Most Americans—including most Republicans—want to regulate carbon pollution. Oregon and Washington have already set legally binding limits on the climate-changing gas. Next, climate change warriors in Olympia and Salem are trying to make those limits enforceable. They’re considering hard emissions caps enforced through limited permits and complemented by an array of targeted policies.

But what if Oregon and Washington’s lawmakers fail to insert sharp incisors in their beyond-carbon rules? Desperate for revenue to fulfill its McCleary obligations, Washington might pass a modest carbon tax not designed to slash pollution. Oregon might do the same, for its own revenue reasons. Such taxes would nudge the states’ economies toward a clean-energy transition, it’s true, but they would not guarantee that emissions drop to the statutory goals.

And, I shudder to ponder it, but the legislatures might simply refuse to price carbon at all, at least not yet.

In fact, a few state legislators, briefed on the fine points of carbon pricing, have rolled their eyes at the political challenges and said, “Why do we have to price it? Can’t we just regulate it?” Polls suggest some voters would actually prefer direct regulation. The logic is seductive: Polluting is irresponsible behavior. Polluters should knock it off. If they don’t, authorities should make them.

This article describes that scenario: what would it look like if we just make polluters emit less carbon?

Regulating our way to a post-carbon world.

Unfortunately, “just make them” is not an elegant picture. The authorities in charge of “making them” would be state agencies, but clashing jurisdictions, inadequate legal tools, administrative silos, and potentially perverse incentives across economic sectors make a purely regulatory approach to carbon limits a fourth or fifth or tenth best approach. Still, it’d be better than nothing. It would limit pollution, albeit in a splintered and probably costly way. In any event, it’s important to understand the regulatory options, just as I reviewed other imperfect but conceivable paths beyond carbon.

Paradoxically, some of the policies state agencies would implement might be quite effective if implemented as complements to a carbon cap, because they help cut pollution inexpensively and bring other benefits like new jobs or cleaner air. But they would work less well without a price as a backstop. In the absence of a cap (or self-adjusting tax), each agency could only quash pollution if granted authority to write and enforce strong new rules—authority on a scale that legislatures have rarely granted.

Here are three variations on the agencies-in-charge path, which, to make more fun, I’ll describe as if you, Dear Reader, were the entire state legislature of either Oregon or Washington:

1. You (the legislature) make state agencies responsible for hitting their own pollution target.

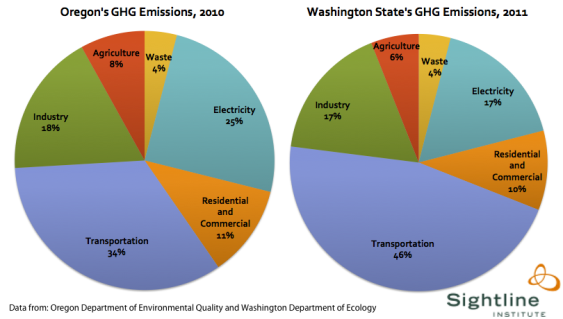

You could write your existing carbon reduction goals into the statutory duties of your agencies. You could set emissions targets for each sector of the economy—transportation, industry, agriculture, utilities, and so on—and then give the appropriate one of your agencies the legal authority to push their sector to its target.

First you would need to pick a pollution number for each sector. The simplest formula would be to require each sector to meet its share of the state’s goals by itself: in Oregon, each sector would have to slash pollution 75 percent below its own 1990 levels by 2050; in Washington, each sector would have to cut pollution 50 percent below 1990 by 2050. If you thought it was unfair to hold each sector to its own 1990 benchmark—maybe because in 1990 Oregon had a nuclear power plant that made that year’s power sector emissions lower than subsequent years—you could instead require each sector to shave some percent below current or forecast emission levels. Or you could set sector pollution limits based on how easy or difficult you think (or you guess? or industry lobbyists tell you?) it will be to move that sector off carbon.

Say you get past that first (difficult) hurdle and choose a number for each sector. Whew. Now you get to pass the buck to the agencies! These are the sectors that generate greenhouse gas (GHG) pollution in Oregon and Washington, and the agencies that you might want to put in charge of each:

- Electricity: Oregon Public Utilities Commission (OPUC) and Washington Utilities and Transportation Commission (WUTC)

- Transportation: Oregon Department of Transportation (ODOT) and Washington State Department of Transportation (WSDOT)

- Industry: Oregon Department of Environmental Quality (ODEQ) and Washington Department of Ecology

- Agriculture: Oregon Department of Agriculture and Washington State Department of Agriculture

- Solid Waste (mostly methane from landfills): Oregon Department of Environmental Quality (ODEQ) and Washington Department of Ecology.

Original Sightline Institute graphic, available under our free use policy.

You would give each agency authority to create new regulations or ramp up existing regulations to make sure it hit the pollution target you set for it. This approach could avoid, for example, the Washington Court of Appeals’ conclusion in Cascade Bike v. Puget Sound Regional Council that the regional planning council was not obligated to reduce carbon pollution. You would make clear that each agency is obligated by law to cut pollution and any agency that fails to do so will have to answer to you and the courts.

