Harbor.Not too long ago US presidents raced into a Middle East war partially over oil supplies. Maybe it should be conserved.

Julia Cochrane

Looking to connect with people organizing around Gray’s Harbor.

Leif Knutsen

Capitalism, unrestrained by the requirements of Planetary life support systems, is guaranteed mutually assured destruction. Socially enabled capitalism is clearly a failed paradigm. Help end tax funded pollution of the commons for starters. If we do that one thing fossils will remain in the ground.

Go GREEN, resistance is fatal to Planetary life support systems.

harryfsher

property tax in grays harbor is extremely high, if the taxes paid by the rail road companies and oil companies would allow the reduction of property tax on our homes. It certainly would increase good paying jobs and perk up the economy and be a boom for small business, and make the harbor be a vital place to live again.