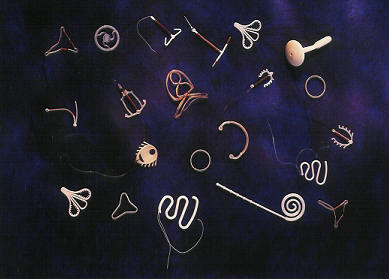

Picture a series of copper beads on a fine titanium alloy wire curved in a graceful sphere. It looks like an earring, but you won’t find it in a jewelry store. It’s made to go in your uterus.

Intrauterine contraceptives are the fastest growing method of birth control in the US. One study showed that use doubled in just two years. Why are IUDs suddenly hot among young women? And what should you tell your friend or daughter when she says she wants one?

Stones in Camels?

Photo by Neil & Kathy Carey, cc.

The idea of putting something small in the uterus to prevent pregnancy goes way back. When nomadic traders needed to keep a female camel from getting pregnant during long treks across the desert, they put stones into the animal’s uterus. Or so the story goes. When Arab gynecologists hear Europeans repeating this tale, they snort and ask, “Have you ever tried to put a stone in a camel’s uterus?” Since the time that a sun-beaten trader might have contemplated camel contraception, intrauterine birth control has come a long way.

Silver and Gold Pessaries

The ancient Greek father of medicine, Hippocrates, is credited with first suggesting small objects in the human uterus to prevent pregnancy. But such a practice would not become common for another two millennia. The precursors of modern IUDs emerged in the late 19th century in the form of “stem pessaries.” The pessary was a curved disk that fit the upper part of the vagina like a cervical cap with the “stem” passing through the cervix to hold it in place. The most elegant designs were made of 14 karat gold and finely crafted, but in the absence of flexible materials, antibiotics, and sterile technique, women who used pessaries risked injury and infection.

Silk Thread, G-spots, and War

By the 1930s, pessaries had been replaced by devices that fit entirely in the uterus. Silk thread wrapped with silver wire was one alternative. Unfortunately, two of the leading innovators, Drs. Ernst Gräfenberg and Tenrei Ota, were German and Japanese respectively, and—although Gräfenberg is immortalized via the “G” spot, which bears his initial––their contraceptive efforts were derailed by World War II.

Flexible Plastics

Lippes Loop IUD. Photo by Washington Area Spark, cc.

As plastics emerged after the war, it was only natural that the new materials were incorporated into contraceptive design. The most popular all-plastic IUD was the Lippes Loop, a sinuous length that curved back and forth in the uterus. The flexibility and shape-memory of plastic allowed a leap forward in terms of safety, but plastic alone provided poor birth control.

Copper Ions as Sperm Zappers

Then, in 1969, a Chilean doctor, Jaime Zipper, discovered the magic of copper. Copper was already known to keep plant diseases like apple rust or peach blight from reproducing. Zipper found that copper also disables sperm. Researchers wrapped a plastic IUD with copper wire so that a few ions at a time could dissolve. Copper boosted the efficacy of IUDs above 99 percent. Things were looking up!

The Dalkon Shield Disaster

Dalkon Shield. Photo by Laura Erickson, used with permission.

And then—in the US at least—disaster struck in the form of an IUD resembling an oversized bacterium. Perhaps, in hindsight, that should have been a sign. The Dalkon Shield, had little feet protruding out on the sides to keep it from being expelled. Great in concept, but the feet sometimes dug in and stuck. For removal, a super strong multifilament string was added, which turned out to be a highway for germs. Most of the 2.8 million users were fine, but others decidedly were not. Some suffered serious pelvic infections and lost their fertility. A handful died.

Women were traumatized. Doctors were traumatized. The FDA was traumatized. And intrauterine contraception largely disappeared from the US market.

Simpler Shape

Paragard IUD. Photo by Mara, cc.

By 1995 only 1 percent of American women used IUDs. In the meantime, intrauterine contraception continued to gain ground in Europe, and over time designs emerged that were effective, durable, and vastly safer than pregnancy. A small plastic T wrapped in copper became the international gold standard. It is twenty times more effective than the Pill, is hormone free, and lasts up to two decades, making it the cheapest contraception as well as one of the best, even today. Fertility returns to normal almost immediately after removal. Most of those 160 million IUD users globally have a variation of this product.

But this technology still has drawbacks. The T doesn’t fit every womb. More significantly, menstrual flow and cramps tend to increase over the first six months before gradually returning to pre-insertion levels, so copper isn’t a good option for women with problem periods.

A Cure for Miserable Monthlies

In the 1970s, researchers tackled the cramping and bleeding problem. Instead of copper ions, the new design released a micro-dose of progestin. Hormonal IUDs decrease cramps and bleeding by, on average, 90 percent. They can be used to treat endometriosis, allowing some women to avoid hysterectomies, and recent research suggests that they even lower the risk of some cancers. Oh, and the pregnancy rate drops below 1 in 700.

Wary American regulators watched the trends in Europe for over a decade before giving their thumbs up. In 2000, they gave approval only for monogamous women who already had babies. Finally in 2012, 20 years after sales began in Finland, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommended IUDs even for teens. No contraceptive fits everyone. But, modern intrauterine contraceptives are now considered safer for healthy women than any other birth control method—or, given the risks of pregnancy, none at all.

This round of innovation has gotten American doctors and women to take a fresh look at intrauterine contraception. Ironically, as hormonal IUDs have gained popularity they have driven renewed interest in the older copper models, especially among women who worry about weight gain or manufactured hormones.

The peak of the surge is among young women who like the idea of lighter, less frequent periods. In an age where women work and work out, get skin tattooed and get body hair removed, deciding how often to have a period seems like part of living a chosen life. Fortunately, the best evidence suggests that our ancestors had fewer periods than modern women and from a health standpoint, less menstruation is better. “When would you like to have a child?” ask family planning doctors. “What would you like to do before then?” And, “How often do you want to have your period?” Based on the answers, they recommend contraceptives that fit.

We have traveled far from the dusty days of stones and camels.

Ocon Med IUB 300. Photo courtesy of Ocon Medical Ltd, used with permission.

What comes next? Increasingly, IUDs and other kinds of medical implants are thought of as future platforms for delivering medications or even personal enhancements. A uterus is a hidden pocket that can stretch to hold a baby, but it also can hold something much smaller. The makers of the lithe sphere described at the opening of this article envision their “Intrauterine Ball” as a means to slow-release not only copper ions or hormones, but potentially other medications that help to treat chronic conditions. A “frameless” IUD, made in Belgium, is seen by its designer as having similar potential. An IUD in China gives off small amounts of indomethacin, an anti-inflammatory. Imagine an IUD that suppressed those monthly chocolate cravings. Now that would be a jewel!

Valerie Tarico, Ph.D., Sightline fellow, is a psychologist and writer in Seattle. She is the author of Trusting Doubt and Deas and Other Imaginings and the founder of WisdomCommons.org. Her articles can be found at Awaypoint.Wordpress.com.

Camilla Mortensen

Given the current use of a smooth, round marble in the uterus to prevent estrus and pregnancy in horses, the camel legend is actually quite possible. Vets have been using the marble technique for about 10 years now. http://www.thehorse.com/articles/13697/marbles-keep-mares-out-of-heat