Here are some examples of the policies these agencies might enact:

- The Oregon Public Utilities Commission could increase the state’s renewable portfolio standard from 25 percent to 40 percent or more.

- The Washington Utilities and Transportation Commission could require utilities to invest more money in energy efficiency.

- The Oregon Public Utilities Commission could raise the cap on the amount that industrial customers pay towards energy efficiency so that the Energy Trust of Oregon could go after more industrial efficiency projects.

- The Washington Department of Transportation could require the state’s 14 Regional Transportation Planning Organizations and counties engaged in planning to push compact and transit-oriented development.

- The Oregon Department of Transportation could require Oregon’s ten Metropolitan Planning Organizations to prioritize increased walkability, bikability, and transit access.

- The Oregon Department of Agriculture could require dairies to install methane digesters.

- The Washington Department of Ecology could require local governments to recycle 80 percent of the solid waste stream.

Unfortunately, these agencies might be hamstrung by a lack of authority. You would need to delegate enormous power to the agencies or risk failing to make the pollution cuts that are already enshrined in state law. Here are some examples of the policies that agencies might need you to give them more authority for:

- Oregon’s Utilities Commission might need the authority to tighten the state’s emissions performance standard.

- Washington’s Utilities Commission might need the authority to require energy performance disclosures for private buildings.

- The Department of Transportation might need the authority to impose a VMT tax or other way to price pollution from driving and use the revenue to invest in transit options.

- The Department of Transportation might need the authority to impose a carbon fee and fund compact development and transportation projects.

- The Departments of Environmental Quality and Ecology might need authority to implement a product stewardship framework to force manufacturers to take responsibility for their products, cradle-to-grave.

Finally, there are many areas where you would not really be able to hold one agency accountable for a sector’s pollution because there is a mismatch or overlap between agencies and emissions. For example, what authority does the Department of Transportation have over the Regional Planning Organizations? What authority does the Department of Ecology have over local governments’ recycling programs? Here are some examples where the point agency just doesn’t have the power to do what you need them to do:

- Building codes are an important tool for improving energy efficiency, but the utilities agencies don’t oversee them. The Washington State Building Codes Council, advised by the Washington State Department of Commerce, advises the legislature on changes to the building code. The Washington Utilities and Transportation Commission could only request that the Building Codes Council advise the legislature to improve the code. Similarly, in Oregon, the Building Codes Division develops and adopts statewide building codes. In other words, the Commission in charge of meeting pollution goals would only have the power to beg two other government bodies to make needed changes.

- Appliance efficiency standards are another tool for getting cheap clean energy by using less electricity to get the same cold beers out of a more efficient fridge. Many appliance standards are out of state hands because they are regulated by the federal government, but for those appliances left to state jurisdiction, the Oregon Department of Energy and the Washington State Department of Commerce are in charge. If the Oregon Public Utilities Commission and Washington Utilities and Transportation Commission were the agencies responsible for hitting a carbon pollution number, they would have to ask the Energy and Commerce departments for help, but would not have the authority to take action themselves.

- In the transportation sector, the main opportunities for cutting pollution from individuals’ driving (as opposed to trucks moving freight around) are (1) to make cars burn fuel more cleanly, (2) to use cleaner fuels, and (3) to give people better options for getting around without driving as much.

- In the first category, Oregon and Washington have already taken the critical step of passing a Clean Car Law.

- In the second category, Oregon and Washington are contemplating a Clean Fuels standard, but you (the legislature) would need to act. If you instead gave an agency sufficiently broad authority to enact a Clean Fuel Standard if it chose to, the agency you would give this authority to would be ODEQ/Ecology. The Departments of Transportation would be dependent on you and ODEQ/Ecology to properly implement a policy that would help meet their responsibilities.

- The third category requires changes in land-use laws to plan cities around people rather than cars, and funding for transit so people can get around those well-planned cities. A comprehensive state climate package could make the needed changes to land-use planning requirements and dedicate some of the carbon revenue to transit funding. But making the Department of Transportation answer for all transportation GHG pollution in the state is tricky. Land-use planning is under the purview of regional planning bodies and counties and cities, not the state Department of Transportation. You would need to give the Department of Transportation authority over the regional planning bodies (not popular), or make them answer for pollution that they have no control over (not fair).

- The Washington Department of Ecology—not the Department of Agriculture—regulates air emissions from the agriculture sector and also collaborates with agriculture on water. In Washington, you might want to put Ecology in charge of agricultural emissions, rather than putting the State Department of Agriculture in charge but forcing them to ask for Ecology’s help. (The Oregon Department of Agriculture is responsible for air and water pollution, so you would put Ag in charge).

