The BC recipe for carbon pricing looks something like this: Take a carbon tax and mix it with corporate and personal income tax reductions; keep it simple; slowly shift the tax burden from income to carbon pollution over time.

Is Oregon the next place this dish will show up on the menu? Governor Kitzhaber is running for re-election on a platform that prominently includes tax reform. “It’s got to be on the agenda,” he told state business and labor leaders, “and it’s my intention to put it squarely on the table.” Kitzhaber has not yet committed to proposing a carbon tax, but he’s considering it.

Last year, the legislature in Salem passed a study bill specifically focused on “the feasibility of imposing [a fee or tax on greenhouse gas emissions] as a new revenue option that would augment or replace portions of existing revenues.”

The study itself will not be completed until November, but the state has awarded the contract to Northwest Economic Research Center (NERC), headed by Portland State University economics department chair Tom Potiowsky, who previously spent a decade as the Oregon state economist. NERC has already conducted a preliminary report on carbon pricing in Oregon.

The key takeaway from that report was that environmental tax reform can benefit the economy and reduce emissions. “The report shows that putting a price on carbon in Oregon can result in reductions in harmful emissions and have positive impacts on the economy,” it says. Elsewhere, it notes, “[A] BC-style carbon tax and shift could generate a significant amount of revenue and reduce tax distortions while creating new jobs and reducing carbon emissions. The specifics of the tax shift program are key to ensure equitable distribution of costs and benefits, as well as preserve the strength of the price signal.”

Here are some targets to keep an eye on as the state moves forward:

Carbon tax rate

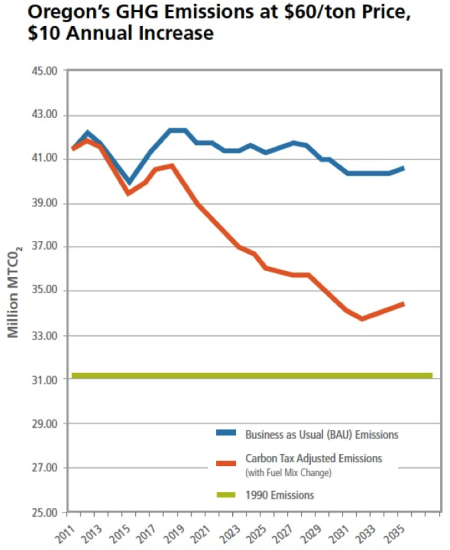

The BC carbon tax started at $10 per ton of CO2 and went up by $5 per ton per year until 2012, when it stabilized at $30. Oregon should at a minimum aim to catch up with BC, and ideally Oregon would enhance revenue stability by indexing the top rate to something like state GDP growth plus 2 percent. (The extra 2 percent would account for and promote carbon reductions.) A tax that rises to $60 would go a long way toward returning Oregon’s emissions to 1990 levels, according to NERC’s projections (see chart). (UPDATE, 4/4/2014: For clarification, the chart shows projections assuming a carbon tax that starts at $10/ton and rises by $10 per year until it reaches $60 per ton.)

Image by Northwest Economic Research Center (Used with permission.)

Carbon tax coverage

Like BC, Oregon would do well to cover all fossil fuels burned in the state. In fact, Oregon could best British Columbia by taxing imported electricity based on the carbon pollution its generation entails. Oregon imports a lot of fossil-fuel-fired electricity from outside of the state; accounting for so-called “carbon by wire” more than doubles the carbon footprint associated with electricity use in Oregon. If you ignore carbon by wire, electric power plants emit about one-fifth of the state’s total carbon pollution; if you include it, the electric sector accounts for almost one-third of the total. The state could also leapfrog British Columbia by taxing the carbon used in airplanes (and perhaps ships) that travel outside the state. Like the province, Oregon can keep exemptions minimal, to ensure fairness and simplicity.