- Agencies from different sectors might even work at cross-purposes. For example, electric vehicles can slash pollution from the transportation sector. But OPUC/WUTC, desperately trying to meet the goals you assigned them, might kneecap any attempts to add electricity demand from electric vehicles.

Many of these policies would work better as part of a state-wide climate strategy that you design, rather than developed helter-skelter by a few agencies trying to rise to the (potentially impossible) task of achieving sector-by-sector pollution targets.

Pros:

- Price certainty of carbon tax, if included.

- Agency accountability for meeting pollution targets.

Cons:

- Difficult for legislature to formulate fair targets for each sector.

- Difficult to give agencies the necessary authority.

- Agencies working in silos could unwittingly work at cross-purposes.

- The agency with the responsibility for meeting the goal will need to ask other agencies for voluntary help.

- Balkanized approach would be less efficient than economy-wide price and could discourage cross-sector technological innovations, like electric vehicles.

2. You authorize agencies to implement climate policies but do not assign specific pollution targets.

If you can’t pass a statewide cap or tax or sector-based pollution targets (sob) you might fall back on sector-based policies and hope those are enough. Like the scenario above, you would pass a bill requiring all state agencies to reduce GHG pollution to meet the state’s climate goals, but you would not set enforceable targets for each sector. This would be like California’s program, but without the cap to ensure the state actually reduces pollution. The agencies would need to develop and enforce policies designed to move their sectors toward a clean, low-carbon future, but they would not be required to reach a certain pollution target. The big disadvantage of this approach relative to the one above is that, if the state failed to meet its statutory targets, there would be no one to answer for that failure. Not you, not the agencies. There would just be a big state-wide shrug. An important advantage is that you would not be limited to putting a single agency in charge of the entire sector, so you could avoid some of the inter-agency awkwardness described above. Your bill could call out all the relevant agencies mentioned above and ask them to implement whatever policies are within their power to move the state towards its GHG targets.

Pros:

- Agencies would have authority to implement climate policies.

- The legislature could tap multiple agencies to work towards climate goals.

Cons:

- Agencies would not be accountable for meeting pollution targets.

- Difficult to give agencies the necessary authority.

- Agencies working in silos could unwittingly work at cross-purposes.

- Balkanized approach would be less efficient than economy-wide price and could discourage cross-sector solutions, like electric vehicles.

3. One agency to rule them all: you put DEQ/Ecology in charge.

Instead of setting sector-by-sector targets and picking a (possibly impotent) agency to put in charge of each sector, you could put one agency in charge of everything. In Oregon that would be the Department of Environmental Quality, and in Washington the Department of Ecology. Your bill would shift the burden onto ODEQ/Ecology to figure it all out, and give them the authority to order other agencies to toe the line. This would avoid the problem of not being able to pick a single agency for each sector, and would also make someone—namely, ODEQ and Ecology—responsible for getting the state to its climate goals. But other agencies might not appreciate being ordered around by ODEQ/Ecology, and ODEQ/Ecology would not have the in-house capacity and expertise to formulate all the needed policies.

Pros:

- Agency accountability for meeting pollution targets.

- ODEQ/Ecology could try to orchestrate a more coordinated state-wide effort.

Cons:

- Legislature would have to delegate enormous powers to ODEQ/Ecology.

- ODEQ/Ecology would have to order other agencies around.

- ODEQ/Ecology would not have the capacity to do everything needed to get the state to its goals.

Maybe regulating our way is not the best way.

Many of the policies described above are important pieces of the climate puzzle for Oregon and Washington. But they work best when they fit together. You (the legislature) are in the best position to put together the whole picture. A statewide cap or bumpered tax would make polluters—not state agencies—ultimately responsible for pollution cuts, and an accompanying comprehensive package of policies, coordinated across agencies, would capture low-cost carbon-cutting opportunities. But shifting the onus away from polluters and onto state agencies could create a difficult morass of conflicting motivations and could result in perverse results, like the Public Utilities Commissions fighting against electric vehicles. Asking agencies to cut pollution is better than not cutting pollution at all, but it is not the best option—not by a long shot!—for Oregon and Washington to meet their statutory GHG obligations.

Bill Harris

Carbon tax is super good idea because it permits business to make decisions on basis of usual commercial occurrences–in this way has a definite market-related flexibility–and because the tax collected or some part of it can be used to distribute to lower income taxpayers to buffer the nasty rise in cost of living which is likely to happen–payment inversely related to income and recognizing family size.

jerome parker

Excellent overview of the problems of regulation v. tax. However, a critical flaw in the regulatory alternative appears to be absent: the very high potential for political corruption in the awarding of carbon quotas. Can you imagine Boeing or Amazon not getting special consideration?

Troy

That’s a lot of effort to construct an incredibly ridiculous straw-man of a policy and then tear it down. What a uniquely American urge to regulate government rather than polluters…

Your piece does raise an important point though. If carbon pricing is implemented there are a plethora of 4th and 5th best policies that have been implemented that will no longer have any justification and will need to be torn down and many bureaucratic functionaries put out of work.