Revenue recycling

NERC estimates that a BC-style carbon tax of $30 per ton of CO2 would generate about $1.2 billion a year, or about 8 percent of the state’s annual General Fund revenue. Taxing carbon-by-wire and jet fuel carbon pollution would boost those numbers to around $1.4 billion and 10 percent. What happens with that revenue is key to the economic and political viability of a carbon tax proposal. (It’s perhaps worth noting that a carbon cap with similarly broad coverage and auctioned permits could generate comparable revenue. The two options are far more similar than many partisans of one or the other care to recognize.)

A revenue-neutral approach—one that devotes 100 percent of the revenue to reducing existing taxes, as in British Columbia—is attractive both for its potential bipartisan appeal and its simplicity. It would also put a political ratchet on the carbon tax: backsliding would be difficult because reversing a carbon tax shift would require raising income tax rates, or other tax rates, that carbon revenue had replaced.

Arguments for dispensing with revenue neutrality also have merit. One of the recommended NERC scenarios, for example, devotes 50 percent of the revenue to corporate income tax cuts, 25 percent to personal income tax cuts, and 25 percent to targeted reinvestments in home energy efficiency, industrial energy efficiency, and transportation infrastructure. Oregon schools are also famously starved for funding, so perhaps a share of carbon tax funds could go to the education budget. These options sounds easy, but the devil is in the details. What if “transportation infrastructure” includes urban highway megaprojects?

Impacts on low-income households

A glance at household energy expenditures for different income quintiles (see figure) shows the importance of addressing impacts on low-income households. Low-income Oregonians devote more than five times as much of their money to energy bills as do the richest Oregonians.

Image by Northwest Economic Research Center (Used with permission.)

NERC notes that “careful program design can also offset the potential extra burden on low-income households,” which is certainly true. Figuring out good ways to do it is a challenge, though. Some options include boosting the state’s Earned Income Tax Credit (currently a meager 6 percent of the federal EITC) or otherwise working through the state’s income tax, providing additional funding for the state’s Low Income Home Energy Assistance Program, attempting to mirror the efforts of programs like Efficiency Maine, or providing a simple dividend to low-income households. (Everything Sightline has written about making cap-and-trade fair for working families applies to carbon taxes, too.)

Impacts on manufacturers and agriculture

Most businesses will hardly notice a carbon tax swap, especially if corporate income tax reductions are part of the package. But energy-intensive businesses (see the list in this paper) might need special attention, especially if they sell into national or global markets and so will be competing with other companies who won’t have to pay the carbon tax. These sectors might be targets for corporate tax relief. The forthcoming NERC study will, we hope, use both case studies and an economy-wide analysis to highlight whether and how a carbon tax could work for these sectors.

Geographic disparities

Northwest politics often divide between the areas west and east of the Cascades, but electricity politics are an order of magnitude more complicated. The map below shows how utility service zones in Portland and surrounding areas are fragmented between public entities (in tan, green, and yellow, representing Public Utility Districts, co-ops, and municipalities, respectively) and Investor-Owned Utilities (IOUs) such as Portland General Electric (orange lines) and Pacific Power (purple stripes). The whole state is similarly balkanized.

Energy Services Map (detail) by Utilities and Transportation Commission

This utility map shapes electricity politics, because different providers cast different carbon shadows. About 30 percent of the electricity in Oregon flows to consumers from Tillamook PUD and other consumer-owned utilities that draw their kilowatts mostly from the Bonneville Power Administration. BPA markets electricity from federal dams and from a nuclear plant on the Hanford Reservation in central Washington. These utilities will not feel much heat from a carbon tax. The rest of the electricity comes from IOUs such as Portland General Electric, which serves 800,000 customers in and around Salem and Portland, and Pacific Power, which serves 550,000 customers, including those in parts of Portland and in some or all of Bend, Medford, and Pendleton. Electricity from these IOUs is much more carbon-intensive, so a carbon tax will hit their customers much harder, especially if it applies to imported electricity. Pacific Power, for example, generates about 65 percent of its juice by burning coal at plants spread across ten Western states.

A tasty challenge

Overall, Oregon is positioned to follow BC’s lead in putting a price on carbon. Yes, there are challenges, most of which British Columbia encountered as well. There’s also opportunity. The preliminary NERC report shows how a carbon tax might be just the recipe Oregon needs: it could provide tax reform and climate solutions in a single dish.

This Thursday, April 3, see Yoram discuss carbon pricing in greater depth as part of a panel at Portland State University’s Institute for Economics and the Environment. Should Oregon Lead on Carbon Taxes? will be held at the Market Center Building, Room 123, and is open to the public. More info is available here.

Kevin

Sounds promising but ow does this square with Article IX, Section 3a of the state constitution. This is the voter approved element that directs revenues from “(a) Any tax levied on, with respect to, or measured by the storage, withdrawal, use, sale, distribution, importation or receipt of motor vehicle fuel or any other product used for the propulsion of motor vehicles; and (b) Any tax or excise levied on the ownership, operation or use of motor vehicles” to the highway fund. The imposition of a carbon tax has salutary benefits on the front end but the full economic value of the tax also comes from how the collected revenue is spent. If the increased carbon revenue only goes to highway construction, it becomes much less attractive as an environmental/economic tool.

I support a carbon tax, and maybe I am missing the point, but I have not seen any discussion anywhere about how the implementation of a carbon tax in Oregon avoids the Article IX conundrum.

Alan Durning

Great question. We think that a carbon tax will pass muster, insofar as it would not be levied on motor fuels per se. It would be levied on all fossil fuels in proportion to their carbon content, probably at the first point of possession in the state.

The Washington state constitution has a similar restriction, but the Washington supreme court recently ruled that a tax that covers a broader category of goods or activities (including but not limited to motor fuels) is not a motor fuels tax restricted to the highway fund.

So, for example, if the retail sales tax covered gasoline, those funds would flow to the general fund, not to the highway fund. Under this principle, if Oregon imposed a retail sales tax, the revenue from gasoline sales would not be restricted to the highway fund. Just so, a carbon tax would cover motor fuels and all other carbon-based fuels.

I’m not an attorney, and I’m no expert on Oregon’s constitution and legal precedents. But the state courts do not operate in a vacuum. A carbon tax properly passed by the legislature or voters might well be challenged by its opponents. But I believe a proper legal defense would prevail in court.

The court would otherwise have to believe that the intent of the section of the constitution that you cite was to siphon all tax revenue even remotely related to motor fuels to the highway fund. And the state does not direct other motor-fuel-related taxes, such as state corporate income and property taxes collected from oil companies and gasoline stations, to the highway fund.

barry saxifrage

Good article. Sightline has been long been a leader in the tax shift idea.

I think it is just a matter of time before simple carbon fees becomes the main tool to fight climate change. So many reasons for this but the two biggest in my mind are because it is so transparent and because it is favoured by most big biz and conservatives. Without these groups joining in it won’t happen.

Exxon prefers a carbon fee. BP just called for a North America carbon fee. BC’s version was created by a fiscal conservative as a billion dollar “income tax cut” that was funded by a carbon fee. And the only proposals I ever hear from conservatives are all simple carbon fees.

Another interesting data point for carbon pricing geeks is that the only scenario the US EIA has that comes anywhere close to cutting USA emissions long term is the one with a carbon fee that starts at $25 and rises 5% per year. All 21 scenarios without a carbon fee lead to USA emissions consistent with IEA’s +6C scenario. I wrote about this just the other day.

The sooner an area starts a carbon fee the lower it can be to start and the slower it will be able to rise. All good things for an economy over the long term. Amazing that no other regions have adopted the BC model yet.

Alan Durning

Great points. Thanks for your comment and work.

Ruth Duemler

When San Diego County Air Pollution with the help of the Clean Air Coalition established an emission fee on heavy industry the next ten years saw an 80% + reduction in emissions. The 2009 Annual Report “Air Quality in San Diego” of the San Diego Air Pollution Control District shows charts and information.